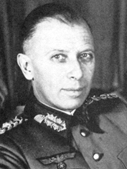

(1897–1982)

A lieutenant in World War I, Heusinger would become a lieutenant general in World War II, serving the German High Command as chief of the Operations Section. He was suspected in the 1944 plot to kill Hitler. Though never tried, Heusinger had reason to believe that the SS (Schutzstaffel) would try to kill him. At the end of the war, Heusinger surrendered to American authorities. He was questioned by U. S. Army Intelligence about many aspects of the war. His candid opinions offer remarkable insights into the German military mind at key points in the war. His military career was capped with his work for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

#

In 1939 Hitler assured Brauchitsch [q. v.] that England and France would not declare war when Germany moved against Poland. The general staff expected a war of two or three months’ duration. After France and England declared war, the opinion was that it would last a long time, but no definite time was predicted. Both Brauchitsch and the chief of the general staff had grave doubts as to Germany’s ability to conduct a prolonged struggle.

In the general planning it was estimated that we would require a four months’ reserve of armaments and munitions to carry through the period of conversion to war production. At the outbreak of the war, however, we had only a two months’ reserve. This gap was bridged during the inactive period of the war between the Polish and western campaigns. (Interview, Military Intelligence Center, Oberursel, Germany, September 12, 1945; obtained through the National Archives; cited in Operation Valkyrie, by Pierre Galante with Eugene Silianoff.)

#

The general staff was of the opinion that a French attack in the west [during the Sudeten crisis of 1938] would have broken through, as our fortifications were not complete, nor were they in 1939, when the French could have broken through, although at heavier cost. The West Wall was completed only from Trier south to the Rhine in 1939. Northward it was incomplete and without any depth. After 1940 construction ceased. To a certain extent the West Wall was a bluff, like the Atlantic Wall. With regard to the latter it was impossible to fortify the entire coast and every military man must have concluded that a landing and a penetration of five kilometers would end all difficulties as far as fortifications were concerned. (Ibid.).

In professional circles [prior to 1939] the following were the most highly regarded [in the German army]: Beck, Halder, Manstein, Heinrich Stulpnagel, Fritzsche, and Brauchitsch. Also Rundstedt, although he was not as active in the War Ministry. General Beck was undoubtedly the greatest spirit in the general staff. However, he was always of the opinion that war would be a catastrophe and in this opinion he found a great friend in General Gamelin. In the general staff we always said that General Halder and General Manstein had received “the necessary two drops of the wisdom of Solomon.” In the top level of the general staff, Manstein was regarded as the ablest and most original planner. That is also my opinion. However, there was no Schlieffen. (Ibid.)

The first plan for an offensive campaign [in the West] was formulated in November 1939. In substance it was a repetition of the 1914 Schlieffen plan. As the start of the campaign was delayed, doubts arose as to the achievement of any surprise with this plan. The basic idea of the new plan-the breakthrough in the Ardennes, crossing of the Meuse, and the trapping of British, French and Belgian forces in the north by pushing the tank forces through to the Channel- came to several minds at once. And in justice it should be said that one of these was Hitler’s. However, General Manstein, then chief of staff to Marshal Rundstedt, deserves the greater credit. He worked out the plan and proposed its adoption. The order was given to the Operations Division in February 1940 to replan the campaign along the proposed lines. From February 1940 to May 1940 the plan was subject to the sharpest criticism. Among the critics was General Guderian, who described the plan as a “crime against Panzers.” General Halder deserves the credit for defending the plan against all critics and insisting upon its execution. General Bock was also opposed to it and appealed to the chief of the general staff. Halder said once that he would stick to the plan if the chances of succeeding were only ten percent. (Ibid.).

#

[The German general staff was] very well informed [of British defenses after Dunkirk]. All equipment of the expeditionary force was lost, and we knew that there were few reserves of men and materiel in the homeland. Never in modern times had Britain been in a more critical situation. Only a man like Winston Churchill could have brought the country through such a crisis. We had no plans for an invasion and no equipment and specially trained forces with which to undertake the invasion. Hence the delay, the hesitation, and finally Hitler’s decision not to risk it. Whether we should have risked it is of course now only a matter of historical interest. Admiral Wagner, with whom I have discussed this question recently and who was then chief of Naval Operations, is of the opinion that it would have failed. I think it could have been done. Militarily, this was for us one of the lost opportunities of the war.

With regard to the air attack in August and September [1940]-the Battle of Britain-I can speak only from the standpoint of the army. It was not thought possible to conquer Britain from the air. The objective was to destroy British air power and gain control of the air. This failed. English aircraft were greater in number than estimated or Britain’s production was higher than estimated. By the middle of September it was obvious that the attack against London would not be decisive. Our losses in aircraft from improved flank and other defense measures became too high in proportion to results achieved. The air attacks were then switched to new objectives-the production and armament plants became targets with a view of knocking out or delaying British rearmament. But in my opinion these were only substitute objectives fixed after the failure to achieve the first main objective-to destroy the British air power and gain control of the air over London and the south coast. (Ibid.)

#

[The original timetable for the Russian invasion] called for the launching of the campaign in May [1941], with the objectives to be reached in five months-that is, in October. But the campaign did not begin until late June, bringing the terminal date into November. Originally, Hitler, the C[ommander] in C[hief], and the chief of the general staff agreed that wherever they stood in November, they would close down operations. However, they gambled with the weather, which in the late autumn was favorable, just as it was to Napoleon in 1812, and kept saying, “We can risk it.” Then came the bitter weather, and the German armies started to retreat.

As far as winter preparations were concerned, measures had been taken by the supply services, but they were inadequate. Clothing was prepared for a hard German winter, but it was inadequate for a severe Russian winter. The transport failed because German locomotives were not equipped for extremely low temperatures. Moreover the Russians in their retreat destroyed all the water tanks and this created enormous difficulties in train operations. The campaign should have been halted earlier and necessary measures taken to hold the positions already taken.

When the German armies began to retreat, Hitler dismissed Brauchitsch and personally took command. He always maintained thereafter that he personally saved the German army from the fate that had overtaken Napoleon’s forces in the retreat from Moscow. (Ibid.)