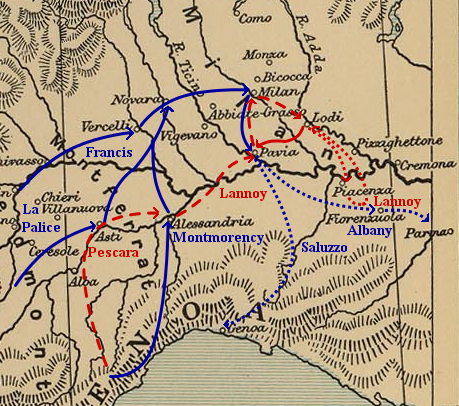

The French advance into Lombardy and the Pavia campaign of 1524–25. French movements are indicated in blue and Imperial movements in red.

Italy brought France the Renaissance, and France brought Italy warfare, strengthening the Valois Dynasty. However, war in Italy was about more than Italy. The peninsula was just one theater of the conflict between the Valois and Habsburg Dynasties for the domination of western Europe. When the Habsburg king of Spain, Charles V, became Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, France faced encirclement from the Spanish Netherlands to Germany to Spain to Italy. The wars were really about dynastic considerations and for the prestige and glory of the warrior-kings involved.

The French monarch, Francis I, began war against Charles in Italy in 1521 but was defeated and captured at Pavia in 1525. Charles imprisoned Francis in Spain and ransomed the king, who returned to France in 1527. After another round of fighting, the two monarchs made peace in 1529, and Francis married the emperor’s sister, Eleanor. The two monarchs fought further inconclusive wars from 1536 to 1538 and from 1542 to 1544. In this period, Francis, a Catholic, did not hesitate to ally against the Catholic Habsburgs with German Protestant princes and with Muslim Ottomans.

Yet these wars fought largely in Italy also sparked a revolution in military affairs that included the construction of great fortresses on the model called the trace italienne and saw the rise of the musket as the newest infantry weapon. By 1529, large standing armies were the norm, not small dynastic armies raised for a war and then disbanded. To pay for the armies and artillery now required in the new age of warfare, Francis I used his personal fortune to buy the loyalty of his nobles with titles and cash. He used the new form of patronage to control his nobles by creating vertical ties that bound them to him as tightly as had the old ties of feudalism.

The most significant battle of the period, Pavia (1525), was the first attack on France from Italy in centuries. Arquebusiers came out from behind their ramparts and attacked in ranks, in the first battle in which small arms fire was decisive. It was also a battle of surprise, maneuver, and massacre. The French lost 8,000 to the imperials’ 700. By 1530, successful sieges were a matter of execution, not invention. However, bastional fortresses on the Italian design were expensive, and only rich states or cities could afford them. Recognizing the importance of the fortress, the French began constructing a double line of fortresses in the northeast, which held through a lack of resolve among its enemies and would hold through the wars of Louis XIV.

The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559 that ended the Valois-Habsburg Wars also illustrated their international aspect beyond Italy. The French renounced any claims on the Italian peninsula, acquired Calais from the English, and secured Toul, Metz, and Verdun.

Ruprecht Heller, The Battle of Pavia (1529), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Battle of Pavia, (24 February 1525)

The turning point of the “Italian wars” and the end of the era of chivalry. By 1525, French kings had been claiming territories in Italy for 30 years. To reach their political goals, they had to face the thrones of Spain and Austria, which were combined in 1519, forming a threatening neighbor. The nature of the Italian wars changed as the new king, Charles V, ruled countries surrounding France on three sides. In 1524, the imperialist forces invaded Provence, but facing failure at the siege of Marseille, they had to retire in front of the main French army. Francis I, the king of France, decided to follow the retiring army in Italy.

The imperialists resisted the French invasion but had to fall back on their fortified garrisons of Pavia and Lodi. Francis decided (against the advice of his wiser commanders) to avoid a direct fight against the main imperialist army, led by the Marquis of Pescara. He chose instead to besiege Pavia.

The siege began on 28 October 1524. Facing superior French artillery, the Spanish commander Antonio de Levya made a stubborn defense. Unable to storm the town rapidly, Francis decided to make his winter quarters in a walled park, north of the siege work. The desertion rate among the mercenaries began to rise (8,000 Swiss on 20 February 1525 alone). Pescara’s army of 40,000, mainly Landsknecht (mercenary soldiers from the Holy Roman Empire), pikemen, harquebusiers, and light artillery, left Lodi and reached Pavia to find a waiting French army. The besieger was besieged in Mirabello Park.

The battle took place on 24 February 1525. During the night of the 23d-24th, the imperialists (23,000 soldiers) took the initiative. Their approach march turned around the high wall, and a breach was made in an unsuspected spot. Dawn took the French army of 22,000 unprepared and separated in three groups. Following the king, the French cavalry impetuously charged the Landsknecht as soon as they emerged from the wall while still masking their own artillery. Facing deadly fire, the French cavalry was cut to pieces, and the reinforcements, unable to stop the imperialists, were destroyed piecemeal. Francis I, wounded in the thick of the fray, was taken prisoner, and 10,000 French were killed, including hundreds of lords, as no mercy was given by either side.

This crushing defeat marked the beginning of a period of imperial control of Italy. “Tout est perdu, fors l’Honneur” (“All is lost but honor) was the comment made by Francis I, writing to his mother to announce his defeat.

References and further reading: Duffy, Christopher. Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World, 1494-1660. London: Routledge and Paul, 1979. Oman, Sir Charles. A History of the Art of War in Italy in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen, 1937. Taylor, F. L. The Art of War in Italy, 1459-1529. 1921. 2d ed., Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973. Cornette, Joel. Chronique de la France moderne, le XVIeme siecle. Paris: SEDES, 1995. Hardy, Etienne. Origines de la tactique française. Paris: Dumaine, 1881. Konstam, Angus. Pavia 1525. London: Osprey Publishers, 1996.