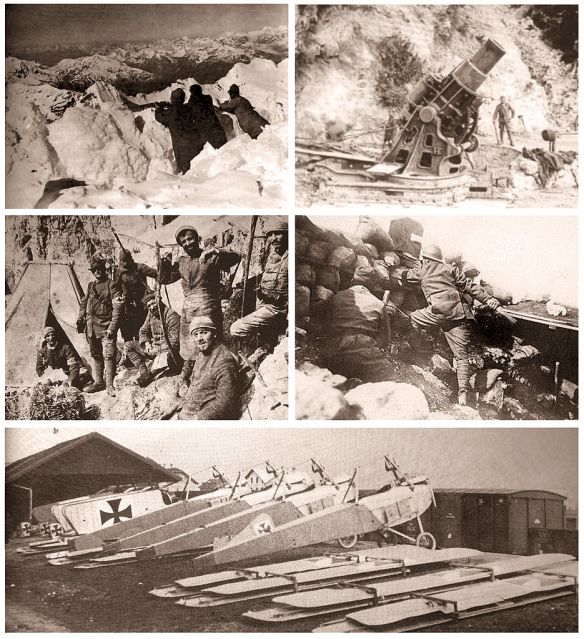

From left to right: Ortles, autumn 1917; Fort Verena, June 1915; Mount Paterno, 1915; Carso, 1917; Toblach, 1915.

The Italian Front in 1915–1917: eleven Battles of the Isonzo and Asiago offensive. In blue, initial Italian conquests

The Italians declared war against Austria-Hungary on 25 May. However, it would be several weeks before they would finish mobilising and start attacking and it would take even longer for their industrial base to begin supplying the ammunition their armies desperately needed to compete with Austria-Hungary’s veteran armies. Italy’s declaration of war surprised her own general staff and created a grim new opportunity for modern artillery to demonstrate its effectiveness. Operationally constrained by the Tyrol, the Italians sought to secure the Austrian Littoral along the Isonzo, including the Adriatic port of Trieste and the Istrian Peninsula – the area that nationalists saw as the Italia Irredenta (the natural border of Italy). Unfortunately these aspirations required the inexperienced Italian army to fight across some of the most difficult terrain in Europe against a skilled and determined opponent, and as a result the battlefield casualties were unprecedented.

Italy was poorly prepared for war, with a fraction of the resources of the Central Powers and an underdeveloped industrial base. Relations between different ranks, arms and services were poor and, although the artillery regulations were relatively sophisticated, senior officers appeared to make little attempt to study the lessons learned by either side in the expanding Great War. High illiteracy rates undermined the NCO cadre that Italy needed to ensure training and morale, and limited both innovation and expansion in the artillery. Most damagingly, low stocks of ammunition and slow mobilisation meant that Austro-Hungary had valuable time in which to secure her frontiers. The problems were exacerbated by the petulant character of General Luigi Cadorna, the recently appointed Italian Chief of the General Staff, an officer who had spent much of his time preparing for war with France. His belief in the efficacy of the frontal assault and immunity to advice from any quarter made him the stereotype of a First World War general.

Austria’s disasters in the Balkans and on the Russian Front were assumed to have created an opportunity for Italy to thrust across the Isonzo River through Gorizia towards Trieste, striking a blow at the heartland of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Austro-Hungarians were known to be pitifully weak along the Isonzo valley and Russian pressure was expected to pin down Austrian forces in the east. But the dramatic victory at Gorlice-Tarnow transformed the strategic situation and a number of veteran units were rapidly transferred to the Littoral in time to face Cadorna’s first offensive across the Isonzo.

The k. u. k. Armee was still weak in both the quality and quantity of its artillery and tactical methods, having yet to entirely absorb the lessons of the fighting in 1914. Most importantly, while Austro-Hungarian munitions production was expanding, it was struggling to keep up with the ever-increasing demands for ammunition, so stocks were low. Italy and Austro-Hungary had similar divisional structures but the Italians were initially far weaker in both heavy and mountain artillery; even after months of preparation, only 112 of Italy’s 2, 000 guns were heavy weapons, and doctrine assumed guns and not howitzers would handle counter-battery fire. Shell production was also a problem, with only 14, 000 rounds being produced a day, and the Italians would soon find themselves relying on their infantry to break through.

In the First Battle of the Isonzo most of the initial assaults ran into deter-mined resistance but specialist Alpini were able to secure the locally dominant Mount Krn and Cadorna’s men rolled forwards until the Austro-Hungarians managed to consolidate their defences and adapt their experiences on the Eastern Front to alpine conditions. Relieved by the Italian failure to break through, the Austrians were particularly stunned by Cadorna’s inability to seize the initiative in the still weakly held Tyrol. Krafft von Dellmensingen noted the `great caution’ shown by the Italians: `they approach the positions slowly, behind which they can place their artillery, and then immediately after they entrench underground. From a tactical point of view it is not an inept procedure but strategically they behave in an unconsidered manner. The opportune moment [.] passed…’.

General Svetozar Boroevic’, commanding the Austro-Hungarian Fifth Army, understood the importance of holding the key positions along the Isonzo and ensured that his men used every topographical advantage to hold their positions and issued standing orders for units to counter-attack at the earliest opportunity. Counter-attacks meant higher casualties but could roll back an attack if the Italians did not coordinate their infantry and artillery. The Italians soon discovered that carefully sited machine guns and concealed artillery, firing indirectly from kaverne blasted into the mountainside by construction units, were able to concentrate fire on the front ranks struggling up the mountainside; the terrain often canalised the attacking infantry into spearheads, creating near-perfect targets. A strategic prominence like Hill 383, near Plava, could be held by relatively few troops and only the Austrian ammunition supply limited the number of Italians that could be slaughtered by the hail of fire. If ammunition ran out, then a few desperate units found that throwing rocks could also be effective against decimated attackers. The Italians understood that they had a problem but their staff system was inherently dysfunctional and thus they had trouble finding solutions.

Italian artillery did not coordinate closely with their infantry and most of the shelling in the first battle was scattered across suspected Austro-Hungarian positions. Likely observation points received the most attention and the FOO position on Mount Santo (Sveta Gora), a famous medieval monastery overlooking Gorizia, was devastated in a full day’s bombardment. On the South Tyrol front the Tre Sassi Fort, covering the Val Badia, was blasted with over 200 shells in early July, rapidly collapsing the roof, but an enterprising Austrian officer ordered lights to be lit in the fort at night and the bombardment continued for an entire month!

Cadorna made no attempt to monitor and improve communications between the artillery and the infantry, and it is difficult to escape the impression that he believed that heavier and heavier bombardments followed by ever more vigorous frontal assaults could triumph against determined troops. Where the corpses could not be buried, they were scattered with quicklime, and both sides doggedly focused on preparing for the next phase of the campaign. The Austro-Hungarians extended their network of infantry and artillery kavernen while the Italians brought up more ammunition and replacements. Both sides recognised that the struggle had become one of grim attrition.

Cadorna increased the number of guns and stocks of ammunition for each of the battles on the Isonzo and the Fifth Army started to lose more men as the heavier artillery pieces pummelled their positions. On Mount St Michele, in the Carso region, the shelling reached unprecedented levels. One soldier noted `the gigantic, hard-pounding hammering of thousands of shells, which no words on God’s earth can express’, while another grimly prepared himself `to die bravely as a Christian’, writing, just before he was killed, `It’s all over. An unprecedented slaughter. A horrifying bloodbath. Blood flows everywhere, and the dead and pieces of corpses lie in circles, so that…’. But increasing the number of guns did not ensure the success of the assault; Italian infantry still advanced in dense columns and the rapid losses of both officers and standard bearers soon stalled the attacks.

Where breakthroughs did occur, the Austro-Hungarians sometimes succeeded in clearing the Italians from their hard-won prizes with determined attacks led by local reserves. The defenders soon learned that it was better to attack quickly with small numbers of men armed with knives and battle-clubs so that they were ready for the close-quarter battles that followed. Where successes occurred, it showed what Italian artillery could do, particularly when they had the ammunition to shell rear areas: 50 if Austrian reserves moved over obvious routes they would be shelled and the counter-attacks would usually fail. While the Italian artillery groupes were finding it difficult to support attacks and to assist the infantry against the menace of snipers (the hated cecchini), they were proving increasingly adept at hitting the areas behind the Fifth Army’s front line and were beginning to be used to support smaller-scale harassment raids. Observation positions in the mountains enabled any units in the open to be targeted and in one case a Croatian battalion was shattered while trying to return to the line after a rest. Italian artillery was also effective in defence. One Hungarian Honvéd division was blown apart in an over-enthusiastic counter-attack into the Italian start-line because the Italians had pre-planned defensive barrages.

Trench mortars were found to be useful for supporting limited attacks in the mountainous terrain and under continuous pressure both defensive systems gradually improved. While the Austro-Hungarians drilled and blasted more kavernen into the mountainsides and improved the water supply, with pumping stations to keep the defenders supplied, the Italians began to expand their own supply system, building what would become the Via Ferrata – a remarkable network of cables, ladders and bridges designed to improve the movement of supplies and ammunition into the front line.

By the Third Battle of the Isonzo, in October, Cadorna had tripled the number of heavy batteries and amassed a reserve of a million shells. He thought using old fortress guns and some French super-heavy howitzers could shatter the kavernen and break the Austrian artillery, but the preparations were obvious to Austrian observers and intelligence analysts, enabling the defenders to make final preparations and reallocate their meagre stocks of artillery ammunition. The bombardment lasted 70 hours but, for reasons that are still unexplained, there was a 2-hour gap before the Italians began the assault – more than enough time for the Austrian commanders to plug every gap created by the bombardment. Rudimentary body armour and helmets were no protection and the surviving Austrian artillery batteries tore into the assault columns. The Italian fanti died in droves.

The year ended with the Italians having made only marginal gains for huge losses. While they had increased their artillery reserves enormously, this material advantage had been countered by Austro-Hungarian defensive innovations and a vigorous, if costly, doctrine of immediate counter-attack.