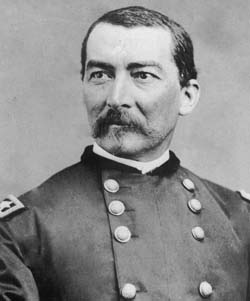

(1831-88) Civil War General

Philip Sheridan became one of Ulysses S. Grant’s top lieutenants by the end of the Civil War and personified perhaps more than any other general the remorseless determination necessary to achieve victory.

Sheridan graduated from the U. S. Military Academy at West Point in 1853 and served on the frontier until the outbreak of the Civil War. His early Civil War assignments were important but unglamorous postings in the quartermaster and commissary departments. In May 1862, however, Sheridan received the combat assignment he had long coveted, as colonel of a cavalry regiment. Autumn brought promotion to brigadier general and transfer to Kentucky, to command an infantry. Sheridan’s division was present at the battle of Perryville, but strict orders from his corps commander, who did not understand the situation on the battlefield, prevented it from engaging in major combat.

The division fought intensely at the battle of Stone’s River, winning badly needed time for Union forces to regroup. His promotion to major general was dated from the first day of Stone’s River, as recognition of his service there. At the battle of Chickamauga, Sheridan’s division fought fiercely but briefly in a vain attempt to stem the massive Confederate breakthrough. Sheridan rallied his division and was leading it back to the battlefield when he received orders to retreat.

On November 24, 1863, Sheridan’s division was one of four that broke through the Confederate defenses. Grant, who was in command on the battlefield, was impressed. Several months later when Grant moved to Virginia as commanding general of all Union armies, he took Sheridan with him to command the Army of the Potomac’s hitherto indifferently led cavalry corps.

When the spring offensive began in May 1864, Sheridan stumbled in his duties as cavalry commander, impeding the army’s progress and contributing to the failure to achieve decisive results in the battle of the Wilderness. For this reason and because of the personalities of both men, Sheridan clashed bitterly with Army of the Potomac commander (Grant’s subordinate), Maj. Gen. George G. Meade.

Grant directed Meade to dispatch Sheridan with two divisions of cavalry on a raid to the outskirts of Richmond. Sheridan’s troops defeated Jeb Stuart’s Confederate horsemen at Yellow Tavern not far from Richmond, mortally wounding Stuart himself. After the fight, Sheridan led his cavalry to join the Union Army of the James, east of Richmond, for a period of rest and refitting before returning to the Army of the Potomac. In early June, Grant dispatched Sheridan and his men on a raid to the west of Richmond, where the Union horsemen clashed with their Confederate counterparts at the indecisive two-day battle of Trevilian Station. Although Sheridan failed to cut the Confederate supply lines to Richmond, he did help to distract the attention of the Rebel cavalry away from Grant’s simultaneous move to the south bank of the James River.

In July, Gen. Robert E. Lee made use of the Shenandoah Valley to send a Confederate raiding force under Jubal Early all the way to the outskirts of Washington. Though Early soon had to retreat from the vicinity of the capital, he remained in the lower Shenandoah Valley, a thorn in the side of Union efforts in Virginia. On August 6, Grant assigned Sheridan to command the newly formed Army of the Shenandoah. On September 19, 1864, Sheridan’s 40,000 men defeated Early’s 12,000 at Winchester, Virginia. Sheridan caught up with the fleeing Early two days later at Fisher’s Hill and thrashed him again. Confident that Early’s army posed no further threat, Sheridan turned his attention to carrying out Grant’s order to render the Shenandoah Valley no longer useful to the Confederacy. On October 6, his army marched back down the valley. For more than seventy miles, Sheridan’s men killed or confiscated livestock, and burned barns, mills, and granaries.

Early, reinforced to 18,000 men, launched a surprise attack at Cedar Creek on October 19, driving the Union troops back in disorder. Sheridan, who had been attending a high command conference in Washington, was on his way back when he heard the sounds of firing. He rode from Winchester to Middletown, calling on stragglers to rally and return to the fight. Arriving on the battlefield, Sheridan regrouped his army and at 4 P. M. launched an attack of his own. Early’s army collapsed under the onslaught.

Sheridan was back with Grant in the spring of 1865 for the final offensive against Lee. On April 1, he commanded a task force that seized a key crossroads at Five Forks, west of Petersburg, but he was dissatisfied with the performance of his subordinate, V Corps Comm. Gouverneur K. Warren. Using authority Grant had given him, Sheridan summarily sacked Warren. Though probably not warranted by Warren’s performance on that day, the action was more than justified by that general’s dismal record of non-cooperation over the preceding months. Thereafter Sheridan played a key role in cornering the Confederates at Appomattox Court House.

After the war Sheridan commanded U. S. troops sent to the Mexican border to threaten Emperor Maximilian and persuade Napoleon III to withdraw his troops from Mexico. Sheridan also briefly administered Reconstruction in Texas and Louisiana, where he favored a stern treatment of former Rebels. His strict rule was nevertheless insufficient to prevent a July 30, 1866, riot perpetrated by the New Orleans police against blacks in the city, which killed 34 of them. Sheridan’s willingness to be firm with recalcitrant white southerners earned him the displeasure of Pres. Andrew Johnson, who favored a more conciliatory approach.

Thereafter Sheridan commanded troops contending with American Indians on the Great Plains. Recognizing the superior mobility of the Plains Indians, Sheridan finally prevailed over them by a policy of relentless pressure, such as the 1868 winter campaign that produced George A. Custer’s victory at the Washita River, in what is today Oklahoma. As in his operations against the Rebels, Sheridan was hard and remorseless. One witness attributed to him the statement, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” though Sheridan denied having used that expression. He directed most of the operations on the Great Plains from his headquarters in Chicago, where in October 1871 he acted energetically to help stop the infamous Chicago fire and provide relief for the citizens of the damaged city. From 1884 until his death in 1888, he was commanding general of the U. S. Army.

Although neither as skillful nor as aggressive as Grant, Sheridan was one of Grant’s most important subordinates during the final year of the war. He provided the relentless, hard-hitting leadership necessary to bring the conflict to a successful close.

Bibliography Hergesheimer, Joseph. Sheridan: A Military Narrative. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1931. Hutton, Paul Andrew. Phil Sheridan and His Army. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985. Sheridan, Philip Henry. Civil War Memoirs. New York: Bantam, 1991. Further Reading Lewis, Thomas A. The Guns of Cedar Creek. New York: Harper & Row, 1988. Morris, Roy, Jr. Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan. New York: Random House, 1992. Stackpole, Edward J. Sheridan in the Shenandoah: Jubal Early’s Nemesis. Harrisburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 1992.