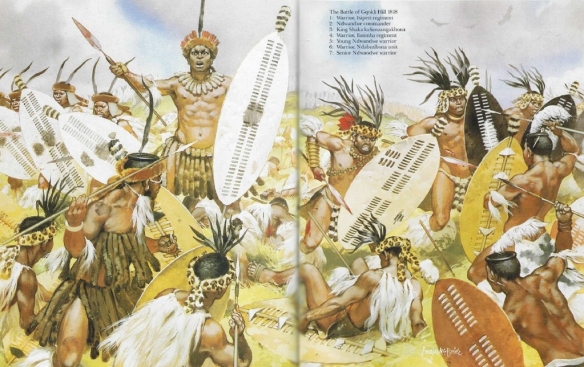

Gqokli 1818 Rise of Shaka Zulu. On a bloody offensive after assuming the Zulu throne, the young warrior Shaka moved against his rival Zwide of the Ndwandwe, who had killed the King’s mentor, Dingiswayo. In Shaka’s first great victory, at Gqokli near Ulundi, Zwide’s larger force under Nomahlanjana was routed-with a claimed 7,000 killed out of 12,000. He was finally beaten the following year at Mhlatuze (April 1819).

PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Zulus vs. Ndwandwe (and other tribes)

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Zululand (Natal and South Africa)

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Shaka, chief of the Zulus, forged an army of conquest, with which he ravaged and dominated his neighbors to create a great African empire.

OUTCOME: Shaka and the Zulus emerged as the most powerful force in southern Africa.

Shaka (c. 1787-1828), the great warrior leader of the Mtetwa people of South Africa, had rebelled against his father, Senzangakona (d. 1816), a Zulu chief. Upon the death of his father, Shaka returned to the Zulus and, with the aid of the principal chief of the Mtetwa, Dingiswayo (d. 1817), earned recognition as the new chief of the Zulus in 1816.

The bond between Shaka and Dingiswayo was powerful. The two allied their peoples against common enemies, including the Ndwandwe tribe led by Chief Zwide (d. 1819). In 1817, Zwide murdered Dingiswayo, and, in the absence of their chief, the Mtetwa rallied to Shaka and proclaimed themselves no longer Mtetwas but Zulus.

With his realm thus augmented, Shaka revealed himself a military genius. He enlarged the Zulu army and transformed it from a poorly armed and inadequately trained mob into a disciplined force, equipped with the assegai, a revolutionary light javelin far superior to the traditional long throwing spear. The assegai could be hurled or used in close combat. Shaka also discarded the small shield that warriors formerly used and adopted instead a shield that covered the entire front of the body. As for strategy and tactics, Shaka reexamined and revised these extensively. Traditionally, native warriors battled each other from a distance, threw their spears, jeered at each other, then ended the fight. It was rare that a clear-cut winner emerged from these halfhearted contests.

Shaka made his warriors fierce, encouraging them to move in close, protect themselves with the large shield, and slash with the short assegai. Using many of the same tactics that had once made the Roman legions the best fighting force in the world, Shaka’s Zulu regiments, called impis, would overwhelm their opponents with a pressing frontal assault while the “horns” of the Zulu crescent battle formation swept around enemy flanks in a double envelopment. Although he had no cavalry, Shaka’s loping impis covered ground as fast as mounted troops and ripped into enemy lines under a hail of hurled spears, stabbing their assegais at the rawhide shields of their opponents with a deadly and frighteningly controlled rhythm. In this way, ritual combat became outright war, and the Zulus became the foremost warriors of black Africa in the 19th century.

In 1818, at the Battle of Gqokoli Hill, Shaka led his troops to victory against the far superior numbers fielded by the Ndwandwes. In the rout that followed, Zwide was killed, and most of the Ndwandwes fled their lands, leaving vast tracts to be gathered up by Shaka. Following the victory over the Ndwandwes, Shaka initiated the Mfecane- “The Crushing”-a sequence of wars that ravaged the region surrounding Zululand through the early 1820s. At the end of the Crushing, Shaka was effectively monarch of a large Zulu empire, which extended over the region now occupied by Natal and other parts of South Africa.

Further reading: Ian Knight, Warrior Chiefs of Southern Africa (Poole, Dorset: Firebird Books; New York: Sterling, 1994).