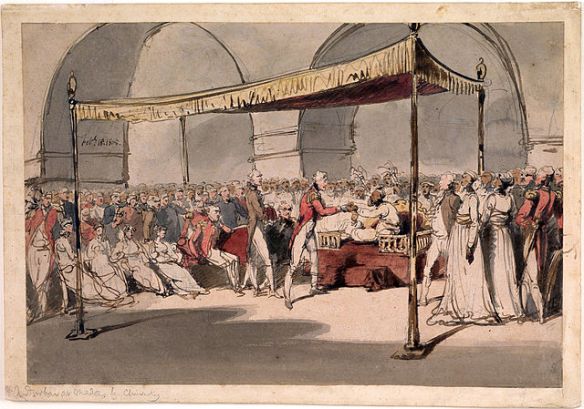

Major-General Wellesley, meeting with Nawab Azim al-Daula, 1805.

Major General Wellesley (mounted) commanding his troops at the Battle of Assaye (J.C. Stadler after W.Heath)

India proved a valuable training ground for Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington. Wellesley’s success, like that of Bugeaud in Algeria, relied principally on his organization and tactical methods, rather than on technological superiority. He maximized the use of strategic surprise by increasing the mobility and striking power of his forces. Wellesley in India, wearing his major-general’s uniform, 1804.

The foundation of Wellesley’s success in India was organizational. Earlier commanders in India like Clive had fought close to base because they lacked the logistical capacity to strike deep into the enemy heartland. In India, as elsewhere in colonial warfare, it was an axiom that a large force starved while a small one risked defeat. On his arrival in India, Wellesley discovered that British expeditions resembled migrating people rather than an army. As many as 20,000 troops organized in a single force lumbered over the countryside, averaging 10 miles on a good day, but requiring one day’s rest in three, and forced to meander to find food and fodder. Wellesley recognized that strategic success could result only after his army was reorganized along lines that would allow greater mobility. In his campaign against Dhoondiah in Mysore, Wellesley divided his forces into four armies, which kept his opponent guessing and allowed the British to march up to 26 miles a day to achieve surprise.

#

Peace between the British and the Marathas would last for the next two decades, until a succession crisis shook the confederacy in 1803. Defeated by his rival, Holkar of Indore, Baji Rao II entered into the Bassein Treaty (1803), by which the British agreed to restore Baji as Peshwa in return for the Marathas accepting and paying for British troops in their capital, together with other obligations. To restore Baji Rao and bring those princes who rejected the Bassein Treaty to heel, Governor General Sir Richard Wellesley planned a twofold campaign against the Marathas. First, Wellesley’s brother, Arthur, would lead a force of 9,000 Europeans and 5,000 Indian troops into the Maratha homeland. A second force under Gerard Lake invaded Hindustan. In March 1803, Wellesley’s force captured Pune and restored Baji as Peshwa. On 23 September 1803, Wellesley’s army met and defeated the Marathas under Doulut Rao Sindhia at Assaye. Though victorious, Wellesley would later recall this campaign as the hardest-fought action of his long career. Meanwhile, Lake captured Delhi on 16 September 1803 and in the Battle of Laswari (1 November) finally destroyed the forces of the Maratha prince, Sindhia. In the meantime, the British government had grown concerned with the extent of these operations. In particular, the siege of Bhurtpore (January- April 1805) had claimed 3,100 men before the British were victorious. Accordingly, Lord Wellesley was recalled, and with the capitulation of Holkar at Amritsar (December 1805), the Second Maratha War came to an uneasy close.

Sir Arthur Wellesley

In India from 1796 to 1805, where his elder brother Richard was governor general from 1797 to 1805, he achieved decisive victories at Seringapatam in 1799 and Poona, Ahmadnagar, Assaye, Argaon, and Gawilgarh in 1803.

Assaye

The first and most hard-fought victory of Arthur Wellesley (later duke of Wellington). Eighteenth-century India witnessed the rise and decay of the Maratha Empire. The Maratha War of 1775-1782 had resulted in a humiliating defeat of the East India Company’s forces. The two major opponents of the British during the second Anglo Maratha War were Scindia, maharajah of Gwalior, and Bhoonsla, rajah of Berar. Arthur Wellesley’s force was part of an army assembled on the northwestern Mysore border. By early August, negotiations with Scindia and Governor General Wellesley having failed, the latter moved against the two principal Maratha forces. After storming the city of Ahmednuggur, Wellesley’s tiny army of 6,000 men advanced against Scindia’s army of 50,000 men. (Scindia’s infantry has been trained by European officers and was commanded by a German officer.) Early on 23 September, Wellesley received intelligence that the enemy were camped behind the Kaitna River, close to its junction with the River Jooee. He decided to outflank the Indian camp and crossed the Kaitna to deploy in the V formed by the two rivers. Maratha and Mysore allied cavalry (of dubious loyalty) were left to face Scindia’s cavalry on the southern bank of the Kaitna River. Maratha’s reactions were swift and Wellesley’s attack sustained heavy casualties in their frontal advance against Indian artillery. But because the front narrowed as the two rivers flowed toward their confluence, Maratha’s troops were able to deploy only a fraction of their strength. The British initiative was checked for three hours before a devastating volley from the 74th and 78th Foot routed the regular Indian infantry.

By 6 P. M., the battle was over, but Wellesley’s crippled army could not pursue the fleeing Marathas. Wellesley was later to contend that Assaye was his greatest victory and proportionally the bloodiest action he had ever witnessed. His casualties amounted to one-third of his force. The defeat of the Maratha army caused Scindia to sue for peace, but hostilities continued until 1805.

Assaye revealed Wellesley’s potential as a field tactician and he was soon recalled in Europe to deal with less exotic opponents who more directly threatened Great Britain.

References and further reading: Asquith, Stuart, and Charles Grant. Wellington in India. Upavon: CSG, 1995. Weller, Jim. Wellington in India. London: Greenhill Books, 1993.