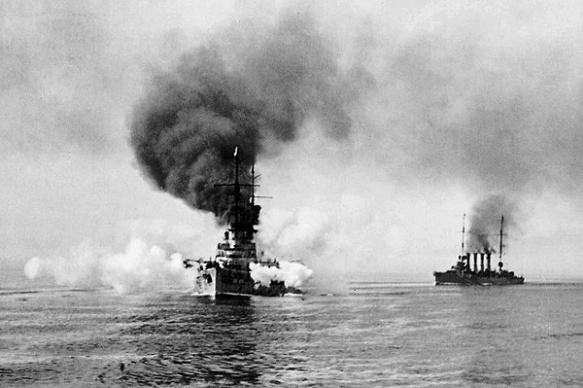

Goeben and Breslau

The possibility of an early and classic naval battle between capital ships of the Triple Alliance (Austria-Hungary, Italy, Germany) and the British and French ended when the Italians proclaimed their neutrality at the beginning of the war. The Austrian commander Admiral Anton Haus, who had been designated to lead the Triple Alliance fleets, was left in a position of hopeless inferiority, doomed to a defensive stance in the Adriatic.

Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, commander of the German Mediterranean Division, consisting of the battle cruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau, was not content to be shut up with the Austrians in the Adriatic and elected to make for the Dardanelles. Souchon succeeded, largely because French commander in chief Vice Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère was preoccupied with protecting the transport of French troops from North Africa to metropolitan France and British Mediterranean commanders Admiral Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne and Rear Admiral E. C. T. Troubridge suffered from ambiguous orders from the Admiralty about avoiding being brought to action with “superior force.” The Admiralty meant the Austrian fleet, but when Troubridge was in a position to intercept the Goeben with his squadron of four armored cruisers, each manifestly inferior to the German battle cruiser, he interpreted his orders to mean the Goeben and turned away. Souchon ultimately reached the safety of the Dardanelles, and Troubridge was court-martialed, although acquitted.

The German ships were then “sold” to Turkey and hoisted the Ottoman flag, although the Germans retained control. Their presence in Turkish waters meant that an Allied force had to be maintained off the Dardanelles watching them, and Souchon colluded with the pro-German faction in the Turkish government to bring Turkey into the war on the side of the Central Powers by launching a bombardment of Russian ports in the Black Sea.

The British, expecting the major action to be in the North Sea, were only too happy to turn over command in the Mediterranean to the French. On 6 August they signed a convention giving the French the general direction of the war in the Mediterranean. However, there were soon exceptions, such as the eastern Aegean off the Dardanelles, and as the war dragged on, the British found they had too many interests in the Mediterranean to leave it to the French, and so, step-by-step, they resumed their traditional role. By the last year of the war, they were, in effect, directing the crucial struggle against submarines, although the nominal French command remained.

To a large extent the French battle fleet had really been built to fight the Italians, and the French now found it hard to bring their superior strength against the Austrians in the Adriatic. They were hampered by the lack of a suitable base but eventually were allowed to make use of theoretically neutral Greek islands in the Ionian with the collusion of the pro-Allied Greek Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos. Nevertheless, even the handful of submarines that were available to the Austrians at the beginning of the war sufficed to make incursions into the Adriatic too dangerous for the big ships, although at first there were periodic sweeps, particularly to escort ships carrying supplies to Montenegro.

There was no major encounter. Haus was far too sensible to risk his big battleships in an unequal clash he was likely to lose and resisted impracticable suggestions that he take his fleet to Constantinople. His mistrust of his former Italian allies was justified when Italy entered the war against Austria in May 1915. Haus brought the Austrian fleet across the Adriatic for a surprise bombardment of Italian ports, largely for the psychological advantage involved, but never took the entire fleet out again. The war in the Adriatic became essentially a conflict between light forces, with raids and increasing use of aircraft. The Italians learned the same hard lessons about submarines that the French had, and after a few painful losses large ships were rarely risked deep in the Adriatic.

In the Mediterranean as a whole the Allies had at first unchallenged use of the sea, a situation that facilitated the beginning of the Dardanelles campaign. Unfortunately, the Dardanelles campaign had an unwelcome consequence, for after the Austrians refused German requests to send surface ships to the Dardanelles and did not have submarines capable of operating far outside of the Adriatic, the Germans elected to send their own submarines. These were at first small boats transported by rail in sections and reassembled at Pola, but larger submarines, capable of making the long voyage from Germany on their own, soon followed. The Germans used the Austrian bases at Pola and in the Gulf of Cattaro and quickly scored successes at the Dardanelles, forcing the British to make extensive use of netting and small craft. The Germans did not halt the Dardanelles campaign but they certainly complicated it.

The Germans gradually discovered that their most effective work would be against Allied supply lines in the Mediterranean. Coordination between the Allies at first was poor, and ultimately only the British had the large numbers of small craft necessary for antisubmarine operations. This was a major factor in the de facto resumption of British direction of the naval war in the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean was also attractive to the Germans for diplomatic reasons. In 1915–1916 there were few chances of sinking American ships with the diplomatic consequences that would follow.

In the autumn of 1915 the entry of Bulgaria into the war led to a concerted Austrian-German-Bulgarian offensive that overran Serbia. The Allied effort to assist, too little and too late, led to the establishment of the Salonika front. The supply of this new front eventually became an onerous responsibility because the route through the Mediterranean was exposed to the depredations of submarines. The remnants of the Serbian army made an epic retreat over the Albanian mountains to the coast, where, in an evacuation similar to that of Dunkirk during World War II, they were taken to Corfu, reorganized, and eventually brought to the Salonika front to resume the struggle.

The Austrian navy made no serious attempt to disrupt the evacuation although, on 29 December 1915, its ships raided the Albanian port of Durazzo. It lost two precious modern destroyers to mines and was lucky to escape from the superior Allied forces based at Brindisi that attempted to cut it off. This was one of the few surface actions of any size in the Adriatic. A stronger effort by the Austrians in the ensuing weeks might have disrupted the evacuation, but no such attempt was made. Haus preferred to preserve his big ships as a “fleet in being,” raising the potential cost of any Allied operation against the Austrian coast. Action in the Adriatic remained limited to light forces.

The Allies attempted to close the Straits of Otranto. This took the form of a barrage established by British drifters, gradually expanded and eventually including a fixed mine-net obstruction. It was mostly ineffective, although in May 1917 the Austrians raided the barrage, sinking a number of drifters. Once again a running battle ensued in which the Austrians were lucky to escape in what was the most prolonged surface encounter in the Adriatic during the war. In June 1918 the new and aggressive Austrian commander Rear Admiral Miklós Horthy de Nagybána planned a raid employing the Austrian dreadnoughts in support. It was aborted after part of his force ran into Italian MAS (motor torpedo) boats on their way south during the night, and the dreadnought Szent István was sunk.

The German submarine menace was contained with the eventual establishment of an elaborate convoy system in the Mediterranean and a central direction for antisubmarine warfare at Malta. Nevertheless Mediterranean losses remained relatively high, possibly because there were choke points that facilitated the submarines’ task. In 1918 the threat of surface action reappeared when the Goeben and Breslau sortied out of the Dardanelles to sink two British monitors at Imbros, although Breslau was lost to a mine. The Allies were fearful that after Russia was eliminated from the war, the Germans would be able to seize the Russian Black Sea fleet and use its ships for another sortie into the Aegean.

Because neither the Italians nor the French could agree on command in the Adriatic, both had battle fleets at the entrance to the Adriatic watching the Austrians and relatively weak forces in the Aegean. The British tried unsuccessfully to have a Mediterranean admiralissimo named, with Jellicoe the likely candidate. In the long run the threat of the former Russian Black Sea fleet proved to be a mirage; the Germans and Turks were able to put only a handful of ships into service by the end of the war.

The final year of the war also saw the Americans enter the Mediterranean. A motley collection of mostly old American gunboats and destroyers worked out of Gibraltar, and the Americans pushed plans for an amphibious landing on the Sabbioncello Peninsula on the Dalmatian coast. The troops were eventually diverted to France as a result of the Ludendorff Offensive, although a squadron of American “submarine chasers” joined the forces blockading the Straits of Otranto. These 110-foot wooden craft were to work in groups of three and use hydrophones to detect submarines. Despite high hopes, this technique proved ineffective. The naval war in the Mediterranean remained until the very end primarily one against submarines.

Anton, Baron von Haus, (1851–1917)

Grossadmiral and Marinekommandant of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1913–1917. Although little known to Britons and Americans, in 1914 Anton Haus was the designated commander of the Triple Alliance fleets in the Mediterranean. Born in Tolmein in the Küstenland on 13 June 1851, Anton Haus entered the navy in 1869. After a distinguished career he seemed almost the inevitable choice to be commander in chief (Marinekommandant) of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in 1913. By this time the navy was in an unprecedented period of expansion, changing from a purely coastal defense force into one with dreadnoughts capable of blue-water operations. This transformation created a new situation in the Mediterranean, for if the Austrians and Italians (both allies and rivals) combined their forces they had sufficient strength to seriously contest the French for naval supremacy, especially since British naval forces were increasingly concentrated in home waters. The result of this was the Triple Alliance Naval Convention of 1913, anticipating in the event of war a combination of Austrian, Italian, and German naval forces in Sicilian waters.

After Italy’s decision to remain neutral on the outbreak of war, Haus was left far inferior to the French and British forces in the Mediterranean. He resisted German proposals to send the fleet to Constantinople and made skillful use of the geographical configuration of the Adriatic and his few submarines to prevent the French from bringing their superior strength to bear. With the onset of the Dardanelles campaign, he again had to resist pressure from the Germans and some in the Austrian military to send the fleet to Constantinople. When Italy entered the war, he brought the entire fleet across the Adriatic to deliver a surprise bombardment on selected points on the Italian coast, hoping to obtain a psychological edge. On the whole, though, he remained on the defensive with his big ships as the classic “fleet-in-being,” raising the stakes by their very existence for any projects the Entente may have had in the Adriatic. Observing the spectacular success of the German submarines operating from Austrian bases, Haus eventually became probably the strongest supporter in Austria of unrestricted submarine warfare. On his return from the conference with the Germans at Schloss Pless in January 1917, on the eve of Germany’s fateful decision to launch unrestricted submarine warfare, he caught pneumonia and died aboard his flagship in Pola on 8 February 1917.

Maximilian Njegovan, (1858–1930)

Admiral and commander of the Austro-Hungarian Navy (February 1917–February 1918). Born in Agram on 31 October 1858 Maximilian Njegovan became one of the highest-ranking Croatians in the Austro-Hungarian Navy. He graduated from the Marine Academy at Fiume in 1877 and by the outbreak of the war in 1914 commanded the 1st division of the fleet, which contained the handful of modern capital ships that were the core of Austrian naval strength.

Njegovan succeeded Admiral Anton von Haus as commander of the fleet (Marinekommandant) on the latter’s death in 1917 and followed his defensive strategy of keeping the big ships as a “fleet-in-being” to raise the potential risks for any Allied plans in the Adriatic. However, the brilliant Haus was a hard act to follow, and by this time the tide was turning against Austria. There was growing war weariness, and Austria-Hungary’s opponents were growing stronger and bolder. The Italians, for example, had developed the fast MAS (motor torpedo) boats and succeeded in sinking the coast defense ship Wien in Trieste harbor in December 1917. Njegovan was criticized for failing to use the fleet aggressively enough in support of the Caporetto offensive, and there was a widespread call for “rejuvenation” of the high command. In February 1918 a mutiny occurred in the Gulf of Cattaro, and though it was quelled, Njegovan retired at his own request. He was replaced by the younger and reputedly more aggressive Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya. Njegovan died in Agram on 1 July 1930.

References

Corbett, Julian S., and Henry Newbolt. History of the Great War: Naval Operations. 5 vols. in 9. London: Longmans, Green, 1920–1931.

Ferrante, Ezio. La Grande Guerra in Adriatico: Nel lxx anniversario della vittoria. Rome: Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, 1987.

Halpern, Paul G. The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1914–1918. London: Allen & Unwin; Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Thomazi, A. La Guerre navale dans la Méditerranée. Paris: Payot, 1929.

Bayer von Bayersburg, Heinrich. Unter der k.u.k. Kriegsflagge, 1914–1918. Vienna: Bergland Verlag, 1959.

Halpern, Paul G. The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1914–1918. London: Allen & Unwin; Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Sokol, Hans Hugo. Österreich-Ungarns Seekrieg. 2 vols. Vienna: Amalthea Verlag, 1933. Reprint, Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, 1967.

Sondhaus, Lawrence. The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1994.