The carnage was frightful. Although the French army published no formal casualty lists, its official history, Les armées françaises dans la grande guerre, set losses for August at 206,515 men and for September at 213,445; those for the ten days at the Marne surely must have approached 40 percent of the latter figure. The chapel of the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr, before its destruction in World War II, had only a single entry for its dead of the first year of the war: “The Class of 1914.” In terms of natural resources and industrial production, France had lost 64 percent of its iron, 62 percent of its steel, and 50 percent of its coal.

The German army likewise published no official figures for the Marne. But according to its ten-day casualty reports, the armies in the west sustained 99,079 casualties between 1 and 10 September:

#

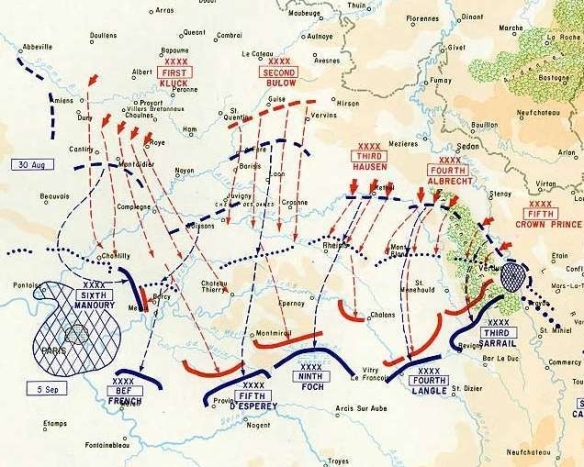

Unsurprisingly, the army corps that took the brunt of the fighting during that ten-day period suffered most heavily: Hans von Gronau’s IV Reserve Corps with First Army (2,676 killed or missing and 1,534 wounded); Otto von Emmich’s X Corps with Second Army (1,553 killed or missing and 2,688 wounded); and Maximilian von Laffert’s XIX Corps with Saxon Third Army (2,197 killed or missing and 2,982 wounded).23 Taking together all five German armies between Verdun and Paris, roughly 67,700 Landser were rendered hors de combat in the Battle of the Marne. Total British casualties at the Marne were 1,701.

Horses died in equally horrid numbers. For the first year of the war, no one bothered to keep records: The historians of the Reichsarchiv at Potsdam in the 1920s could not find the files of a single cavalry division with regard to “sickness or loss of horses.” Only 22d Infantry Division kept tabs from the start of the war in Belgium, and it reported a loss rate of roughly 30 percent. Most were the result not of combat but rather of exhaustion, colic, saddle sores, lung disease, withers’ fistulas, and improper shoeing. And since there yet existed no veterinary clinics, sick or wounded animals were simply shot in the field— and thus escaped official records. During the course of the Great War, Germany lost an estimated one million horses dead and seven million wounded.

Artillery ruled the battlefield. The German 105mm and 150mm howitzers, called “cooking pots” (marmites) by the French and “Jack Johnsons” by the British, and the lighter 77mm guns ripped men and horses alike into shreds of flesh and deposited their remains as mounds of pulp. The French 75s, dubbed “black butchers” by the Germans, filled the air with shrieking shrapnel shells (rafales) that exploded above the enemy and drenched those below with thousands of iron balls. For four weeks, “crude, stinking, crowded ambulance wagons” jostled the wounded back to barns and churches hastily converted into field hospitals, where the unfortunates lay for hours “in a cloud of flies drinking [their] blood.” For days, in words historian Robert Asprey addressed to the “common soldier” of 1914, “you ate nothing, drank nothing, no one washed you, your bandages went unchanged, many of you died.” The living moved on, a mass of stinking humanity advancing through “a reeking foul air of dead and dying cattle and mutilated horses” to fight another battle, another day.

The murderous nature of industrialized warfare changed the common soldiers who conducted it. Regardless of social, regional, or religious origin, they wrote home of the filth and dirt, horror and fear, of their frontline experiences. Some remembered the initial euphoria of marching through fall-clad orchards, the camaraderie among soldiers, the welcome mail calls, the “playing at cowboys and Indians” while advancing through woods, and the “liberating” of wonderful wine cellars. Most remembered the constant nagging hunger and thirst, the endless marches by day and night, the choking dust, the searing heat, then the cold rain and oozing mud, the burning villages, the groaning of the wounded, and the deathly rattle of the dying.

An anonymous German soldier, presumably a former miner, wrote to the Bergarbeiter-Zeitung in Bochum just after the Marne, “My opinion about the war itself has remained the same: it is murder and slaughter, and it is still incomprehensible to me today that humankind in the twentieth century could commit such slaughter.” A university professor, “von Drygalski,” at about the same time expressed his feelings of the war experience in similar but more prosaic terms. “I have seen so much that is grand, beautiful, monstrous, base, brutal, heinous, and gruesome, that like all the others I am totally stupefied. To see people die hardly interrupts the enjoyment of the coffee that one has triumphantly brewed in stark filth while under artillery fire.”

A French poilu, the future renowned violoncellist Maurice Maréchal, expressed much the same disillusion with the war in early September. His initial “beautiful, innocent joy” at news of “Victory! Victory!” at the Marne quickly “took flight” as he surveyed the battlefield:

There, a lieutenant of the 74th [Infantry Regiment], there, a captain of the 129th, all in groups of three or four, sometime singly and still in the position of firing prone, red pants. These are ours, these are our brothers, this is our blood. … Oh! Horrible people who wanted this war, there is no torment enough for you!

Three weeks later, Maréchal reflected again on the war. “Oh, this is long and monotonous and depressing.” The “energy” and the “heroism” of 1870–71 were absent on the Western Front in 1914. “The heroism of today: hide as best as possible.” Only the carnage was the same. “We feel small, so small, in the face of this frightening thing, some with bloody arms, others with boots ripped to shreds by red holes.” The meaning of it all escaped him. “We do not know, not really, if we have done anything of use for the country.”

The newly promoted Adjutant Bloch of French 272d Infantry Regiment by year’s end had overcome his “war euphoria” of August. “I led a life as different as possible from my ordinary existence: a life at once barbarous, violent, often colorful, also often a dreary monotony combined with bits of comedy and moments of grim tragedy.” Thereafter, he experienced primarily the “dreary monotony” of what he called the “age of mud”: constant downpours, caved-in trenches, and unrelieved dampness. “Our clothing was completely soaked for days on end. Our feet were chilled. The sticky clay clung to our shoes, our clothing, our underwear, our skin; it spoiled our food, threatened to plug the barrels of our rifles and to jam their breeches.” Typhoid fever, contracted in the damp netherworld of the trenches, came almost as a relief to him in January 1915.

Above all, the Battle of the Marne destroyed once and for all romantic notions of war. “Wish it were a fresh and jolly [frisch und fröhlich] tussle,” Robert Marcus, a German student, wrote his parents from the Argonne Forest, “rather than this malicious, gruesome mass assassination.” Mines, hand grenades, and flamethrowers had reduced warfare to a new form of barbarism. “Is such a manner of warfare still compatible with human dignity?” he rhetorically asked his parents.

Yet, despite the savage nature of warfare in the west, morale held. There were no widespread refusals to obey the call-ups in August 1914; large numbers of volunteers (even if grossly exaggerated for public consumption) rushed to the recruiting depots; and no major “rebellions” or “strikes” took place either at home or at the front. None of the armies kept statistics on “fragging” (shooting of officers) or on desertions. Wherever casualties were broken down under the headings of “cause,” possible deserters were lumped into the generic category of “missing,” which likely referred primarily to prisoners of war. Statistics for the seven German armies in the west show 21 suicides for August and a mere 6 for September 1914. The highest incidence was in Bavarian Sixth Army, with 8 suicides (among 228,680 soldiers); of these, 6 occurred before the army had even marched off to the front. Alcohol and fear of not being up to the task that lay ahead figured in most cases; almost all involved gunfire. And if one considers that Germany in 1914 suffered 800,000 casualties (including 18,000 officers), then the 251 suicides (including 19 officers) for that period are statistically insignificant and further proof of the inner steadfastness of those forces.

The Battle of the Marne did not, of course, dictate another four years of murderous warfare. If anything, it prefigured the resilience of European militaries and societies to endure horrendous sacrifices. To be sure, some historians have suggested that Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg’s infamous “war-aims program” of 9 September, at the very height of the struggle at the Marne, committed Germany to push on to victory regardless of the cost. But there were those at Imperial Headquarters who fully understood that the time had come in the fall of 1914 to end the Great Folly. Field Marshal Gottlieb von Haeseler, activated for field duty at the tender age of seventy-eight, advised Wilhelm II to sheath the sword. “It seems to me that the moment has come which we must try to end the war.” The kaiser refused the advice. Moltke’s successor, Erich von Falkenhayn, by 19 November had reached the same conclusion as Haeseler before him. Victory lay beyond reach. It would be “impossible,” he lectured Bethmann Hollweg, to “beat” the Allied armies “to such a point where we can come to a decent peace.” By continuing the war, Germany “would run the danger of slowly exhausting ourselves.” The chancellor rejected the counsel.

It began at the Marne in 1914. It ended at Versailles in 1919. In between, about sixty million young men had been mobilized, ten million killed, and twenty million wounded. With the 20/20 vision of hindsight, the great tragedy of the Marne is that it was strategically indecisive. Had German First Army destroyed French Sixth Army east of Paris; had French Fifth Army and the BEF driven through the gap between German First and Second armies expeditiously; had French Fifth Army pursued German Second Army more energetically beyond the Marne; then perhaps the world would have been spared the greater catastrophe that was to follow in 1939–45.