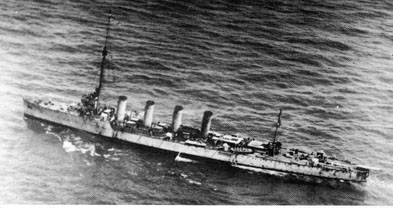

Aerial view of the damaged Austrian cruiser Novara following the Battle of the Otranto Straits, 15 May 1917.

Generally the term Austro-Hungarian navy refers to the navy of the Hapsburg Empire, even though the dual monarchy of Austria and Hungary did not exist until 1867. Previously equipped only with small gunboats, the Austrian Empire became a sea power in 1797 when the Treaty of Campo Formio ceded territory and numerous naval vessels of the Venetian Republic to Austria. By the end of the Napoléonic Wars, Vienna had acquired a fleet of a dozen ships of the line as well as frigates and corvettes.

Despite such a sudden increase in the size of the navy, several factors prevented the Hapsburg Empire from becoming a significant factor at sea in the early nineteenth century. Lack of support in the government and court for the navy led to constant funding difficulties. Also, drawn as they were from the Venetian navy, the majority of the officer corps and sailors were Italians, which proved a problem with the rise of Italian nationalism.

After the failed 1848 revolutions, German replaced Italian as the official language of the navy and the proportion of Italians in the fleet dropped significantly. Previously of secondary importance among Balkan seaports, Pola also replaced Venice as the primary naval base, this to minimize Italian influence in the fleet.

The navy achieved a degree of fame during its early history mostly due to support from members of the Hapsburg family. In 1830 the Italian Franciso Bandiera forced the sultan of Morocco to stop pirate attacks on Austrian merchant ships. Archduke Frederick employed the navy in the 1840s more actively than his predecessors, the most notable example being his participation in an international coalition against Egypt. Archduke Ferdinand Max, later Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, was another member of the Hapsburg dynasty who had a lasting influence. Between 1854 and 1864 he removed the fleet from army control, launched a frigate and corvette building program, and significantly improved training and naval facilities. He exploited the threat of Italian nationalism to win acceptance for his program in the government. Partly because of his efforts, the Austrian fleet was able to break a Danish naval blockade in the Battle of Helgoland (4 May 1864) during the Schleswig-Holstein War.

Competition with the Italian navy characterized the Austro-Hungarian fleet’s activity during the half century preceding World War I. Austrian Vice Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff’s victory against a larger Italian fleet in the Battle of Lissa (20 July 1866) was a payoff of efforts during the previous decade.

Later, as Marinekommandant, Tegetthoff introduced a number of reforms while constantly fighting for additional funds for the navy, which became even more complicated after the creation of the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy in 1867. He reformed the officer training program and laid the foundations of an armored fleet.

Baron Friedrich von Pöck, Tegetthoff’s successor, had even more problems securing financial resources for naval expansion when Italy joined the Triple Alliance in 1882. One significant development during Pöck’s tenure in the 1880s was the evolution of the torpedo boat and interest in torpedo tactics. In the decade before World War I, Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli’s naval expansion program had a great influence. He gained support for his plans from influential businessmen as well as Archduke Francis Ferdinand, but naval expansion took considerable resources that otherwise would have gone to the army.

Following the example of Admiral Tirpitz in Germany, Austria-Hungary joined the naval race because no one expected that Italy would renew the Triple Alliance in 1912. In response to the Italian dreadnought program, Vienna built its own dreadnoughts. By 1914 the Austro-Hungarian navy included three dreadnoughts, three semi-dreadnoughts, and six pre-dreadnoughts. Montecuccoli successfully disarmed traditional Hungarian opposition to naval expansion by granting contracts to Hungarian factories and significantly increasing the proportion of Hungarians in the naval officer corps. Even though it was a surprise when Italy renewed the Triple Alliance in 1912, tensions within the alliance increased, especially between Italy and Austria-Hungary, because of the Italo-Turkish War.

During World War I, aside from some daring raids, the Austro-Hungarian navy largely confined itself to remaining in a defensive posture in the Adriatic, displaying a classic example of the value of a fleet-in-being. After the imperial navy inflicted serious losses on Allied supply vessels and sank a few warships along the Balkan coastline early in the war, the Entente set up a blockade at the Straits of Otranto to deny Austro-Hungarian vessels access to the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, German and Austrian submarines successfully slipped through the blockade throughout the conflict and sometimes even surface vessels made it through the line of Entente ships.

Admiral Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya gained renown in early May 1915 in a daring sortie when, in command of the cruiser Novara, he towed a German submarine to open water, well behind the Allied line. In May 1917 he led an attack against the Allied drifters. This Battle of the Otranto Straits ended in an Austro-Hungarian victory but brought an expanded Allied naval presence at the bottleneck of the Adriatic, which denied success to future Austro-Hungarian attempts.

More active was the naval war within the Adriatic between the Italian and the Austro-Hungarian navies after Rome joined the Entente side in April 1915. While smaller Austro-Hungarian warships successfully bombarded the unprotected Italian coasts, the Italian navy achieved successes in deploying fast motor torpedo boats. Speed and surprise rather than firepower and size mattered in this Adriatic guerrilla war.

The defeat of the Central Powers in World War I brought an end to the Austro-Hungarian navy. Mutinies became more frequent in the navy after late 1917, even though Horthy, the new commander, did everything possible to prevent the disintegration of the fleet by keeping his men and ships active. When the Balkan Front collapsed in September 1918, the fleet was in a state of disarray. To prevent further bloodshed, Emperor Charles agreed to the turnover of the navy to the newly created Yugoslav state. Admiral Horthy administered the transfer of the fleet on 31 October 1918.

References

Greger, René. Austro-Hungarian Warships of World War I. London: Allan, 1976.

Halpern, Paul G. The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1914–1918. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Sakmyster, Thomas L. Hungary’s Admiral on Horseback: Miklós Horthy, 1918–1944. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Sondhaus, Lawrence. The Habsburg Empire and the Sea: Austrian Naval Policy, 1797–1866. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1989.

———. The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1994.

Vego, Milan N. Austro-Hungarian Naval Policy, 1904–1914. London: Frank Cass, 1996.

Horthy de Nagybánya, Miklós (1868–1957)

Hungarian officer in the Austro-Hungarian navy and regent of Hungary, 1920–1944. Born on 18 June 1868, at Kenderes, Hungary, Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya entered the Austro-Hungarian Naval Academy at Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia) at age 14. Despite his Calvinist Hungarian background, Horthy progressed quickly in his naval career and became aide-de-camp in the Catholic Austrian Emperor Francis Joseph’s court.

Horthy gained renown in the Adriatic theater of World War I. He first distinguished himself in early May 1915 during a daring sortie when he commanded the cruiser Novara and towed a German submarine to open waters, well behind the line of enemy ships. Others followed his example, which considerably increased Central Powers submarine activities in the Adriatic and the Mediterranean. In the Battle of Otranto Straits (15 May 1917), Horthy led a raid against the Allied naval barrage that sealed off the Austro-Hungarian navy from the Mediterranean. Although damage to the blockading ships was considerable, the attack was more important from a psychological point of view in a time of frustration born from inactivity. The “Hero of Otranto” then commanded the dreadnought Prinz Eugen. Disappointed by a wave of mutinies, in March 1918 Emperor Karl I replaced Admiral Maximilian Njegovan with Horthy as commander of the fleet. In the process Horthy bypassed 48 more senior officers.

Rear Admiral Horthy was able to maintain the integrity of the navy even as the dual monarchy was disintegrating. He conducted regular maneuvers and gunnery practice to keep morale high. On 8 June 1918, Horthy attempted to repeat the success of his 1917 raid against the Entente blockade, but the loss of the dreadnought Szent István forced him to abort the mission. He largely succeeded in maintaining discipline in the fleet, despite the overall military failure. After the collapse of the Balkan front and creation of an independent Yugoslavia, Karl I instructed Horthy to hand over the fleet to the Yugoslavs, which he did on 31 October 1918.

Horthy’s postwar career took a sharp political turn. After a brief period of inactivity on his estate, he joined counterrevolutionary forces opposing Béla Kun’s short-lived Soviet Republic. Horthy commanded the National Army, a detachment of 5,000 Hungarian officers of the former Austro-Hungarian army. When the Communist government collapsed, Horthy’s force remained the single Hungarian armed force in the country; this led to his appointment as regent of Hungary.

Horthy subsequently established an authoritarian regime that fought off Karl I’s attempts to return to the throne, as well as progressive forces that tried to make Hungary into a parliamentary democracy. To obtain international help for the return of the vast territories lost at the end of World War I, Horthy and his governments of the 1930s established a close relationship with Hitler’s Germany, which later swept the country into World War II on the Nazi side. When Horthy attempted to break away from the German alliance in the face of certain defeat in October 1944, the Germans deposed him and installed a fascist puppet government. Horthy died in exile in Estoril, Portugal, on 9 February 1957.

References

Halpern, Paul G. A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994.

Sakmyster, Thomas L. Hungary’s Admiral on Horseback: Miklós Horthy, 1918–1944. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Sondhaus, Lawrence. The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1994.