March 23 1953

In the I Corps sector, 7th Division zone, the Chinese mount strong attacks to evict the U. S. 7th Division from three outposts, Hills 255, 191 and 266, the latter receiving the biggest thrust of the assault. At Hill 255, known as Pork Chop Hill, and at Hill 191, the Chinese are repulsed. At Hill 266 (Old Baldy), de fended by elements of the Colombian Battalion, the first wave of Chinese steam-rolls into the positions at about 2100 and seizes the objective. The Colombian troops withdraw to the southeastern slope. On the following day, the 7th Division mounts a counterattack and fights its way to the crest, where a tenacious brawl erupts. The Chinese, however, retain the bunkers and trenches. The elements of the 7th Di vision are compelled to disengage. A new counterattack is mounted on the 24th, but again, the Chinese prevail. The Chinese gain one of the three hills, but in the process, according to the records of the U. S. 7th Division, they sustain about 750 casualties. At Hill 191, the fighting is of short duration. The de fenders request assistance while the enemy battalion begins its ascent. The reinforcements arrive to bolster the line and force the Chinese to abort the attack soon after it had begun. In the meantime, at Hill 255, another battalion launches an attack and, bolstered by tanks and artillery, the Chinese succeed in gaining the summit. The elements of the 7th Division are forced to withdraw about 700 yards, but by midnight, a counterattack unfolds. Slightly after midnight (23rd-24th), the 7th Division contingent initiates a charge that carries them to the summit, where they eliminate or disperse the Chinese to reclaim the hill.

April 16-18 1953

In the X Corps sector, 7th Division zone, at about 2200, the Chinese launch an attack against Hill 255 (Pork Chop Hill), defended by elements of the 31st Infantry Regiment. The Americans number less than 100 troops, but they attempt to hold against a tenacious charge. Communications fail; however, through the use of flares, they receive support from the artillery. Nevertheless, the artillery is able only to delay the assault. Once it ceases, the Chinese resume the relentless attack and by 0200 on the 17th, the enemy controls much of the hill and the defenders are totally isolated. Reinforcements mount a counterattack at 0400 and are able to reach the positions of the defenders, but afterward, the combined strength is insufficient to regain the lost ground.

Subsequent to dawn, the Chinese move to eliminate the Americans; however, the survivors, about 55 troops, defiantly hold their positions in the high ground. The real estate encompassing the outpost suddenly becomes of great value, as Eighth Army concludes that it must not fall to the Communists to prevent them from boasting of a victory at Panmunjom. At 2100 on the 17th, two companies of the 17th Regiment move out to evict the Chinese and rescue the men at the outpost. The Chinese, holding the western tip of the hill, are not greeted by whistles and bugles; rather the cold steel of the attack ing force, which simultaneously strikes from two sides to ignite a furious battle that continues into the following day.

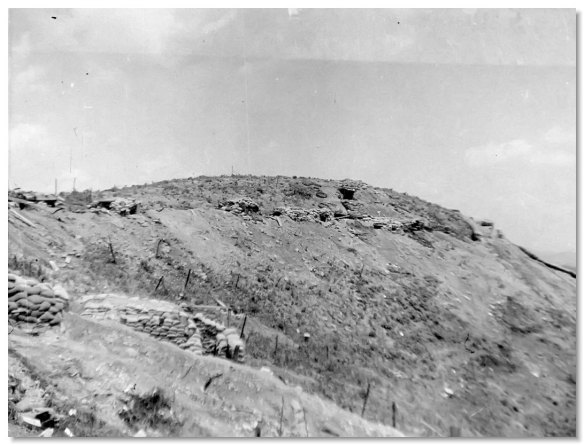

Pork Chop Hill, already deeply scarred from heavy fighting, becomes a cauldron, as neither side is willing to concede the ground. Both the Americans and the Chinese pour fresh troops into the day-long donnybrook, but by about dusk, the Americans prevail as the Chinese retire, leaving the Pork Chop under American control. The Chinese, however, continue to hold Hill 266 (Old Baldy) and from their positions, they are able to maintain surveillance of Pork Chop Hill. The hill is fortified soon after the Americans regain control and the Chinese continue to attempt to retake it. Like several other hills that have been gained, lost and regained at high cost, Pork Chop Hill is abandoned by the Americans during July.