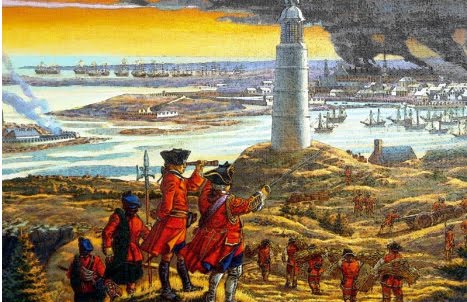

Capture Of Louisbourg 1758.

Loudoun plans attack of Louisbourg

Desperate to undertake some offensive action against the French, Loudoun began planning a huge military campaign for 1757. He decided to attack Louisbourg, an important port city on Cape Breton Island, along the Atlantic coast of New France. If the British captured Louisbourg, they could continue down the St. Lawrence River to attack Quebec and Montreal. Loudoun knew that his plan left the northern frontier of the colonies exposed to attacks by France, but he decided to move forward anyway.

Loudoun had spent the winter of 1756-57 improving the systems for collecting supplies and transporting them around the colonies. He also started recruiting colonial soldiers in small companies instead of large regiments so that he could mix them more easily with British Army units. Finally, Loudoun placed an embargo (a government order that prohibits commercial ships from entering or leaving a port) on the Atlantic coast in an attempt to stop illegal trading with the French in Canada and the West Indies. Only military ships were allowed to come and go in port cities from Maine to Georgia. At first, the colonies willingly obeyed Loudoun’s order, believing that it would be a temporary war measure. As the embargo continued for months, however, it began to cause hardships for merchants and farmers who needed to send or receive goods from overseas markets. Over time, people in the colonies came to resent the commander-in-chief. They felt that he did not care about their welfare. Eventually, the colonial governors forced Loudoun to reopen the ports by refusing to supply his army.

Loudoun set sail for Louisbourg from New York on June 20. He took along a force of six thousand men on one hundred ships, making it the largest expeditionary force ever to set sail from an American port. Loudoun’s forces arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, ten days later. They waited there another ten days until a Royal Navy squadron (group of ships) came to escort them. Before the attack could begin, however, the Royal Navy wanted to find out how many French Navy ships they would face in Louisbourg. Finally, on August 4, a scout ship returned to report that the French had a huge fleet of three squadrons in Louisbourg. Since it was too late in the summer to bring more Royal Navy squadrons to the area, Loudoun decided that there was no way his mission would succeed. He reluctantly called off the attack and ordered all the ships to return to New York.

French destroy Fort William Henry

Around the same time as Loudoun left for Louisbourg, he sent fifty-five hundred colonial troops and two regiments of British Army regulars under General Daniel Webb to defend the northern frontier in New York. One of the main British strongholds in this region, Fort William Henry, located at the south end of Lake George, had been damaged by a surprise attack in mid-March. A force of fifteen hundred French, Canadians, and Indians under François-Pierre Rigaud had destroyed several outbuildings as well as some boats and supplies. Although the British had turned back the attack, it had left the fort vulnerable to further attacks via water.

As it turned out, the French were planning a major offensive against Fort William Henry. The series of French military successes over the previous two years-including the defeat of Braddock and the capture of Fort Oswego-had attracted the attention of many Indian nations. The French were able to recruit two thousand warriors from thirty-three different nations to take part in the attack of Fort William Henry. Montcalm brought the Indians, along with six thousand French regulars and Canadian militia, to Fort Carillon at the north end of Lake George.

Defending Fort William Henry were fifteen hundred men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Monro (c. 1700-1757), an aging officer who had never served in the field before. In late July, Monro heard a rumor that eight thousand enemy forces had gathered across the lake from his position. He sent five companies of colonial troops across the lake by boat to check out the rumor, but the British boats were ambushed by five hundred Indians and Canadians. Only four of the twenty-two British boats escaped the trap, and three-quarters of the men were killed or captured. General Webb was making his first visit to Fort William Henry when the survivors straggled back to safety. He retreated to Fort Edward and sent back one thousand reinforcements to help Monro hold the fort.

On the morning of August 3, the British and colonial defenders saw 150 Indian war canoes and 250 French bateaux (small, flat-bottomed boats) coming toward them across the lake. The boats carried sixty-five hundred men and some artillery. Monro knew that Fort William Henry could not withstand artillery fire for very long. He needed troops from Fort Edward to attack Montcalm’s forces before they finished setting up the artillery. But Webb refused to send any more troops, deciding that he needed them to defend Fort Edward.

Over the next few days, Fort William Henry was battered by enemy shells. The French used European siege tactics, which involved moving their guns ever closer to the fort. On August 9, Monro was forced to surrender the fort. In his efforts to conduct the war in a civilized manner, Montcalm negotiated honorable terms of surrender with the British forces. He allowed the men to keep their personal possessions and march to Fort Edward, as long as they promised not to fight against the French anymore. Once again, however, Montcalm had failed to consider his Indian allies when making the deal.

“Surrender of Fort William Henry, Lake George, N.Y. 1757.”

Angry at being left out of the settlement, the Indians became determined to take the trophies they felt they had earned. What followed has been called “the massacre of Fort William Henry.” As the British forces gathered their wounded and began marching toward Fort Edward, they were brutally attacked by the Indians. Up to 185 men were killed and between 300 and 500 were taken prisoner. Montcalm was horrified at this turn of events. He tried to use his French troops to force the Indians to give up their captives, but the Indians responded by killing the prisoners so that they would have a scalp as a trophy. Once they were satisfied with the trophies they had collected, the Indians slipped into the woods and headed for home.

Over the following days and weeks, Montcalm continued trying to retrieve the British prisoners by paying ransom to the Indians. He knew that his honor was at stake, since he had failed to live up to his end of the surrender agreement. He also worried that the incident would make British leaders less willing to negotiate if they captured French forts in the future. About two hundred prisoners were recovered through Montcalm’s efforts, as well as those of Vaudreuil in Montreal. In the meantime, British survivors trickled into Fort Edward for a week after the battle. Their stories created strong feelings against the French and the Indians among British leaders and the American colonists.

The incident at Fort William Henry turned out badly for the Indians as well. The British forces defending the fort had been suffering from smallpox (a disease caused by a virus), which the warriors carried back to their people. It created a terrible epidemic among the western tribes that caused a great deal of suffering and death. Between the smallpox epidemic and Montcalm’s actions in negotiating a surrender-which the Indians viewed as a breach of trust-the Indians never turned out in support of the French in such great numbers again.

Following his victory, Montcalm destroyed Fort William Henry and returned to Fort Carillon. He chose not to attack Fort Edward, located a short distance to the south along the Hudson River. After all, most of the Indians had already left, and many of his Canadian troops needed to return home to harvest their crops. Still, the capture of Fort William Henry left the British in a vulnerable position. Only little Fort Edward stood between the French and several important targets, including the trading center of Albany and New York City itself.