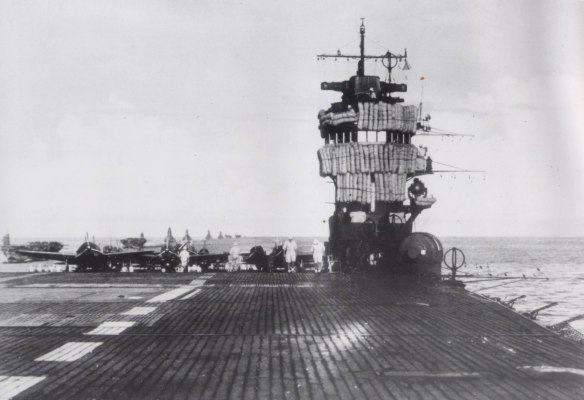

Akagi leaving Celebes Island for the attack on Colombo, 26 March 1942. In the background are other carriers and battleships of the carrier striking force.

Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi in April 1942 during the Indian Ocean Raid as seen from an aircraft that has just taken off from her deck.

A Grumman Martlet fighter about to be catapulted from the flight deck of HMS Formidable.

British heavy cruiser Cornwall, on fire, listing, and sinking after being attacked by Japanese aircraft. Sister ship Dorsetshire was also sunk in this same attack.

British carrier Hermes sinking after taking at least 40 hits when being attacked by Japanese naval aircraft.

Beginning in February 1942 when boats formerly operating off Hawaii and the American West Coast were added to the mix, the Japanese submarine command rushed its units into the Indian Ocean, where they promptly sank nearly eighty-three thousand tons of Allied merchant shipping at almost no cost. In early April, Kido Butai, minus Kaga, sent home for repairs, entered the Indian Ocean in order to neutralize whatever British sea power and airpower remained on the western flank of Japan’s new Southeast Asian empire. Thousands of miles away, the American battle fleet remained smashed in the mud of Pearl Harbor, while the handful of U.S. carriers had begun hastily devised “pinprick” attacks on the eastern and southern perimeters of Japan’s imperium.

The British Admiralty, meanwhile, had hastily assembled a new “Eastern Fleet” in the waters near Ceylon (Sri Lanka) under Admiral James Somerville. On paper the fleet looked powerful enough: battleship Warspite and no fewer than four sisters of the Royal Sovereign class, plus two large modern carriers, Indomitable and Formidable; the old and small carrier Hermes; seven cruisers; and sixteen destroyers. But the force was much weaker than it seemed. The battleships, all veterans of Jutland, were poorly armed against antiaircraft attack and were known to be floating coffins. Hermes could deploy only a dozen obsolete fighter aircraft, while the two big carriers together embarked only fifty-eight slow biplane strike aircraft and thirty-three fighters of markedly inferior quality. The fighters could be wiped out in either the strike-escort or combat–air patrol mode by Nagumo’s fast and nimble Zeros, and the biplanes would be easy prey should they try to attack the Japanese task force. Once a British carrier strike was brushed aside, Nagumo’s superb torpedo planes and dive-bombers could go after the Eastern Fleet with impunity, and Somerville knew it. Not only were his battleships vulnerable to air assault, but so were his carriers. Built to withstand extensive bomb hits and to survive even devastating damage above decks, the Illustrious class had not been provided with similar protection against torpedoes. Indomitable “nearly sank after being hit by a single aircraft-launched torpedo in the Mediterranean in 1943.” Its sister Formidable was doubtless just as fragile, while Hermes had no protection at all.

Even before Nagumo appeared, Somerville had made the decision to employ his venerable and vulnerable vessels merely as a “fleet in being.” When Kido Butai devastated Ceylon and sank two British heavy cruisers and Hermes, Somerville, in a complicated series of maneuvers, evaded battle and then withdrew temporarily all the way to Mombasa in East African waters, while a small enemy task force under Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, built around the light carrier Ryujo, raided the Indian coast in the Bay of Bengal, destroying twenty-three merchant ships and leaving Indian coastal trade paralyzed for weeks.

Churchill was in despair. There seemed no way to stop the Japanese from dominating the entire Indian Ocean basin. On April 7 the prime minister wrote President Roosevelt that five and possibly six Japanese battleships—two or more armed with sixteen-inch guns that could blow the Royal Sovereigns to pieces— were lurking near Ceylon in company with Nagumo’s carrier task force. Somerville’s fleet would surely be overwhelmed in any battle with the enemy who had just completed the first of what would be two shattering air raids against the island. “The situation is therefore one of grave anxiety,” and the prime minister begged the president to order some sort of demonstration by the U.S. Pacific Fleet (which “must now be decidedly superior to the enemy forces”) in the Indian Ocean. Roosevelt, of course, could offer nothing, and Churchill arranged to land a hastily gathered invasion force on the northern tip of Madagascar, convinced that the Japanese were coming that way.

A young American naval officer who had escaped the cauldron of the Philippines expressed the attitude of perhaps exaggerated respect that unprepared Western Allies came to hold for their Oriental enemies in those first desperate months of the Pacific war when Nagumo’s Kido Butai was running wild:

Nobody knows anything about a war until it begins. Just two years before the Polish air force had been blown to hell on the ground. The French caught it the following spring. In spite of that, the same thing happened to our planes at Pearl Harbor. And yet two days later, in spite of all of it the Japs catch our air corps [at Clark Field] on Luzon with its pants down. Only that wasn’t the end. Months later, on my way out through Australia, I pass a big American field, and there they are, bombers and fighters parked in orderly rows, wing tip to wing tip. “Hell,” they told me, “The Japs are hundreds of miles away.” Except that’s where they’re always supposed to be when they catch you with your pants down, and I thought to myself, Jesus Christ, won’t these guys ever learn?

LINK