Turkey, heart of the Ottoman Empire, had joined the Central Powers in October 1914.Through a combination of botched diplomacy, neglect, and underestimation of the ability of Turkey to put up much of a fight, leaders in England and France rather suddenly found themselves confronted with a new set of major problems growing out of the Turkish decision. If the Ottoman Empire attempted to send its massive but ill-equipped army to reclaim its jurisdiction over Egypt, the Allies could lose the vital Suez Canal link between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

More imminently, Turkey controlled access to the Black Sea, where Russia had its only ice-free ports in winter, through the waterways connecting to the Mediterranean Sea. The Bosporus flowed as a narrow but unbridged waterway dividing Europe from Asia at the city of Constantinople, then the capital of the Ottoman Empire. That waterway passed south to the Sea of Marmara, enclosed by land in the 100-mile-long neck known as the Gallipoli Peninsula, where the water again narrowed in the Dardanelles passage (itself 38 miles long), before emptying into the Mediterranean. With ships, minefields, and shore-mounted artillery, the Turks found it quite easy to monitor all water-borne traffic and to prohibit the passage of any enemy warships or merchant ship traffic. With the Ottoman declaration of war, Turkey suddenly cut off the traditional Black Sea ports of Russia from Allied traffic. By closing the single strategic choke point of the Dardanelles passage, Turkey could prevent supplies from the Allies ever reaching Russia. Some of Russia’s other ports were icebound in winter, and the Pacific port of Vladivostok, although linked by rail to European Russia, offered a very poor substitute for the Black Sea ports closed by the Ottoman decision.

The Turkish threat to the Suez Canal seemed only slightly less imminent. Turkey had nominal rule over Egypt, although British troops had occupied that region since the 1880s to help guarantee British and friendly access through the canal, one of the world’s most crucial maritime choke points. If Turkish troops in nearby Palestine, then under Ottoman rule, marched across the 120-mile-wide Sinai Peninsula and closed the canal, the Central Powers could effectively block the best route for transport of troops from Australia, New Zealand, and India to assist Britain in Europe. The lightly manned garrison in Egypt had to be immediately strengthened against this very real threat.

Despite the strategic importance of the Ottoman Empire, with its ability to control these crucial waterways, policy makers in Britain and France and the public in those countries tended to think that any battles fought against the Turks would represent a “sideshow.” Western Europeans often jokingly spoke of the Ottoman Empire as the “sick man of Europe” for its ineffectual control of the Balkans and its losses of territory to smaller nations like Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria during the 1912–13 First Balkan War. The Ottoman acquiescence in the British occupation of Egypt, coupled with the seizure of the North African territory of Libya by Italy in 1911, all seemed to suggest that the empire verged on collapse and that its remaining territories would readily fall as spoils of war to the victors. Such expectations also rested on a racist view that Turks could not possibly stand up against British or other European troops. This illusion, in particular, died hard.

In Britain, some saw Turkish weakness as an opportunity. Winston Churchill, serving as First Lord of the Admiralty, believed that a British naval expedition to force the Dardanelles and take Constantinople could quickly open the way to aiding Russia and allow encirclement of the Central Powers. This concept would grow into a somewhat muddled plan to take the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli Peninsula, subdue Constantinople, and knock the Turks out of the war quickly.

The battles of World War I fought in the Middle East turned out not to be a sideshow at all, but rather a series of grand engagements that shaped the history of the region for the rest of the 20th century and left a legacy of lessons about how warfare would be fought in the new era. World War I in the Middle East revealed the difficulties of mounting a major invasion of troops from the sea and showed how out of date the traditional tactics of war had become. It also showed how a racial holocaust could transpire during a major war. And, in a lasting legacy, it left behind redrawn maps of the region that sowed the seeds of conflict for at least a century.

DISASTROUS LESSONS

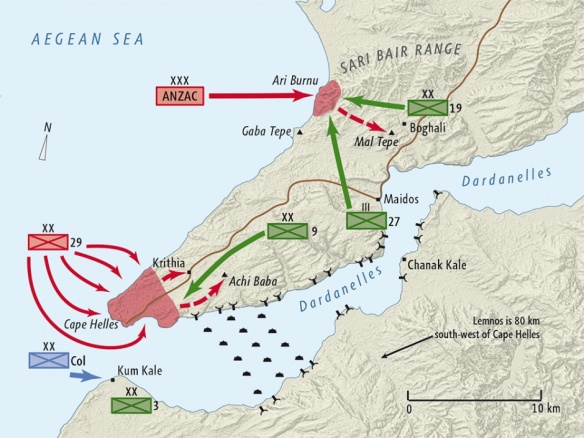

The effort against the Dardanelles and the landings of troops at Gallipoli led to more than 250,000 Allied casualties, and demonstrated many of the problems of coordinating army and navy forces in “combined operations.” A Royal Commission in Britain reviewed the mistakes almost immediately, and, over the next decades, a host of published studies dissected the campaign. The commission reviewed and studied every detail of the failed operation, from chain of command, to personality of officers, tactics on the ground, supply systems, and use of aircraft, ships, and submarines. Although the Allies made many mistakes, in some cases they simply suffered the bad luck of the accidents of war. In retrospect, the history of Gallipoli became one of the great tragedies of World War I.

While the great powers in western Europe engaged in war, Turkey unleashed a massive genocidal holocaust against the Armenian population of Turkey. At first, journalists and neutral diplomats like those connected with the American legation assumed the Turkish authorities simply wanted to repress any political dissent among the Christian Armenians who might feel more sympathy for the Russians than for their Muslim government. Such observers could not believe the early accounts of the horrors of extermination of the civilian population. However, before the slaughter subsided, upwards of 1 million Armenian civilians had been viciously murdered. This mass atrocity in itself served as a precedent, in several ways, for the later holocaust against the Jewish people conducted by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and under the cover of World War II. From the perspective of potentially victimized minority ethnic groups around the world, the Armenian tragedy far exceeded in importance the military defeat of the Allies during the Gallipoli campaign.

As the British attacked at Gallipoli, defended the Suez, and invaded the Mesopotamian provinces (now the nation of Iraq) of the Ottoman Empire, they came to realize that the Turkish army, although ill-equipped and although defeated in the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, put up a formidable fight, especially when on the defensive. In fact, the principles that produced stalemate on the western front also served to stymie British and French advances at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia short of Baghdad, and in the British effort to advance from the Sinai Peninsula through Gaza into Palestine. Entrenching shovels and the machine gun proved as effective in the hands of the Turks as in the hands of the French and Germans on the western front. The theory of massed attack by troops against defenders, inherited from the age of Napoleon, worked no better in the Middle East than it had in Europe. That method of war seemed equally disastrous at Gallipoli, on the Tigris River in Mesopotamia, and in Palestine. Although most Allied officers failed to learn that lesson during the war, a few did.

The war against the Ottoman Empire left the legacy of a completely changed map of the Middle East. The British, in this region as well as in Europe and the Far East, worked to gain allies by making secret promises of territorial adjustment. That concept might have been reasonable, except for the fact that in the Middle East the British made at least three separate contradictory groups of promises—to the French, to leaders of the world Jewish community, and to the Arabs. The British partially fulfilled other promises to the Russians, Italians, and Greeks, while assurances to the Kurdish people vanished into history. As the Allies cut up the Ottoman Empire and occupied parts of it in the postwar world, those contradictory promises would come back to haunt the British and would sow the seeds of future conflicts that would last into the 21st century. Many of the burning issues that occupied headlines in later decades, such as the status of Palestine and Israel, the nature of Iraqi nationality, and the relationship of Arabic- speaking states with Europe and the West, had their origins in the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. What seemed to the Arabs and even to British critics of the policy to be duplicity probably resulted from the fact that different statesmen and officers made various promises at different times. In that way they created a muddle of affairs not fully known until after the war when all the commitments began to surface.