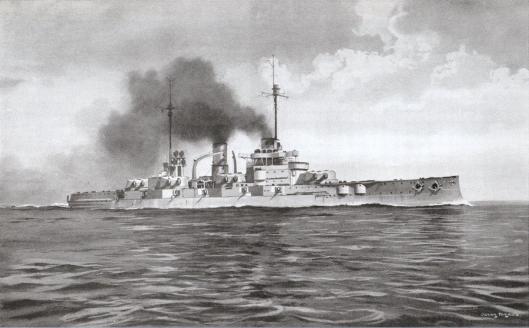

Germany’s first dreadnought-type battleships were the Nassau class (Nassau, Westfalen, Rheinland, and Posen, completed in 1910). These warships represented no great advance over Dreadnought, but the German Navy did enjoy certain areas of distinct superiority over its RN rival that would persist through World War I. All four Nassaus fought at Jutland. The following Helgoland class (Helgoland, Ostfriesland, Thuringen, and Oldenburg, completed 1911–1912) were improved Nassaus and also fought at Jutland, as did the succeeding Kaisers (Kaiser, Friederich der Grosse, Kaiserin, Koenig Albert, and Prinzregent Luitpold, completed 1912–1913). These German battleships pioneered super-firing guns and were the first with turbine drives (only one German firm could manufacture large turbines, and von Tirpitz at first reserved its products for his cruisers). Oddly and uniquely, their super-firing turrets were mounted aft only (leading to some British jokes about the Germans taking pains to cover themselves in retreat).

The last class of German battleships to fight during World War I were the Bayerns (Bayern and Baden, completed in 1916; two sisters were uncompleted by war’s end). These were the first German battleships to mount 15-inch guns, and they each carried three oil-burning boilers. The remaining 11 boilers were still coal-fired, although oil could be sprayed over the coal to aid combustion. Although neither completed unit was finished in time for Jutland, Baden did have an adventurous career: It set out on 18–19 August 1916 against British coastal targets but was nearly cut off by the Grand Fleet; it sortied in the North Sea two months later, then bombarded Russian shore targets in the Baltic Gulf of Riga in the month of the Russian Revolution (October 1917); and it participated in the fruitless High Seas Fleet sweep toward the Norwegian coast in April 1918. Beached by British crews at the Scapa Flow seppuku, Baden was carefully examined by RN constructors. Its construction was found to be in no significant way superior to contemporary RN battleships. (Baden was expended as a target ship in 1921.)Named after its creator, Alfred von Tirpitz, and related to the contemporaneous notion of Weltpolitik of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Tirpitz plan called for an ambitious expansion of the German Imperial Navy. The term Tirpitz Plan was not in use at the time it was conceived in the late 1890s. Rather, its full dimensions emerged 60 years later when the files of the Reich Navy Office became available to researchers for the first time. These files had been held under lock and key by the German navy after World War I until they were captured by the Allies in 1945 and housed uncatalogued in Cambridge, England. After their return to West Germany in the 1960s, scrutiny of the massive holdings revealed a program for the expansion of the Imperial Navy that was much more ambitious than earlier scholarship had assumed.

There was, to begin with, a highly technical side to the Tirpitz Plan. In a narrow sense it was concerned with the replacement of older ships and the building of additional new ones. Toward this end, Tirpitz and his team of naval officers arranged, as a first step, the older battleships and cruisers in such a way that they came up for replacement in a sequence of two per annum. If, because of an earlier building tempo, more than two came up, the replacement would be stretched so as to secure a regular tempo of two ships.

However, Tirpitz’s ambition was to launch three ships per annum. Accordingly, one new ship was added to the two replacements, resulting in what came to be called an annual “3-tempo.” These three ships were then to be replaced again after 20 years, producing in the meantime a fleet of 60 big ships. There were two considerations behind this systematic design not revealed in Tirpitz’s First Navy Law of 1898. First, this law stipulated that those 60 ships were to be automatically replaced after 20 years, so that the start of the renewal cycle in 1918 would not require any further budgetary approval by the Reichstag. Second, it provided funding for only three years, 1898–1900, and the Reich Navy Office kept silent about the intention to introduce a second bill in 1900 that would extend the 3-tempo for a further four or five years. After that period more bills were to be submitted until 1918 when the gap would be filled with the building of three battleships per annum.

Because the deputies were not told in 1898 and 1900 that there were more bills to come to extend the 3-tempo all the way until 1918, they also did not appreciate that the 20-year replacement rule in the 1898 law was intended to deprive them of their budgetary powers over the navy. This means that in 1918, Tirpitz would have been independent of the vagaries of the Reichstag approval process. The navy of 60 big ships would be replaced automatically and hence be at the disposal, without interference from the democratically elected assembly, of the monarch who was in exclusive charge of German foreign policy.

Apart from this antiparliamentary calculation, the Tirpitz Plan to expand the Imperial navy in several stages to a total of 60 battleships in 20 years was also adopted with Britain in mind. If London had realized from the start that the kaiser aimed to have all those ships, the British would have been so alarmed that they would have tried to “outbuild” the Germans. Because of the initially veiled German buildup in stages, they recognized rather belatedly what Tirpitz was planning, but when they did, they engaged Germany in a naval arms race that began in 1905–1906.

This plan to establish a 3-tempo over 20 years with its cool antiparliamentary and anti-British considerations emerge clearly from the memoranda and tables that the Reich Navy Office drew up at the turn of the century. Not familiar with this material, historians in the early post-1945 period believed that the strengthening of the navy had a purely defensive purpose to protect the country’s overseas interests and colonies at a time when other great powers were also building ships. Others have seen the systematic planning in the Reich Navy Office as part of a bureaucratic power struggle in which Tirpitz, as navy minister, tried to assert himself against the high command, in charge of war planning, and the admiralty staff, responsible for personnel policy. Here Tirpitz is seen as a skillful administrative infighter in a struggle that also revolved around the question of whether the German fleet should consist of cruisers or battleships.

The third position argues that Tirpitz was a very political officer who, with his program, pursued two major long-term objectives. The first one was, as already indicated, to liberate the Imperial navy from the shackles of budgetary approval by the Reichstag and to achieve an “iron budget” that could not be reduced. Here the army was the model. After 1918, only further additions to the fleet of 60 ships could be voted on, and calculations have in fact survived in the files that show an increase in the 3-tempo to four ships per annum. The German army had a similarly untouchable budget.

Apart from its domestic role, however, the Tirpitz Plan also had a veiled foreign policy angle. Once completed, the 60-battleship fleet was deemed by Tirpitz and his advisers to be powerful enough to defeat the Royal Navy in a do-or-die battle in the North Sea; for they had also reckoned that over the next 20 years, London would not be able to build more than 90 ships. Naval doctrine of the time assumed that a fleet with a one-third inferiority had a genuine chance of defeating an opponent, provided the latter was the attacker. If this attack ever came, Tirpitz hoped to defeat the Royal Navy in their home waters. Britain would then have lost its dominant position in the world in one bold stroke. If, on the other hand, London sat tight, Tirpitz expected the 60-battleship fleet to provide the kaiser with the diplomatic leverage to extract concessions at the conference table when it came to the much-vaunted “redistribution of the world” in the twentieth century. This is where the ambitions of the Tirpitz Plan became connected with those of Wilhelmine Weltpolitik.

The plan failed just as Weltpolitik did. Suspecting that the Germans were up to something sinister—that they wanted “to steal our clothes”—the British engaged the kaiser in a quantitative naval arms race, more and more ships, as well as a qualitative arms race, and bigger and bigger ships. The launching of the Dreadnought class from 1906 suddenly made Tirpitz’s existing ships obsolete. He tried to keep up by also building both more and bigger ships, but he was defeated by the escalating costs. It proved more and more difficult to persuade the deputies who, after all, still had to approve the naval budget to allocate the additional resources needed to keep up with the Royal Navy. By 1912, the original design was in disarray. The army came along and demanded the priority in defense that the navy had enjoyed in previous years. Germany returned to a continental strategy and the war that broke out in July 1914 was fought on land. Tirpitz’s navy remained idle for most of the war, and submarines became the instrument of German naval warfare.

FURTHER READING: Berghahn, V. R. Der Tirpitz-Plan: Genesis und Verfall einer innenpolitischen Krisenstrategie unter Wilhelm II. Düsseldorf: Droste, 1971; Brézet, F. E. Le plan Tirpitz, 1897– 1914: une fl otte de combat allemande contre l’Angleterre. Paris: Librairie d’l’Inde, 1998; Herwig, H. H. Luxury Fleet. London: Allen & Unwin, 1980; Steinberg J. Yesterday’s Deterrent. London: Macdonald, 1968.