The formal end to hostilities in the Pacific came while fighting was still under way in the Philippines. On 15 August 1945 almost 115,000 Japanese —including noncombatant civilians— were still at large on Luzon and the central and southern islands. One Japanese force, the Shobu Group in northern Luzon, was still occupying the energies of major portions of three U.S. Army infantry divisions and the USAFIP(NL) as well. Indeed, on 15 August the equivalent of three and two-thirds Army divisions were engaged in active combat against Japanese forces on Luzon, while the equivalent of another reinforced division was in contact with Japanese forces on the central and southern islands. On Luzon the 21,000 guerrillas of the USAFIP(NL) were still in action, and some 22,000 other Luzon guerrillas were engaged in patrolling and mopping- up activities. At least another 75,000 guerrillas were mopping up on the central and southern islands.

Tactically, then, the campaign for the reconquest of Luzon and the Southern Philippines was not quite finished as of 15 August 1945. On the other hand, the Sixth and Eighth Armies, together with supporting air and naval forces, had smashed the 14th Area Army, the organized remnants of which, slowly starving to death, were incapable of significant offensive action. The bulk of the American forces in the Philippines were already preparing for the awesome task of assaulting the Japanese home islands, and many guerrilla units were being transformed into regular formations under Philippine Army Tables of Organization and Equipment.

Strategically, the issues in the Philippines had long since been decided. The principal strategic prize of the Philippines— the Central Plains-Manila Bay area of Luzon—had been secure since early March, five and a half months before the war ended. Before mid-April American forces had possession of the most important secondary strategic prizes —air base sites from which to help sever the Japanese lines of communication to the Indies and from which to support projected ground operations in the Indies. The end of April found American forces holding virtually all the base areas in the Philippines required to mount the scheduled invasion of Japan. By 15 August base development was well along throughout the archipelago, and the first troops of a planned mass redeployment from Europe had reached the Philippines. Finally, by mid-August, few Filipinos were still under the Japanese yoke —the Allies had freed millions and had re-established lawful civilian government on most of the islands.

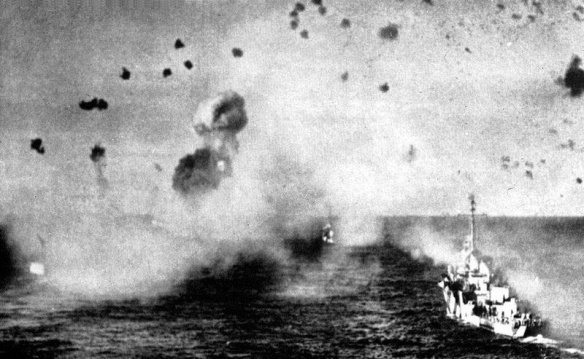

On Luzon and the central and southern islands, forces of the Southwest Pacific Area had contained or taken out of the war over 380,000 Japanese, rendering them unavailable for the defense of the homeland. The Japanese had already expended another 70,000 lives, more or less, in the defense of Leyte, where the Allies had also eliminated Japan’s vaunted naval power as a significant factor in the Pacific war. The Allies had destroyed nine of Japan’s very best, first-line divisions in the Philippines and had also knocked out six other divisions or their equivalent in separate brigades and regiments. Losses stemming directly or indirectly from the defense of the Philippines had reduced Japanese air power to the desperate expedient of kamikaze operations. If no other campaign or operation of the war in the Pacific had done so, then Japan’s inability to hold the Philippines had made her ultimate defeat clear and certain.

The cost had not been light. Excluding the earlier campaign for the seizure of Leyte and Samar, the ground combat forces of the Sixth and Eighth Armies had suffered almost 47,000 battle casualties— 10,380 killed and 36,550 wounded —during their operations on Luzon and in the Southern Philippines. Nonbattle casualties had been even heavier. From 9 January through 30 June 1945 Sixth Army on Luzon suffered over 93,400 nonbattle casualties, losses that included 86,950 men hospitalized for various types of sickness, 6,200 men injured in various ways, and 260 troops dead of sickness of injury. The bulk of the battle casualties occurred, of course, on Luzon, where the heaviest fighting took place and where the opposing forces had their greatest concentration of strength. The operations to recapture the central and southern islands cost approximately 9,060 — 2,070 men killed and 6,990 wounded. But these personnel losses cannot reflect the total cost of the campaign — the huge losses of military supplies and equipment of all kinds, together with the money and time they represented.

As usual, the Queen of Battles took the brunt of the losses. The Infantry incurred roughly 90 percent of all Sixth Army casualties on Luzon and 90 percent of all troops killed in action on Luzon from 9 January through 15 August.

The battle casualty rate was higher in other campaigns of World War II— for example, that of Third Army in Lorraine and Tenth Army on Okinawa —than for Sixth Army on Luzon, but it is doubtful that any other campaign of the war had a higher nonbattle casualty rate among American forces. For this there were many contributing factors. Men from the more temperate United States found the climate of the Philippines enervating—it was impossible for them to expend their energies at the rate they could at home, yet the demands of battle required just such an expenditure. The troops encountered new diseases, too, in the Philippines, while the contrasting hot, dry days and cold, wet nights of the mountains created obvious health problems.

Moreover, many of the units that fought in the Philippines were tired. With one exception, all the divisions committed under Sixth Army on Luzon had participated in at least one previous operation, and the majority of them had been through two. As much as a third of the officers and men of six divisions had been overseas three years; almost all the divisions and separate regimental combat teams had been in the Pacific two years. Under such conditions debilitation increased in geometric progression as Sixth Army, with the limited forces available to it, had to leave units in the line for month after month with little or no time for rest and rehabilitation.

The replacement problem also had a great deal to do with the high nonbattle casualty rate. Almost all of Sixth Army’s combat units reached Luzon understrength; none received significant numbers of replacements until April was well along. The Infantry replacements Sixth Army received from 9 January to 30 June were barely sufficient to cover the army’s battle losses—they could not cope with the problem of filling the gaps left by nonbattle casualties.

Actually, the bulk of the so-called nonbattle casualties were directly attributable to combat operations although not classed as battle casualties under the U.S. Army’s personnel accounting system. For example, an infantryman hospitalized for pneumonia contracted in the mountains of northern Luzon was as much a loss as an infantryman who was hospitalized with a wound inflicted by a Japanese rifle bullet. Combat fatigue casualties, permanent or temporary, fit into the same category.

In the sense of lessons learned, there was little new for the American units that fought on Luzon and in the Southern Philippines. As noted, all but one of the divisions had had previous experience in fighting Japanese on ground of Japanese choosing. In the reconquest of the Philippines, therefore, units applied lessons learned both in earlier combat and in training. The only really “new” type of action experienced was the city fighting in Manila, where the troops perforce made quick and thorough adjustment to different conditions of combat.

Generally, American arms and armament proved quantitatively and qualitatively superior to those of the Japanese. The only significant innovations on the American side — helicopters, recoilless weapons, and television observation of the battlefield—came on the scene too late in the campaign for complete and objective evaluation. All, however, gave promise of great things to come.

On the Japanese side, there were a few items that the American forces especially noted. Among these were the huge rockets the Shimbu Group employed in the mountains northeast of Manila. Although the rockets were generally ineffective and caused few casualties, the experience with Japanese rockets on Luzon, together with similar experiences of Tenth Army on Okinawa, portended a possibly messy situation during the planned assault on the home islands. Noteworthy also was the abundance of automatic weapons the Japanese employed. For example, to the men of the 32d Infantry Division it must have appeared that at least every third Japanese defending the Villa Verde Trail was armed with a machine gun. Also notable, if not downright surprising, was the fact that some Japanese units on Luzon proved themselves capable of employing artillery effectively. Allied forces had developed scant respect for Japanese artillery during previous campaigns in the Pacific, but those U.S. Army units that fought against the 58th IMB and the 10th Division on Luzon had a different point of view.