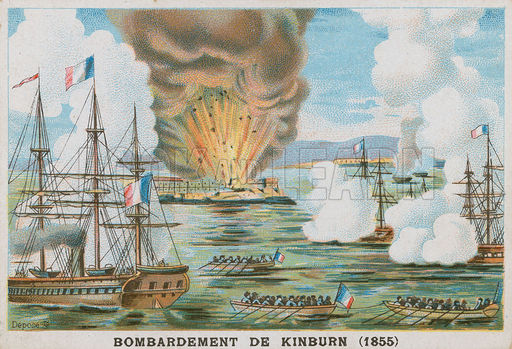

Floating Batteries at the Capture of Kinburn.

Date October 17, 1855

Location Kinburn Forts, estuary at the mouth of the Dnieper and Bug rivers, Russia

Opponents (* winner)

*French

Russians

Approx. # Troops 3 ironclad floating batteries

5 forts with 81 guns

Importance Demonstrates the superiority of ironclad warships over those of wood.

The Battle of Kinburn during the Crimean War (1854–1856) demonstrated the success of ironclad warships. In the Battle of Sinop (Sinope), on November 30, 1853, a Russian squadron destroyed an Ottoman fleet at anchor largely through the use of shells as opposed to solid shot. This led to renewed interest in iron as armor for wooden vessels. After Britain and France had entered the war, French emperor Napoleon III proposed a system of iron protection for ships, and British chief naval engineer Thomas Lloyd demonstrated that four inches of iron could protect against powerful shot.

On October 17, 1855, three French armored floating batteries, the Dévastation, Lave, and Tonnante, took part in an attack on Russia’s Kinburn Forts in an estuary at the mouth of the Dnieper and Bug rivers. Protected by 4-inch iron plate backed by 17 inches of wood, each of the floating batteries mounted 16 50-pounder guns and 2 12-pounders. They were each powered by a 225-horsepower steam engine, capable of propelling the vessel at four knots.

The Kinburn forts, three of which were of stone and two of sand, housed in all 81 guns and mortars. From a range of between 900 and 1,200 yards in an engagement lasting from 9:30 a.m. until noon, the French armored floating batteries fired 3,177 shot and shell and reduced the Russian forts to rubble. Although repeatedly hulled, the batteries were largely impervious to the Russian fire. The Dévastation took 67 hits, and the Tonnante took 66 hits. Two men were killed and 24 wounded, but these casualties resulted from two shots that had entered gun ports and another shot that had passed through an imperfect main hatch. The vessels’ armor was only dented.

At noon allied ships of the line shelled what was left of the forts from a range of 1,600 yards, and in less than 90 minutes the Russians surrendered. Undoubtedly the success of the batteries was magnified because they were the emperor’s special project, but many observers concluded that the Battle of Kinburn proved the effectiveness of wrought iron and marked the end of the old ships of the line.

References Baxter, James Phinney. The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship. New York: Archon Books, 1968. Darrieus, Henri, and Jean Quéguiner. Historique de la Marine française (1815–1918). Saint-Malo, France: éditions l’Ancre de la Marine, 1997. Padfield, Peter. Guns at Sea. New York: St. Martin’s, 1974. Tucker, Spencer C. Handbook of 19th Century Naval Warfare. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000.