Why did a civilized country follow such a barbaric leader who would unleash war and genocide? This question has troubled historians ever since. According to personal preference, explanations have ranged from apologetic references to ‘‘mass politics’’ or Marxist claims of ‘‘monopoly capitalism’’ to critical indictments of ‘‘eliminationist anti- Semitism.’’ Some scholars tend to stress that only the breakdown of the Weimar Republic gave the Nazis a chance, whereas others focus instead on the dynamics of an extra-parliamentary movement, which thrived on the resentments against the dislocations of modernity. One recent approach that seeks to reconcile the views of ideological intentionalists with the perspective of structural functionalists stresses the charismatic relationship between the leader (Führer) and his followers, a form of irrational bonding that created something like a ‘‘consensus dictatorship.’’

In contrast to the Beer Hall Putsch (1923), the Nazi seizure of power a decade later was formally legal and thus harder to resist. Although Hitler had viciously attacked the republic, he became chancellor as the head of the largest party in hopes of thereby restoring parliamentary government! The small conservative German National People’s Party offered to enter a coalition with the rabble of the Nazi mass movement, because the traditional landed and administrative elites hoped to ride the populist tiger. Because the Nazi Party had lost some of its appeal in the second 1932 election, Hitler’s initial cabinet represented only a minority—slightly more than two-fifths of the German electorate. But the liberal and democratic parties had already collapsed, and neither the Communists nor the Social Democrats dared unleash a general strike that might fail. Ironically, this initial legality was the springboard for subsequent illegality.

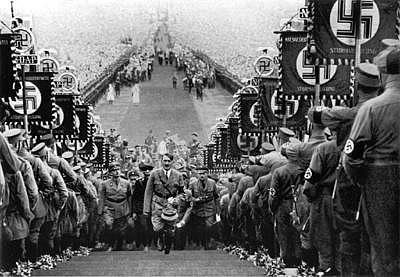

Hitler’s first priority was therefore the transformation of his limited power into a full-blown dictatorship. While a victory parade of his followers in Berlin sought to impress the masses, the storm troopers of the SA (Sturmabteilung) brutally intimidated the critics. When the fortuitous Reichstag fire (February 1933) gave the Nazis a chance to throw most Communist and some Social Democratic leaders in jail, the no longer free elections produced a slim majority of popular votes for the government. Then Hitler coerced the Reichstag into passing the Enabling Law, which suspended civil rights and gave him dictatorial command. The partly voluntary, partly coerced ‘‘coordination’’ of organizations and interest groups put Nazis in control everywhere, while censorship silenced the independent voice of civil society. Finally, the civil service purge of presumed radicals and Jews created a pliable instrument for implementing Nazi policies. The speed and ruthlessness of the ‘‘national revolution’’ rendered its opponents helpless.

The growing popularity of the Nazi regime rested largely on the recovery of the economy and on the claim of a ‘‘national community’’ (Volksgemeinschaft). Borrowing massively, the Nazis reduced unemployment by instituting a national service year, restoring the draft, initiating public works such as superhighways (Autobahnen), and, most importantly, starting a clandestine rearmament program. Though wages remained frozen, the return of full employment did increase family incomes and restored hope. After breaking the power of the trade unions, the regime proclaimed an ideal Volksgemeinschaft in which all racial comrades would be equal, thereby leveling traditional social hierarchies. The Labor Front also offered new services, such as the vacation travel of the ‘‘Strength through Joy’’ program. While opponents derided these policies as ‘‘socialism of the fools,’’ new consumption chances helped cement popular support for the Nazi regime.

Culturally speaking, the Third Reich was rather a desert, because the ‘‘flight of the muses’’ had robbed Germany of most of its creative talent. An artistic dilettante and lover of Wagnerian operas, Hitler loathed modernism and sought to purge culture of ‘‘degenerate art’’ or critical literature. Thus his ideology, presented in Mein Kampf, was a murky me ´lange of resentments against urban life, capitalism, Marxism, or the Jews. In painting, the Nazis returned to a pastoral realism with scenes of happy blue-eyed and blond-haired maidens, working in fields. Literature produced nothing better than the turgid novels of Hans Grimm, while theater was limited to presenting the expressionist plays of the aging Gerhart Hauptmann. In propaganda alone did the Nazis excel by staging the party rallies in Nuremberg and producing Leni Riefenstahl’s films. Thus hopes for a more humane Germany could survive only in exile, the concentration camps, or the Resistance.

In foreign policy Nazi Germany followed a revisionist course so as to overthrow the restrictions of the Versailles treaty. To shield rearmament, Hitler initially pursued ‘‘bread, peace, and freedom,’’ even reassuring Poland with a nonaggression treaty. But he also reintroduced the draft, remilitarized the Rhineland, and built a diplomatic ‘‘Axis’’ with Benito Mussolini’s Italy and Tojo Hideki’s Japan. His first success was the Anschluss of Austria in the spring of 1938, which incorporated the German-speaking remnant of the Habsburg Empire. Next he inflated the Sudeten German wish for autonomy into a demand for returning ‘‘home to the Reich,’’ granted by a harassed Neville Chamberlain at the Munich conference (September 1938). But Hitler underestimated the moral outrage caused by his cynical annexation of the rest of Czechoslovakia and was surprised that the West thereafter resisted his demands for concessions in the Polish Corridor and the return of Danzig. In contrast to 1914, there was no doubt that it was the Nazis who unleashed war in September 1939.

In the first half of World War II the Germans won stunning victories, surpassing anything that they had achieved a quarter century before. Nazi military strategy rested on the concept of the blitzkrieg, a mechanized lightning strike of heavy armor with mobile artillery and tactical air support that slashed through enemy lines, surrounded entire armies of defenders, and forced their surrender by spreading confusion. Because of Hitler’s personal fear of a two-front war, the Wehrmacht proceeded against one enemy at a time so as to achieve tactical superiority and use the resources of the defeated country to carry the war effort further. In this fashion he defeated Poland in September 1939, captured Scandinavia in the spring of 1940, beat France in the summer of that year, overran the Balkans in the spring of 1941, and invaded the Soviet Union thereafter. The only country able to repulse this massive onslaught was Great Britain.

Hitler’s war aims envisaged a German hegemony over Europe beyond the wildest dreams of previous nationalists. First of all, the Nazis reannexed to the Reich disputed provinces such as Alsace-Lorraine in the west and West Prussia, Poznań, and other territories in the east. Second, they created a belt of occupied areas such as Bohemia and the Polish government general, run by military governors and mercilessly exploited for the war effort. Third, Hitler’s power fantasies focused on the conquest of German Lebensraum in the east in a primitive notion that national strength rested on living space for agrarian settlements. As the ‘‘general plan east’’ stipulated, his colonial territory could be found only in Poland and Ukraine—but it needed to be cleansed of its inhabitants so that ethnic Germans could be resettled there. Finally, in reconstructing Europe the Nazis were aided by allies such as Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, and Romania and abetted by friendly neutrals such as Vichy France and Francisco Franco’s Spain.

This expansionism was inspired by a biological racism that precipitated an unprecedented genocide, now called according to biblical references ‘‘the Holocaust.’’ So as to reduce the local population to serfdom, the Slavic elite was sent to concentration camps and killed by slave labor. More radical yet was the murder of the Jews, because it sought to eradicate an entire people. In Vienna Hitler had imbibed a deep-seated racial anti- Semitism that led him from discrimination of the German Jews in the Nuremberg Laws (1935) to their persecution in the pogrom of November 1938. But only eastern victories and dreams of Lebensraum made for the quantum leap to the complete annihilation of all European Jews. Pioneered through euthanasia on the handicapped, the mass killing first proceeded through mobile death squads but was subsequently perfected through the industrial method of gassing in concentration camps such as Auschwitz, where over one million people died. Though communism might have claimed more deaths, this Nazi genocide is uniquely abhorrent because of its systematic and bureaucratic character that will darken the German name forever.

After six years of struggle, the Third Reich and its allies were finally defeated. In the long run the Nazis had no way of countering the superior manpower and industrial strength of the grand alliance between Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States. In the west, victory in the war at sea, the liberation of North Africa, and the landing in Italy were important, but not decisive. The brunt of the land fighting took place in the east, where ‘‘general winter’’ helped the Soviet Union to survive in 1941, the ferocious defense of Stalingrad in late 1942 turned the tide, and the tank battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943 established Soviet superiority. The Allied landing in Normandy (June 1944) and the air bombardment also contributed to weakening German defenses. Hitler’s fabled ‘‘miracle weapons’’ such as jet fighters and rockets and his experiments with a small atomic bomb came too late. With Berlin surrounded, the Führer committed suicide, and the Reich surrendered in May 1945.