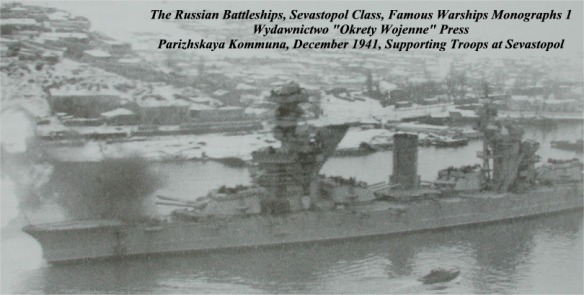

The guns of the Black Sea Fleet played a vitally important role in beating back this first German assault on Sevastopol. The battleship Paris Commune, later renamed Sevastopol, is seen in action firing her main armament, 12-inch guns.

In early August Hitler flew to Army Group Center to confer with Bock, Guderian, and Hoth. He expressed wonderment at how well operations had gone, considering the Red Army’s surprising strength, and he admitted that Army Group North might not need support from the center. Nevertheless, he again emphasized that the Ukraine and Donets Basin were essential to the Soviet Union’s economy. Interestingly, he foresaw a termination of major operations in the south by mid-September due to rainy weather and in front of Army Group Center by October. Despite the Führer’s lack of interest in Moscow, Bock stressed that only the capital offered the possibility for a decisive victory but emphasized that such a victory would require increased logistical support. Such arguments were academic because the logistical situation remained troublesome; only Guderian’s panzer group had some margin for offensive operations.

In the end, however, Hitler decided to strike at the Ukraine despite the fact that the OKH and OKW agreed (for one of the few times in the war) that German forces should concentrate on Moscow. He did concede that Army Group Center could launch an offensive against Moscow before winter, but only after Nazi forces had sealed the Ukraine and established the preconditions for capturing Leningrad.

Not surprisingly, the German advance in August was minimal. In the north, Leeb’s forces slowed to a snail’s pace; where they had averaged nearly 17 miles per day before 10 July, they now were averaging one mile. Hoepner argued that Fourth Panzer Group should withdraw from the unsuitable terrain in front of Leningrad (barely 70 miles away) and leave the city’s capture to the infantry divisions.

The heaviest fighting occurred in front of Army Group Center. In mid- July Guderian had seized the high ground around Yelnaya as a jumping-off point for Moscow. In late July and August no less than six Soviet armies counterattacked the Yelnaya and Smolensk positions, while eleven Soviet armies attacked Army Group Center’s forces from Velkie Luki in the north to Gomel in the south. Despite Hitler’s interest in the Ukraine, Guderian and his superiors argued that German troops should hold Yelnaya for reasons of prestige. Soviet attacks, often poorly executed, broke with ferocity on troops in the Yelnaya salient; motorized and Waffen SS units of Guderian’s panzer group held the ground until early August, when Fourth Army’s infantry divisions caught up.

The conditions of this battle were something the Germans had yet to experience in the war. For example, with no depth to its defenses, the 78th Division held a front of 18 kilometers with no reserves and with Soviet positions right on top of its troops. The result was heavy casualties. Within a four-day period, the division lost 400 men in an effort simply to hold its line; throughout its time in the salient, it was under constant artillery bombardment. By the time the Germans abandoned Yelnaya in early September, the battle had wrecked five infantry divisions. After the war, Marshal Georgi Zhukov claimed German casualties at 45,000 to 47,000 men, an accurate estimate.

By 1 September the Germans had suffered 409,998 casualties on the Eastern Front, out of 3,780,000 soldiers available at the beginning of the campaign. Even with replacements, combat units were short 200,000 men. More alarming was the fact that the OKH had already distributed 21 out of its initial reserve of 24 divisions to reinforce the army groups; virtually no reserves remained. The status of vehicles and mechanized units was equally alarming. Only 47 percent of the panzers were in commission; the rest were destroyed, disabled, or deadlined for repair and maintenance.

In August Kleist drove First Panzer Group down the right bank of the Dnepr east of Kiev. For the Soviet Southwestern Front, this created a dangerous situation that grew in seriousness as German forces advanced into the Dnepr bend and as Guderian’s panzer group shifted its weight against Gomel. Kiev itself held, but farther east the Germans pushed on both sides of the growing salient. As early as the end of July, Zhukov had urged Stalin to pull back; the dictator refused and relieved Zhukov as chief of staff. Stalin’s hand remained firmly on the helm. Soviet troops in the south would stand and fight where they were.

The uncertainties, if not despair, of the last days of June disappeared into a ruthless drive for survival. In mid-July Stalin had reimposed the commissar system on the officer corps. Nevertheless, the same inadequacies that had contributed to the early Soviet defeats still permeated the system. In the far north, tens of thousands of Leningraders dug anti-tank ditches to protect the city, but Soviet authorities refused to evacuate the old and young or to stock provisions for a siege. To do so would have suggested that the front might not hold and could lead directly to the firing squad. Neither soldiers nor citizens of any age could escape the draconian threats of the Soviet system.