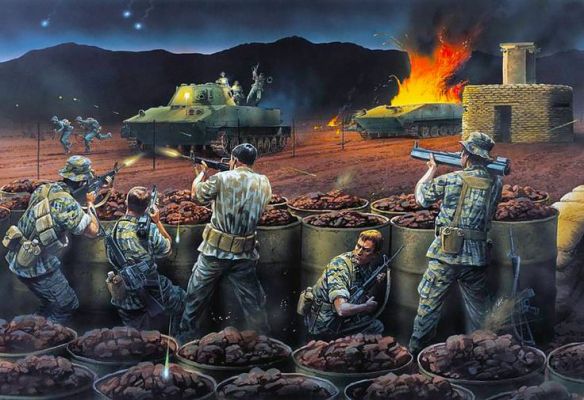

The fight for the command post, Lang Vei: The NVA tank attack on Lang Vei Special Forces Camp began at 0050 hours, February 7 with PT-76 tanks approaching from three directions: five tanks from the south, four more from QL9 from the west, and two on QL9 from the east”, Howard Gerrard & Peter Dennis

During the Tet Offensive of 1968 SFOD-A 101’s aggressive defense of the CIDG camp at Lang Vei, Republic of South Vietnam interdicted, disrupted, and attritted the 304th Regiment of General Vo Nguyen Giap’s North Vietnamese Army. The assault on Lang Vei was the first use of armor against American ground forces in Vietnam…

In early 1968, during the Tet Offensive, the North Vietnamese Army was losing the Battle for Hue and Giap thought a successful attack of the isolated Marine combat base at Khe Sanh would draw US forces away from Hue. Seizing Khe Sanh would also allow increased infiltration of NVA forces and equipment into South Vietnam from the Ho Chi Minh trail across the Laotian border. Overrunning the Marines at Khe Sanh would be a major defeat for US forces. It could be another Dien Bien Phu.

In Vietnam in 1968, Lang Vei was just one of the ten “A” camps of C Company, 5th Special Forces Group. Relatively unknown to most soldiers in Vietnam, it would soon make the front pages of Time and Newsweek. The A-team camps were normally manned by CIDG (Civilian Irregular Defense Groups) strikers, a South Vietnamese Special Forces Team (VNSF/LLDB), and a Special Forces Operational Detachment “A” Team (SFOD-A). The original Special Forces camp in that area of operations was established in Khe Sanh Village in July of 1962. However, in December of 1967, SFOD-A 101 was moved west to Lang Vei from Khe Sanh so that the Marines could occupy Khe Sanh. The first camp named Lang Vei was abandoned on 4 May 1967 after NVA regulars, aided by CIDG infiltrators, penetrated the camp’s defenses. The new Lang Vei was moved approximately 1,000 meters west and built to withstand another siege.

SFOD-A 101 moved into the camp in September of 1967 and began operations. Lang Vei was situated only 1.5 kilometers from Laos and 35 kilometers from the DMZ. It straddled Highway 9, just eight kilometers from about 9,000 Marines at Khe Sanh. Lang Vei’s mission was surveillance of the Laotian border and the DMZ, as well as interdiction of enemy infiltration routes. To accomplish this task the camp commander, CPT Frank C. Willoughby, had four under strength rifle companies of Bru Montagnards and local Vietnamese, three combat reconnaissance platoons, a VNSF team, and his own thirteen-man SFOD-A 101. Altogether the troops defending Lang Vei totaled about 480 men.

The camp was heavily equipped with crew served automatic and indirect fire weapons and had two 106mm recoilless rifles as well as one 57mm recoilless rifle for each of the four companies. One of the 106s was emplaced in the 2d Combat Reconnaissance Platoon’s sector to cover the southern avenue of approach into Lang Vei from Lang Troai Village. The other recoilless rifle was positioned in the 3d Recon Platoon’s sector providing flanking fires on any vehicle targets moving along Highway 9. Each 106mm recoilless rifle had over 20 HE rounds. Artillery support for the camp included sixteen 175mm guns, sixteen 55mm guns, and eighteen 105mm howitzers. Fire support was well planned – Willoughby registered a variety of concentrations, emphasizing likely avenues of approach and suspected enemy staging areas.

The buildup at Khe Sanh continued as part of GEN Westmoreland’s plan to stop the infiltration of NVA units down the Ho Chi Minh trail and draw large concentrations of GEN Vo Nguyen Giap’s NVA Divisions into a conventional set piece battle. Although many compared the deployment of forces at Khe Sanh with the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, Westmoreland was confident that superior American technology and firepower would defeat the NVA. The Special Forces camp at Lang Vei continued its intelligence collection mission with the intent of providing early warning of the widely hoped for NVA attack.

Giap was also building up his forces in preparation for the Tet Offensive and by January of 1968 several NVA divisions encircled the Marines at Khe Sanh, putting the nearby, and more westerly, camp at Lang Vei at risk. During this NVA buildup Lang Vei’s CIDG patrols encountered such heavy contact with elements of the NVA 324B Division that by December the indigenous troopers refused to patrol outside the camp’s perimeter.

Willoughby needed help. Schungel’s headquarters sent help in the form of the Mobile Strike Force or “Mike Force” from the C Detachment in Ban Me Thuot. The Mike Force “strikers” were well-armed indigenous troops (in this case 196 Hre Montagnards from Ban Me Thuot) led by experienced Special Forces troopers. The Mike Force was trained to operate in the midst of enemy held territory. Many were qualified paratroopers. The Mike Force, while successful in their previous missions, had suffered heavy casualties and the remaining combat-hardened veterans of the Mike Force (under the command of 1LT Paul Longgrear) were airlifted into Lang Vei on 22 December. They immediately began running patrols into Laos. The Mike Force recon patrols soon produced results.

In January, they found an empty tank park just a few kilometers across the river, which contained fresh impressions of tracked vehicles. According to one of the Special Forces NCOs leading the Mike Force the reports sent to Khe Sanh and Saigon were dismissed by the brass as exaggerated or false….”You guys are just trying to make yourself look good. The NVA haven’t got tanks!” On 24 January an Air Force FAC spotted five tanks along HWY 9 and called in an air strike destroying one vehicle.

That same day, Laotian troops of the 33rd Royal Laotian Battalion (sometimes referred to as the 33rd Laotian Volunteer Battalion) and their families appeared at Lang Vei. Their base at Ban Pho, just 12 kilometers from Lang Vei, was overrun two days earlier by elements of the 304th and 325th NVA Divisions. According to the Laotian commander the attack was led by tanks. Willoughby believed the Laotians fled at the very first sight of the enemy since their weapons were unfired and their column contained no wounded. With the arrival of the terrified Laotians the Special Forces troopers began to take the possibility of a tank attack very seriously and 100 LAWs (66mm Light Anti-tank Weapons)2 were immediately airlifted into the camp.

An NVA POW soon provided further confirmation of both the impending attack on Lang Vei and the presence of NVA armor in the vicinity. On 30 January 1968 NVA Private Luong Dinh Du wandered into Lang Vei. He walked right past the dozing Montagnard gate guards and into the team house, causing its somewhat disconcerted occupants to dive for cover. Private Luong was a rifleman from the 8/66 Regiment, 304th NVA Division. His unit had suffered heavy casualties in attacks against Marine positions around Khe Sanh, so he had deserted his regiment to ” Chieu Hoi,” surrender. Luong cooperatively answered the Special Forces interrogator’s questions. Yes, he said, his unit was preparing to assault Lang Vei. As part of a sapper team he participated in a reconnaissance of the camp two nights previous to his surrender. Luong said he hadn’t seen any tanks supporting his unit. He was turned over to Marine interrogators at Khe Sanh and after further questioning admitted he had heard the clanking of armored vehicle “tracks” which he thought were probably tanks.

Training on the newly arrived LAWs was limited to Willoughby’s team and ten of the CIDG troops. After a live fire practice there were only seventy-five LAWs left. Unfortunately the Special Forces soldiers discounted the actual possibility of an armor assault on Lang Vei. They expected the tanks, when and if they came, to function in a fire support role by firing their guns from the cover of the jungle.