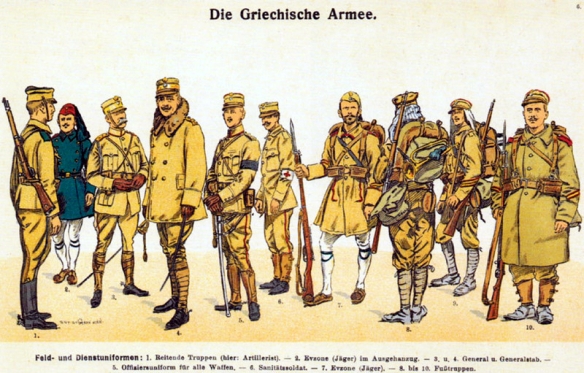

Field uniforms of the Greek Army during the Balkan Wars.

An Albanian kulla surrounded by Turkish cavallery (Photo: Ernst Jäckh, 1911).

During 1912–13 the Balkan Peninsula witnessed two wars: the First Balkan War, which saw an alliance of Balkan states all but destroy the Ottoman presence in the region, and the Second Balkan War, fought between the former allies over the division of the spoils. The Balkan Wars were the result of the incomplete processes of nation-state formation in southeastern Europe at the beginning of the 20th century. Ever since the Congress of Berlin in 1878 warranted the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire in the region, the dominant foreign policy goal of the Balkan states had been expanding into European provinces. Their main motive was to recover territories that were perceived to be under foreign occupation. Thus, one of the dominant claims of the Balkan states at the time was that their fellow ethnic kin were still oppressed by the Ottoman sultan. Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro justified their desire to extend into Ottoman-controlled Macedonia and Thrace through the principle of “liberation” of subjugated populations. For this purpose each country supported armed groups of its conationals that subverted and challenged the Ottoman regime. One of the aims of the Young Turk revolutions of 1908 had been precisely to end these revolts, suppress rival national identities, and “Ottomanize” the population.

In this context the situation in the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire impressed on the Balkan governments the need to cooperate. External great powers such as Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Italy were also sizing up the opportunity to get their share of the crumbling Ottoman state, which was referred to at the time as the “sick man of Europe.”

The war that Italy launched against the Ottoman Empire in September 1911 hastened the resolve of Balkan governments to sit at the negotiating table. On March 13, 1912, Bulgaria and Serbia signed a treaty of alliance and friendship, which was accompanied by a secret annex anticipating war with Turkey and providing for the division of territorial acquisitions in case of a successful war. According to this annex the territory of Macedonia was to be divided into three zones: two zones that would belong, respectively, to Bulgaria and Serbia and a third one that was contested and would be subject to the arbitration of the Soviet czar. At the same time Greece and Bulgaria were conducting separate negotiations, which culminated in the signing of a mutual defense treaty on May, 29, 1912, assuring support in case of war with Turkey. Bulgaria and Serbia had separate discussions with Montenegro, which concluded with verbal agreements that provided for mutual actions against the Ottoman state. By autumn the Balkan governments had managed to prevail over their mutual distrust and had formed a Balkan League premised on an extensive system of bilateral treaties.

The Balkan Wars began immediately afterward. On September 26, 1912, Montenegro opened hostilities invoking a long-standing frontier dispute as an excuse for declaring war. On October 2 Turkey hastily concluded a peace treaty with Italy, and on the next day it broke diplomatic relations with Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro but tried to mend relations with Greece. On October 4, 1913, the Ottoman Empire declared war on the Balkan League. In turn Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro declared war, accusing the Sublime Porte of not having implemented an article of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, which insisted on the recognition of the minority rights of their conationals in Macedonia. This event began the First Balkan War.

With specific manifestos the governments of Athens, Belgrade, and Sofia informed their citizens that they were to fight for a common cause and against Ottoman tyranny. Military operations began on all frontiers of European Turkey. Within a month after the start of hostilities, the Balkan armies had won spectacular victories on all fronts. The Bulgarian troops had pushed the Ottoman army to the Çatalca line of defense, just 40 kilometers outside of Istanbul, and had besieged Adrianople (modern-day Edirne in Turkey). The Serbs had surged into Macedonia, reaching Monastir (Bitolj) on November 17, 1912, and together with Montenegrin forces had occupied the Sandzak of Novi Pazar and had besieged the town of Scutari (today Shkodra in Albania). The Greek troops advanced in Thessaly. They entered Thessalonica on October 28, only a few hours before the arrival of a Bulgarian detachment, and the town was occupied by both armies. In Epirus Greek detachments advanced all the way to Janina (present-day Ioannina in Greece) and on November 10 laid siege to the city.

By December 1912 the Ottoman rule in the Balkans was over. Save for the besieged Adrianople, Scutari, and Janina, the Ottoman troops had been driven out of the former European provinces beyond the Çatalca line covering Istanbul. Alarmed by the success of the Balkan armies, the great powers imposed an armistice on the belligerents on December 3, 1912. It was signed by Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro, who pledged that their troops would remain in their positions. Greece, however, did not join in, as it wanted to continue the siege of Janina and carry on with the blockade of the Aegean coastline. Yet despite the continuation of hostilities in Epirus, Greece, together with Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Turkey, took part in the peace conference that opened in London on December 16, 1912. After two months of negotiations, toward the end of January 1913, a peace agreement seemed to be in sight. However, on January 23, 1913, a group of disgruntled Turkish officers overthrew the Ottoman government.