BY DENIS J. B. SHAW

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the great Russian soil scientist V. V. Dokuchaev and his followers began to describe the great soil belts which cross the East European plain in a west–east direction and which he ascribed not to geological variations but to the differential effects of climate, vegetation, hydrology, erosional processes and other factors acting over a lengthy period of time. Eventually Russian scientists defined the concept of ‘natural’ or ‘geographical’ zonation according to which not only soils but also climate, flora, fauna, hydrology, relief and other factors vary zonally and in an interdependent way, not in Russia only but also at a global scale. Russian territory, as defined for the late seventeenth century, can be divided into four major zones according to this approach; from north to south they are: tundra, forest (subdivided into boreal forest and mixed forest), forest-steppe and steppe.

The Eastern Slavs who moved on to the East European plain in the early centuries ad, and the Rus’ who moved down from the north-west, gradually intermingled with Finno-Ugrian, Baltic and other peoples who lived in the mixed forest zone of the central part of the plain. The mixed forest zone is a region of roughly triangular shape with its base to the west against the Baltic and the western frontier of the former Russian Empire (thus including the territory of present-day Belarus and north-west Ukraine), and its apex pointing towards the Urals in the east. The northern boundary runs approximately south-eastwards from St Petersburg and Novgorod towards Iaroslavl’ and Nizhnii Novgorod; the southern runs north-eastwards from Kiev towards Briansk, Kaluga, Riazan’ and so to Nizhnii Novgorod where the mixed forest practically disappears between the boreal forest to the north and the foreststeppe to the south. It then continues in a narrow strip eastwards to the Urals, but not beyond. According to one estimate the zone embraced about 12 per cent of the territory of European Russia at the end of the seventeenth century, and at the time of the first revision (census) in 1719 contained about 42.5 per cent of that territory’s registered population.

The mixed forest zone’s triangular shape reflects environmental conditions on the East European plain. The degree of continentality increases as one moves east away from the Baltic and Central Europe and the zone is gradually squeezed between the moisture-abundant regions of the boreal forest to the north and the moisture-deficit regions of the forest-steppe and steppe to the south. A west–east axis through the zone also defines a line of diminishing agricultural potential, with gradually reducing precipitation levels and longer and more severe winters as one moves towards the east. The zone formed the heartland for Russian agricultural settlement and activity throughout the period embraced by this book. As its name suggests, the mixed forest is a transitional region containing both coniferous forests, which predominate towards the north, and deciduous woodlands, which become more common as one moves south. Common conifers include fir, spruce and pine on sandy soils while oak, elm, birch, lime, ash, maple and hornbeam are deciduous varieties. The predominant soils are turfy podzols, which are usually rather acidic, and the relatively fertile grey forest soils, which become more common towards the south.

For many centuries the mixed forest zone, despite its indifferent soils and rather severe continental climate, thus formed the agricultural heartland of the Russian realm. Within the region conditions for settlement and agriculture varied greatly, however. To the north-west, in the region of the Valdai Hills and in areas further west and north, is a landscape greatly affected by recent glacial and fluvio-glacial deposition in which morainic deposits have interfered with the natural drainage and the many lakes, boulders, marshes and morainic features formed a serious barrier to agricultural settlement. Only in some more favoured regions like the area stretching south-west from Lake Il’men’ with loamy soils did cultivation prove possible. Soils are generally podzolised. Further south lies the uneven region of terminal moraines known as the Moscow–Smolensk upland, providing better drainage and better prospects for peasant settlement, whilst south again, fringed by the southwestern spurs of the central Russian upland, is the Dnieper lowland. Although rather poorly drained historically, this area, with its turfy podzols and grey forest soils developed on loess, and with pine together with broadleaved forests of beech, hornbeam and oak, provided numerous opportunities for peasant farmers.

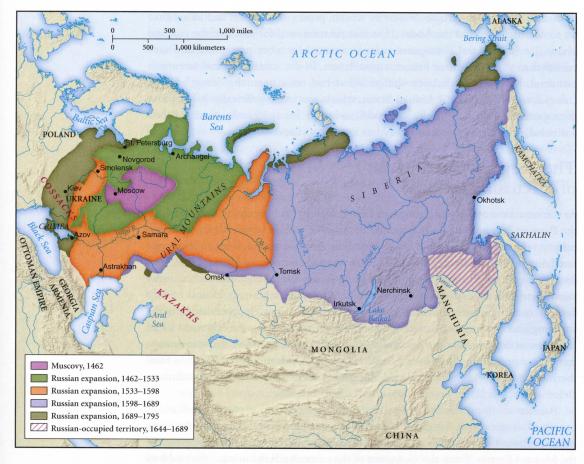

North-east of the Dnieper lowland, on the interfluve between the Volga and the Oka (the district forming the heartland of the Muscovite state), agricultural settlement was greatly influenced by a detailed topography which reflected the effects of underlying geology, glacial deposition and fluvial action. This was and is a complex landscape of forest, marsh, meadow, pasture and glade which is difficult to summarise and whose patterns of soil and vegetation vary in accordance with local relief, drainage and other factors. Forest cover increases towards the east and north, and, especially beyond the Volga to the north, glacial deposits restricted drainage and acted as hindrances to settlement. To the south, and particularly beyond the Oka, drainage improves and soil fertility increases, and this region fringing on the forest-steppe eventually proved very favourable for agriculture. On the interfluve itself the well-favoured districts where fertile forest-steppe-like soils lie like islands within the mixed forest (like the famous Vladimir Opol’e) contrast with the sandy, ill-drained Meshchera Lowland south-east of Moscow, a mixed territory of pine and spruce forests and marsh. Finally, beyond the Volga to the east and stretching away towards the Urals, natural conditions were affected by the greater continentality and it was only towards the end of our period that the mixed forest began to be subject to agricultural colonisation.

The mixed forest environment provided peasants with a variety of resources for their subsistence. It may be that initial settlement followed valleys where there was easy access to rivers and streams for water and transport, to meadowlands and to woodland. The better-drained places, such as river terraces, were favoured. Broadleaved tree species were usually not difficult to clear for cultivation. Later, as technology improved and it became feasible to dig deeper wells, watersheds could be settled also. Scholars have discussed how relatively simple agricultural landscapes (like cultivation in patches in the forest perhaps using temporary slash-and-burn techniques) gradually evolved into permanent landscapes with more intensive forms of agriculture, albeit with temporary patches still frequently scattered through the forest. Rye, barley and oats were the principal food crops grown. The hayfields, which might include water meadows, pastures and once again even remote glades in the forest, provided feed for the peasants’ limited livestock. Livestock farming involved the necessity of stall-feeding during the long winter months. Woodland provided the peasants with many necessities: timber (for building), wood (logs, poles, rods, brushwood, bark for many purposes including fences, implements, utensils, furniture, fuel, making potash, resin, tar, pitch), food (berries, nuts, fruit, fungi, game, honey) and additional pasturing for animals. Rivers provided fish. Like all pre-industrial societies, traditional Russia made use of a wide variety of plant and animal products for textiles, clothing, foods, flavourings, medicines, tanning, dyeing, preserving, building and other purposes.