Important World War II Allied resupply effort.

The fall of France emboldened Italian dictator Benito Mussolini to declare war on Britain and thereby open the Mediterranean Sea as a new theater of operations. The entry of Italy into the war was a severe strategic threat. Its geographic position endangered Britain’s Mediterranean commerce lanes, whereby oil and supplies from the eastern empire passed through the Suez Canal to the home islands. At least on paper, the Italian fleet was an imposing force. It comprised 6 battleships, 20 cruisers and 59 destroyers of various types, and 122 submarines. The Mediterranean campaign quickly centered on Britain’s attempts to keep its trade lanes open and defend the island base of Malta, which lay astride the Mediterranean’s trade routes.

Italian naval strength, however, proved illusory. While Italy had some fine ships, they lacked radar, night-fighting equipment, antisubmarine warfare capabilities, a doctrine for joint operations between naval and air forces, and adequate antiaircraft defense. The latter deficiency was soundly exposed in the November 1940 raid on Taranto where British air attacks sank three battleships, damaged a fourth, and crippled a cruiser and destroyer. By spring 1941, British sea and land-based air attacks had reduced the Italian navy to one operational battleship and a few cruisers, thus removing the Italian fleet as a serious threat to Britain’s naval effort.

During World War II, Malta was a threat to German and Italian efforts to supply their forces in North Africa. To reach North Africa, Axis ships had to pass close to the British-controlled island, the “unsinkable aircraft carrier” less than 100 miles from Sicily. Malta’s value as an offensive base was debatable, but its worth as a symbol was immeasurable. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill insisted that it be maintained regardless of the cost, and a number of convoys ran the gauntlet of Axis air and naval power.

Although the Italians had bombed Malta early in the war, the introduction of the Luftwaffe in February and March 1941 gave the Axis control over the central Mediterranean. For part of 1941 and most of 1942 supplies had to be fought through to Malta. Of six convoys sent to Malta from both ends of the Mediterranean, only parts of four reached the island. In addition to these convoys aircraft carriers ferried some 350 aircraft to Malta. Several submarines and small fast ships made runs to the island, but these were of very limited use, given the island’s needs.

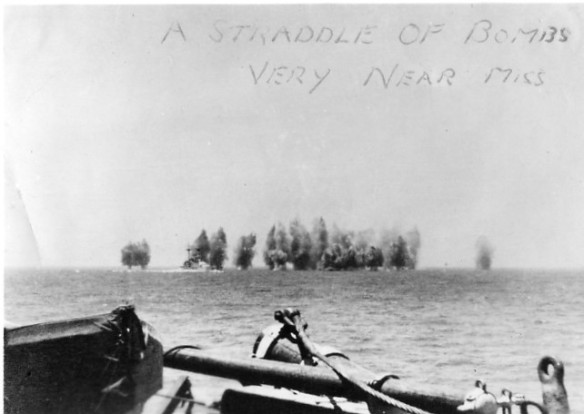

In June 1942 the British attempted to resupply Malta with a convoy from Gibraltar and one from Alexandria (Operations harpoon and vigorous), in an attempt to overwhelm Axis forces by stretching their resources. The Alexandria convoy turned back after heavy fighting, and this left the Gibraltar convoy alone against Italian light naval units, submarines, and aircraft from Sicily. Four of the six merchantmen were sunk, but the two remaining reached Malta. The escorting force lost one cruiser, and five destroyers and three cruisers were heavily damaged. Allied air operations sank one Italian cruiser and damaged battleship Littorio.

The most costly convoy operation in support of Malta was Operation pedestal. It took place during 10–15 August 1942 and involved 4 British aircraft carriers—Eagle, Victorious, Furious, and Indomitable—along with 2 battleships, 7 cruisers, and 27 destroyers. The Italian navy did not challenge the convoy, but Axis air, motor torpedo boat (MTB), and U-boat attacks inflicted heavy losses. Nine merchantmen, the carrier Eagle, 2 cruisers, and a destroyer were sunk; carriers Victorious and Indomitable and 2 cruisers were damaged. Of the five merchantmen that reached Malta, four were damaged. One of the damaged ships was the tanker Ohio, which delivered a precious cargo of aviation fuel and oil to the Malta strike force.

The 8 November 1942 Allied landings in North Africa and the invasion of Italy made Malta a backwater. Malta’s chief role was as a symbol, although operations from there against Axis shipping lines materially aided the Allied victory in North Africa. Whether this was worth the cost of supplying and defending the island is still debated.

References

MacIntyre, Donald. The Battle for the Mediterranean. London: Batsford, 1964.

Roskill, Stephen W. White Ensign: The British Navy at War, 1939–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1960.