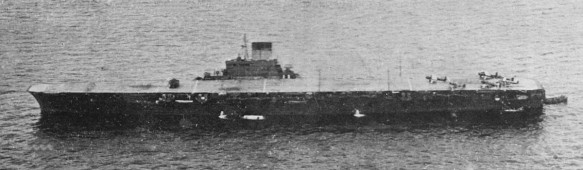

TAIHŌ was completed on 7 March 1944. Following several weeks of service trials in Japan’s Inland Sea, she was deployed to Singapore, arriving there on 5 April. TAIHŌ was then moved to Lingga Roads, a naval anchorage off Sumatra, where she joined Shokaku and Zuikaku of the First Carrier Division, First Mobile Force. All three carriers engaged in working up new air groups by practicing launch and recovery operations and acting as targets for mock aerial attacks staged from Singapore airfields by their own planes. On 15 April, Vice-Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa officially transferred his flag from Shokaku to TAIHŌ. Shortly thereafter, the First Mobile Force departed Lingga and arrived on May 14 at Tawi-Tawi off Borneo where the fleet could directly refuel with unrefined Tarakan crude oil and await execution of the planned “decisive battle” known as Operation A-GO.

When American carrier strikes against the Marianas indicated an invasion there was imminent, the Japanese Combined Fleet staff initiated Operation A-GO on June 11. TAIHŌ and the rest of Ozawa’s First Mobile Force departed Tawi-Tawi on June 13, threading their way through the Philippine Islands and setting course for Saipan to attack American carrier forces operating in the vicinity.

On 19 June 1944, TAIHŌ was one of nine Japanese aircraft carriers involved in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. At 0745 that morning, she was turned into the wind to launch her contribution (16 Zero fighters, 17 Judy dive-bombers and 9 Jill torpedo-bombers) to Ozawa’s second attack wave. As TAIHŌ’s planes circled overhead to form up, the American submarine USS Albacore (SS-218) fired a spread of six torpedoes at the carrier. One of Taihō’s strike pilots, Warrant Officer Sakio Komatsu, saw the torpedo wakes, broke formation and deliberately dove his plane into the path of one torpedo; the weapon detonated short of its target and four of the remaining five missed. The sixth torpedo, however, found its mark and the resulting explosion holed the carrier’s hull on the starboard side, just ahead of the island. The impact also fractured the aviation fuel tanks and jammed the forward elevator between the flight deck and upper hangar deck.

With the ship down 5 feet (1.5 m) by the bows due to flooding, the forward elevator pit filled with a mixture of seawater, fuel oil and aviation gasoline. TAIHŌ’s captain marginally reduced her speed by a knot and a half to slow the ingress of seawater into the hull where the torpedo had struck. As no fires had started, Vice-Admiral Ozawa ordered that the open elevator well be planked over by a flight deck damage control party in order to allow resumption of normal flight operations. By 0920, using wooden benches and tables from the petty officers’ and sailors’ mess rooms, this task was completed.[24] Ozawa proceeded to launch two more waves of aircraft.

Meantime, leaking aviation gasoline accumulating in the forward elevator pit began vaporising and soon permeated the upper and lower hangar decks. The danger this posed to the ship was readily apparent to the damage control crews but, whether through inadequate training, lack of practice (only three months had passed since the ship’s commissioning) or general incompetence, their response to it proved fatally ineffectual. Efforts to pump out the damaged elevator well were bungled and no one thought to try and cover the increasingly lethal mixture with foam from the hangar’s fire suppression system.

Because TAIHŌ’s hangars were completely enclosed, mechanical ventilation was the only means of exhausting fouled air and replacing it with fresh. Ventilation duct gates were opened on either side of hangar sections #1 and #2 and, for a time, the carrier’s aft elevator was lowered to try and increase the draught. But even this failed to have any appreciable effect and, in any case, air operations were resumed about noon, requiring the elevator to be periodically raised as aircraft were brought up to the flight deck. In desperation, damage control parties used hammers to smash out the glass in the ship’s portholes.

TAIHŌ’s chief damage control officer eventually ordered the ship’s general ventilation system switched to full capacity and, where possible, all doors and hatches opened to try and rid the ship of fumes. This resulted in saturation of areas previously unexposed to the vapors and increased the chances of accidental or spontaneous ignition exponentially. Taihō became a floating time bomb.

About 1430 that afternoon, six and a half hours after the initial torpedo hit, Taihō was jolted by a severe explosion. A senior staff officer on the bridge saw the flight deck heave up. The sides blew out. Taihō dropped out of formation and began to settle in the water, clearly doomed. Though Admiral Ozawa wanted to go down with the ship, his staff prevailed on him to survive and to shift his quarters to the cruiser Haguro. Taking the Emperor’s portrait, Ozawa transferred to Haguro by destroyer. After he left, Taihō was torn by a second thunderous explosion and sank stern first at 1628, carrying down 1,650 officers and men out of a complement of 2,150.