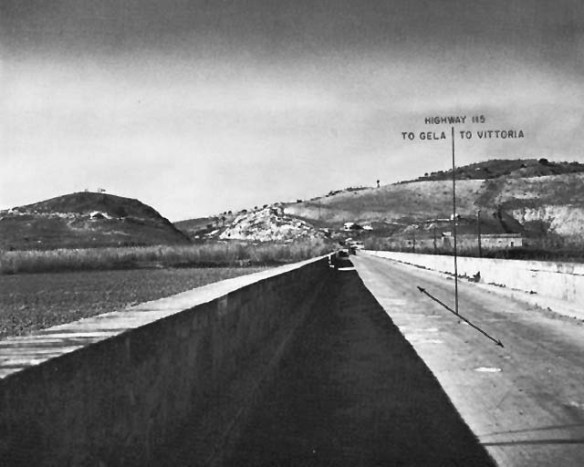

THE PONTE DIRILLO CROSSING SITE, seized by paratroopers on D-day.

At various airfields in North Africa during the afternoon of 9 July, British and American airborne troops, under a glaring sun, made the final preparations for the operation scheduled to initiate the invasion of Sicily.1 While crews ran checks on the transport aircraft, the soldiers loaded gliders, rolled and placed equipment bundles in para-racks, made last-minute inspections, and received final briefings. Heavily laden with individual equipment and arms, with white bands pinned to their sleeves for identification, the troops clambered into the planes and gliders that would take them to Sicily.

The British airborne operation got under way first as 109 American C-4 is and 35 British Albermarles of the U.S. 51st Troop Carrier Wing at 1842 began rising into the evening skies, towing 144 Waco and Horsa gliders. Two hours later, 222 C-4is of the U.S. 52d Troop Carrier Wing filled with American paratroopers of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team and the attached 3d Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry, were airborne.

The British contingent made rendezvous over the Kuriate Islands and headed for Malta, the force already diminished by seven planes and gliders that had failed to clear the North African coast. Though the sun was setting as the planes neared Malta, the signal beacon on the island was plainly visible to all but a few aircraft at the end of the column. The gale that was shaking up the seaborne troops began to affect the air columns. In the face of high winds, formations loosened as pilots fought to keep on course. Some squadrons were blown well to the east of the prescribed route, others in the rear overran forward squadrons. Despite the troubles, 90 percent of the air craft made landfall at Cape Passero, the check point at the south-eastern tip of Sicily, though formations by then were badly mixed. Two pilots who had lost their way over the sea had turned back to North Africa. Two others returned after sighting Sicily because they could not orient themselves to the ground. A fifth plane had accidentally released its glider over the water; a sixth glider had broken loose from its aircraft–both gliders dropped into the sea.

The lead aircraft turned north, then northeast from Cape Passero, seeking the glider release point off the east coast of Sicily south of Syracuse. The designated zigzag course threw more pilots off course, and confusion set in. Some pilots released their gliders prematurely, others headed back to North Africa. Exactly how many gliders were turned loose in the proper area is impossible to say perhaps about 115 carrying more than 1,200 men. Of these, only 54 gliders landed in Sicily, 12 on or near the correct landing zones. The others dropped into the sea. The result: a small band of less than 100 British airborne troops was making its way toward the objective, the Ponte Grande south of Syracuse, about the time the British Eighth Army was making its amphibious landings.

As for the Americans who had departed North Africa as the sun was setting, the pilots found that the quarter moon gave little light. Dim night formation lights, salt spray from the tossing sea hitting the windshields, high winds estimated at thirty miles an hour, and, more important, insufficient practice in night flying in the unfamiliar V of V’s pattern, broke up the aerial columns. Groups began to loosen, and planes began to straggle. Those in the rear found it particularly 117 difficult to remain on course. Losing direction, missing check points, the pilots approached Sicily from all points of the compass. Several planes had a few tense moments as they passed over the naval convoys then nearing the coast-but the naval gunners held their fire. Because they were lost, two pilots returned to North Africa with their human cargoes. A third crashed into the sea.

Even those few pilots who had followed the planned route could not yet congratulate themselves, for haze, dust, and fires all caused by the pre-invasion air attacks obscured the final check points, the mouth of the Acate River and the Biviere Pond. What formations remained broke apart. Antiaircraft fire from Gela, Ponte Olivo, and Niscemi added to the difficulties of orientation. The greatest problem was getting the paratroopers to ground, not so much on correct drop zones as to get them out of the doors over ground of any sort. The result: the 3,400 paratroopers who jumped found themselves scattered all over south-eastern Sicily-33 sticks landing in the Eighth Army area; 53 in the 1st Division zone around Gela; 127 inland from the 45th Division beaches between Vittoria and Caltagirone. Only the 2d Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry (Maj. Mark Alexander), hit ground relatively intact; and even this unit was twenty-five miles from its designated drop zone.

Except for eight planes of the second serial which put most of Company I, 505th Parachute Infantry, on the correct drop zone just south of the road junction objective; except for eighty-five men of Company G of the 505th who landed about three miles away; and except for the headquarters and two platoons of Company A and part of the 1St Battalion command group, which landed near their scheduled drop zones just north of the road junction, the airborne force was dispersed to the four winds.

The planes carrying the headquarters serial, which included Colonel Gavin, the airborne troop commander, were far off course, having missed the check point at Linosa, the check point at Malta, and even the southeaster coast of Sicily. The lead pilot eventually made landfall on the east coast near Syracuse, oriented himself, and turned across the southeast corner of the island to get back on course. Assuming that the turn signaled the correct drop zone, the pilots of the last three planes- carrying the demolition section designated to take care of the Ponte Dirillo over the Acate River southeast of Gela-released their paratroopers. The other pilots, about twelve of them, dropped their loads in a widely dispersed pattern due south of Vittoria about three miles inland on the 45th Division’s right flank.

Coming to earth in one of these sticks, Gavin found himself in a strange land. He was not even sure he was in Sicily. He heard firing apparently everywhere, but none of it very close. Within a few minutes he gathered together about fifteen men. They captured an Italian soldier who was alone, but they could get no information from him. Gavin then led his small group north toward the sound of fire he believed caused by paratroopers fighting for possession of the road junction objective.

The fire actually marked an attack by about forty paratroopers under 1st Lt. H. H. Swingler, the 505th’s headquarters company commander, who was leading an attack to overcome a pillbox-defended crossroads along the highway leading south from Vittoria. Other sounds of battle came from Alexander’s 2d Battalion, which was reducing Italian coastal positions near Santa Croce Camerina. Near Vittoria, scattered units of the 3d Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, had coalesced and were also engaged in combat. The eighty-five men from Company G, under Capt. James McGinity, had seized Ponte Dirillo. Elsewhere, bands of paratroopers were roaming through the rear areas of the coastal defense units, cutting enemy communications lines, ambushing small parties, and creating confusion among enemy commanders as to exactly where the main airborne landing had taken place.

But less than 200 men were on the important high ground of Piano Lupo, near the important road junction, hardly the strength anticipated by those who had planned and prepared and were now executing the invasion of Sicily.