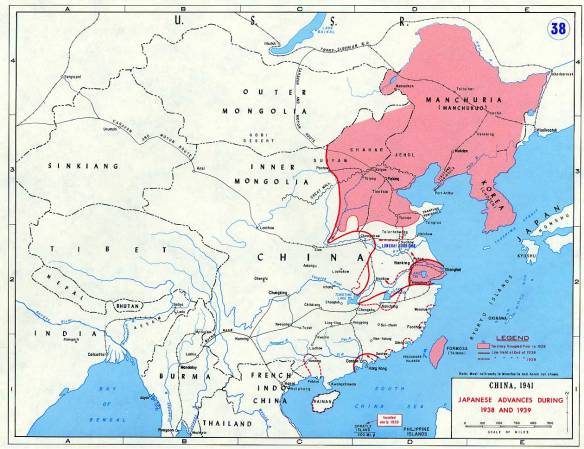

The Japanese invasion, 1937–45 (Japanese/GMD/CCP territory)

The Japanese Army first moved southward in the summer of 1937 (dates of conquests given “year-month”), and then, supported by the Navy, up through the rich agricultural lands along the Yangzi River into central China. The Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek were pushed into the backward southwest, while the main CCP was maintained in the far northwest. Yet the Japanese occupation was never secure.

Japan had put 700,000 troops into China by the end of 1937, a number that was to rise to 1 million and finally 1.5 million. By way of contrast, the Chinese Nationalist army had about 1.7 million soldiers, but only 80,000 were fully equipped with modern weapons. About 300,000 had received some German-style training. Worse, Chinese forces remained divided among semi-independent and jealous commanders. At the beginning of the year the Japanese consolidated their control over the railroads, most of the north China plain, and major rivers. The navy sailed up the Yangzi to Wuhan and in 1940 to Yichang, chasing the Nationalist government far into the interior. Chiang Kai-shek was forced to relocate his capital to Chongqing, while Japan controlled the coastal regions.

Virtually all major cities were in Japanese hands by the end of 1938. Yet still the Chinese did not surrender. Japan’s military strategy was to seize the cities and key lines of communication and transportation. From this network of points and lines, control would expand into the countryside, through Chinese agents. Most of the active collaborators were local elites or sometimes bandit gangs. Yet Chinese resistance continued. When the Japanese spread their network thin, guerrillas attacked weak points, such as railroad lines, and then escaped among the peasantry before reinforcements could be brought to bear. Local collaborators proved ineffective or even secretly anti-Japanese while genuine collaborators were subject to assassination by partisans.

In 1940, following a major but failed offensive by CCP troops in northern China, Japan began sweeps of entire districts known to shelter guerrillas. This was the “three alls” policy: kill all, burn all, destroy all. In northern China entire villages were razed, crops seized or destroyed, and peasants slaughtered. The strategy succeeded in reducing an underground Communist structure to roving guerrillas and reduced the size of the Communist base areas, but it obviously was no way to make China an economically productive part of the Japanese Empire. Even if Japan could afford the loss of soldiers in battle, the financial costs were another question. The bill for the China war soon came to $5 million per day. Japan, a creditor nation after World War I, took on a large national debt. As the war with China stretched on with no end in sight – only further troop commitments – total mobilization at home followed. Rationing was imposed as early as 1938, and under “total war” conditions Japan’s domestic politics became increasingly dictatorial.

Japan needed oil, rubber, and other raw materials, which made it dependent on the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands. If Japan could take the Western colonies in Southeast Asia, it would satisfy its immediate material needs. But war with either the United States or the Soviet Union was highly risky. The Soviet Union had put into Mongolia and Siberia twice the military power Japan had in Manchuria. If the main enemy was Russia, then war with China, much less the Western powers, was unwise. Conversely, would the United States stand by if the war were extended to Southeast Asia? The industrial capacity of the United States dwarfed Japan’s, and as the China war dragged on, US reaction grew increasingly stern: in 1938 it banned the export of aeronautical materials in a “moral embargo” and in 1939 abrogated the US–Japanese trade treaty. When Japan took Indochina in July 1941, it faced a US–Dutch–British export ban on the life-blood of military operations: oil and iron ore. For Japan, paranoia about the “ABCD” encirclement was coming true. The American embargoes, with British, Chinese, and Dutch support, were going to make the China war impossible to continue.

But if China could be knocked out quickly – as some in the Japanese military still thought possible – and if it could be economically incorporated into the Japanese empire along with Korea and Manchuria, then Japan would be in a very strong position. All of this was occurring in the context of European instability. The alliance between Germany and Japan, formalized in the Anti-Comintern Pact of November 1937, was a realpolitik decision made in spite of Nazi Germany’s official racism, which included “Asiatics” among the inferior races, and Japan’s official condemnation of Western imperialism. From Japan’s point of view, the treaty was simply designed to provide it with assistance in case of war with the Soviet Union. It was thus effectively broken by the Nazi–Soviet pact of 1939, which shocked the entire world and led to great confusion in Tokyo. None the less, Japan’s military leaders – facing imminent shortages of vital supplies and the enormous expenses of the ongoing China campaign – decided on double or nothing.