Although the rise of fighter aircraft was a product of the war itself— the need to attack enemy reconnaissance aircraft and protect one’s own—the idea of using aircraft and airships for bombing the enemy had been sown in the public’s imagination by journalists and novelists prior to the war. Novelists like H. G. Wells reflected the belief that aerial bombardment would destroy both the enemy’s capacity to fight and will to fight. Although the reality of aerial bombardment during the First World War did not live up to the prewar hype, it was not because of a lack of effort. Even before the war, air power enthusiasts, like E. Joynson Hicks, a British M.P., had conceived of strategic missions for the bomber: attacks against an enemy’s military plants and transportation infrastructure; attacks against an enemy’s command and control centers; and attacks against the civilian population. By 1913 the French, Germans, British, and Italians were conducting bombing exercises and experimenting with bombsights and bomb release equipment. The advent of trench warfare gave new impetus to these ideas, as aircraft would be used tactically on the battlefield to bomb targets beyond the range of artillery and as both sides turned to strategic bombing and (in the case of the German zeppelin raids on Great Britain) terror bombing to weaken the enemy.

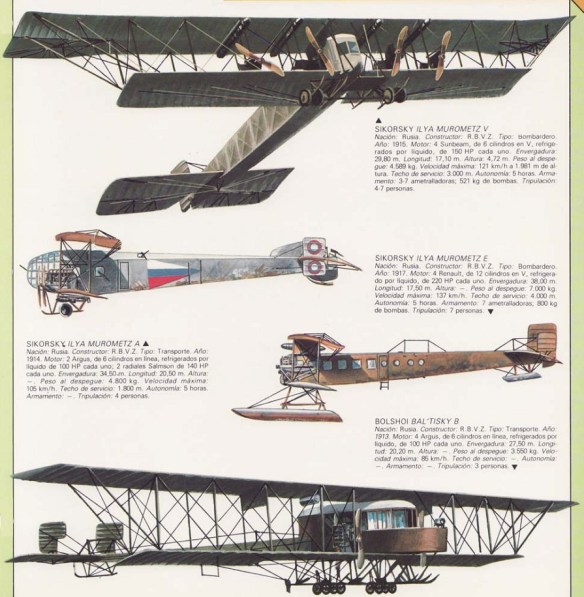

Most prewar aspirations for bombers centered upon airships, because they were capable of greater range and heavier bomb loads. When the Germans and French attempted to use their airships in the opening stages of the war, they soon discovered how vulnerable airships were to ground fire, as the Germans lost three zeppelins in 1 month’s time to enemy ground fire and the French had two of their airships damaged by their own infantry fire. As a result, both the French and Germans grounded their airships until 1915 and turned to the airplane. The Russian Igor Sikorsky and the Italian Giovanni Caproni ironically were far ahead of the aircraft designers among the other European powers. By the time war broke out in 1914 Sikorsky’s four-engine Ilya Muromet had successfully completed a 1,600-mile round-trip flight between St. Petersburg and Kiev. Meanwhile, Caproni was putting the finishing touches on a three-engine bomber that was ready to fly by October 1914. Lacking anything similar to what the Russians and Italians possessed, the French, British, and Germans were forced to rely upon reconnaissance aircraft until they developed bombers of their own. Indeed, by November commanding generals had authorized that all reconnaissance aircraft be equipped to carry bombs. At the time the government munition plants had not yet developed aerial bombs, so airmen generally improvised by adding tail fins to surplus artillery shells and converting them into bombs, at first dropped over the side by the observer and later fitted to bomb racks and released by either the pilot or observer.

Although Article 25 of the 1907 Hague Convention had outlawed the bombardment of nonmilitary targets, the inaccuracy of aerial bombardment made it impossible not to violate this provision. On the night of 26 August, for example, German zeppelins, operating out of Düsseldorf, began a series of bombing raids on Antwerp, Belgium. In the first raid, the Germans dropped 1,800 lbs of shrapnel bombs, partially destroying a hospital and killing twelve civilians. On 8 October the British launched a retaliatory raid with two Sopwith Tabloids, each carrying two 20-lb bombs. Although one of the planes succeeded in destroying Z-9 in its Düsseldorf shed, the other dropped its bombs on the Cologne railway station, killing three civilians. A similar, far more daring raid was carried out by four Avro 504 biplanes, each carrying four 20-lb bombs, against the zeppelin works at Friedrichshafen. Although only three of the planes reached their destination, they struck the hydrogen works and inflicted minor damage to the sheds. Although several German soldiers and workers were killed or wounded, neither of the two zeppelins were damaged and the gasworks was operational within a week.

Although these initial raids had been somewhat ad hoc affairs in which pilots of reconnaissance aircraft were given little to no instructions, the military high commands began issuing directives as to tactics by early 1915, such as releasing bombs at low altitude in order to improve accuracy, and specifying missions. Most bombing missions centered on enemy positions that were out of artillery range, but other targets included industrial centers far behind the lines. The French, for example, attempted to sever the rail lines in the Briey basin in Lorraine in hopes of disrupting Germany’s supply of iron ore. In addition, both sides conducted raids against enemy cities, often justifying them as retaliatory raids. The Germans, having occupied north-eastern France, were better placed to defend attacks against German cities because they were too far out of range from enemy bases to carry out attacks against Britain, France, and Russia. Although Italy was well equipped to carry out bombing raids on Austrian territory, its leaders were reluctant to do so because the targets lay in the heavily Italian populated areas that Italy hoped to annex.

Before the end of 1914 powers also began to organize units specifically intended to carrying out bombing missions. The French had formed Groupe de Bombardement No. 1 (G.B. 1) from three escadrilles composed of the new Voisin pusher aircraft, and the Germans had established the Brieftauben-Abteilung Ostende (B.A.O.) or “Ostend Carrier Pigeon Flight” for duty along the English Channel. In December 1914 aircraft from the B.A.O. carried out bombing attacks on Channel ports, whereas G.B. 1 bombers attacked the Badische Analin und Soda Fabrik the following spring after receiving reports that it had produced the deadly chlorine gas used at Second Ypres. Field Marshall Joffre even issued orders for an attack against Thielt after receiving intelligence reports that Kaiser Wilhelm II was scheduled for a visit on 1 November 1914. Although a change in the Kaiser’s schedule resulted in canceling the attack, it is significant to note that it would have been impossible to contemplate such a move a decade earlier. Similar attempts were made by the Germans against Nicholas II and by the French against Crown Prince Wilhelm and Bavarian Crown Prince Rupprecht.

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle, launched with a preliminary bombardment on 10 March 1915, marked the beginning of a new phase in the use of air power. Whereas aerial reconnaissance had provided British First Army Commander General Sir Douglas Haig with detailed information about the German defenses and led him to designate the salient around Neuve Chapelle as the target for his first assault, tactical bombing was attempted for the first time as part of a battle plan. Where bombs had previously been dropped sporadically by reconnaissance pilots, military commanders ordered strikes against a reported divisional headquarters in Fournes; the key railway stations at Menin, Douai, Lille, and Don; and the railway junction at Courtai. Flying a B.E.2 c, Captain Louis Strange dropped three 20-lb bombs on a stationary troop train at Courtai, reportedly killing or wounding seventy-five soldiers and disrupting traffic for 3 days. On the other hand, Captain Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt mistakenly dropped a 100-lb bomb on the railway station at Wavrin, thinking he was over Don. Because pilots lacked an effective bombing sight, they had to fly extremely low over their targets, which exposed them to enemy ground fire. When Strange returned from his bombing raid on Courtai, his plane was found to have at least forty bullet holes. Lieutenant William Rhodes-Moorhouse was not as fortunate. While dropping a 100-lb bomb at an altitude of 100 ft over Courtai, he was mortally wounded; an action for which he received the RFC’s first Victoria Cross.