Prittwitz was just about ready to order the final phase of the withdrawal when the Russian communication problems changed the picture dramatically. German I Corps intelligence officers had picked up a local message from Rennenkampf to his division commanders that had been broadcast, en clair (meaning without the use of codes), over radio waves. The message ordered a halt in movement on 20 August just south of the border town of Gumbinnen to give his men a rest and to allow supplies to be brought forward. The order went to I Corps commander, General Hermann von François, an aggressive officer with more than the usual German hatred of Slavs. He was already aghast at Prittwitz’s proposal to withdraw and voluntarily cede parts of Germany to the Russian invaders and had subsequently disobeyed his orders and moved his units east, not west. François informed Prittwitz that he was going to attack the Russians at Gumbinnen instead of falling back. Prittwitz had his doubts, but gave his impatient subordinate permission to proceed.

To make sure that the attack had every chance of success, Prittwitz ordered two of his corps to join François at Gumbinnen, leaving his fourth corps in reserve. François recklessly pressed ahead without waiting for the other two corps to complete their preparations. He attacked the much larger Russian forces at 4am on 20 August, achieving surprise and pushing Russian forces back as far as eight kilometres (6ve miles). François thought that he had scored a major victory and urged the other two German corps to come forward and complete the annihilation of the Russian First Army.

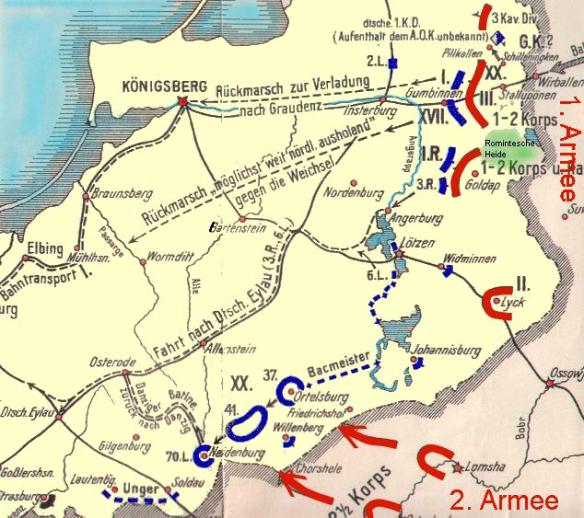

The two corps arrived on the battlefield piecemeal, with one arriving at 8am and the other only arriving at midday. François had in fact only fought against a weak advance guard; as the Germans forced their way east they came up against the main body of First Army, including its artillery. The three German corps fought separately against powerful (if inefficiently employed) Russian forces. Seeing how badly they were outnumbered and outgunned, the German XVII Corps began a withdrawal at the end of the day. The other two corps, including François’s I Corps, had little choice but to follow suit, leaving more than 6000 German prisoners in Russian hands.

Prittwitz panicked. His units were in disarray and he expected Rennenkampf to pursue with the utmost vigour. He also had no clear idea of where Samsonov’s Second Army was. He therefore feared that he might encircled and destroyed by much larger Russian forces. He designed an even more ambitious retreat, proposing to retire behind the Vistula River to buy time, even if such a withdrawal essentially meant abandoning all of East Prussia to the Russians. Prittwitz informed Moltke of his new plan, but his commander’s reaction was not what he had expected. Directing the attack on Paris from his headquarters in Luxembourg, Moltke went into a rage and ordered the withdrawal stopped immediately. He also informed Prittwitz that he and his chief of staff were being removed from command, leading to Prittwitz’s retirement. The defence of East Prussia would fall to the hands of new commanders with new ideas.