Sedan, already notorious as the site of a German victory in 1870, was a small city of about 12,000 inhabitants, lying mostly on the Ardennes side of the Meuse. It had been decided in advance to abandon the city and destroy the bridges if an attack occurred. The French would defend the other side of the Meuse, exploiting the natural obstacles offered by the river and the high ground of the left bank. From the forested hill of La Marfée, the French defenders had a superb view over the Germans on the other side. Thus, Huntziger considered Sedan to be the least vulnerable sector of his line. His main worry was that the Germans might attack further to the south-east in the vicinity of Mouzon with a view to taking the Maginot Line from the rear. To counter this eventuality Huntziger had stationed his best units on his right flank. The 17 km of the Sedan sector, on his left flank, was defended by the B-Series reservists of the 55DI. Quite apart from their deficiencies as soldiers, they were extremely short of anti-aircraft weapons—there was only one anti-aircraft battery in the whole area—and when the German planes attacked many men had only machine-guns and rifles to use against them.

On the night of 12–13 May, French artillery was effective in hampering German movements to the north of the Meuse where the steady arrival of German troops and armour provided an easy target. Then at 7 a.m. on the morning of 13 May, German planes started to attack the French positions. The Kleist group had about 1,000 planes at its disposal, mostly around Sedan. This was a massive concentration of airpower for such a narrow sector of the front. For the next eight hours, wave upon wave of German Stuka bombers pounded the French in what was one of the heaviest air assaults so far in military history. Although these attacks did little damage to French bunkers and gun positions, they had a devastating effect on morale.

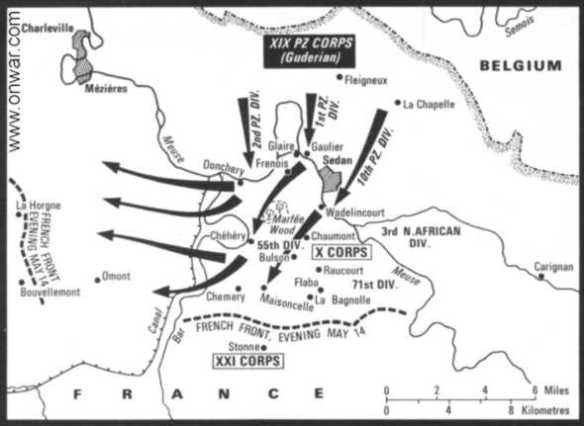

At about 3 p.m., after this prolonged bombardment, the Germans started their attempt to cross the Meuse. Guderian planned to use his three divisions for a three-pronged attack. The 10th Panzer Division was to cross on the left, and, once across the river, to secure the high ground of the Marfée heights above the village of Wadelincourt. The crossing was difficult. To reach the edge of the river and launch their rubber dinghies, the German troops had to wade through waterlogged meadows, all the time offering a prime target to the French troops defending the Marfée heights. Most of the boats were shot to pieces before they could even be thrown into the river. If the Germans did succeed in obtaining a foothold on the other bank, this success was due above all to the initiative of a few individuals. Among these was Staff Sergeant Rubarth and his squad of assault engineers. Having managed to cross the river, their dinghy only precariously afloat because of the weight of equipment it was carrying, they were able to rush the French bunkers with surprising ease. As Rubarth himself described the events later:

In a violent Stuka attack, the enemy’s defensive line is bombarded. With the dropping of the last bomb at 1500 hours, we move forward and attack with the infantry. We immediately sustain strong machine gun fire. There are casualties. With my section I reach the bank of the Meuse in a rush through a woodline. . . . Enemy machine guns fire from the right flank across the Meuse. . . . The rubber boat moves across the water. . . . During the crossing, constant firing from our machine guns batters the enemy, and thus not one casualty occurs. I land with my rubber boat near a strong, small bunker, and together with Lance Corporal Podszus put it out of action. . . . We seize the next bunker from the rear. I fire an explosive charge. In a moment the force of the detonation tears off the rear part of the bunker. We use the opportunity and attack the occupants with hand grenades. After a short fight, a white flag appears. . . . Encouraged by this, we fling ourselves against two additional small bunkers, which we know are around 100 metres to our half left. In doing so we move through a swampy area, so that we must temporarily stand in the water up to our hips.

In the end Rubarth and his men were able to destroy seven bunkers. There was no sign of the French ‘interval’ troops who ought to have been guarding the flanks of the bunkers but had possibly taken cover from the German bombers. By the evening Rubarth, having suffered six casualties out of his original eleven men, had reached the ground above Wadelincourt. For this achievement he was later awarded the Knights cross of the Iron Cross.

The most vital sector of the Sedan crossing point was assigned to the 1st Panzer Division, which was to cross at the village of Glaire just west of Sedan, at the base of a small peninsula formed by a loop in the river. As the troops hurled hundreds of rubber boats into the river and jumped after them, many were killed by French gunfire, but enough reached the other side to rush the French defences. Particularly spectacular results were achieved by troops of the 1st German Infantry Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Hermann Balck. A tough veteran of the Great War, in which he had been wounded five times, Balck was an exceptionally inspiring commander who was to end the war as an army group general. Having succeeded in crossing the river, Balck and his men found four French bunkers in their path. They bypassed one; two others succumbed relatively easily (and indeed may have been abandoned by their defenders); and the fourth held out for about three hours. By 7 p.m. Balck’s men had covered the 2.5 km from the Meuse to the Château of Bellevue; three hours later they had reached the village of Cheveuges, about 3 km further south. Already by 5.30 p.m. the German foothold on the left bank was sufficient for engineers to begin building a bridge; meanwhile rafts ferried over equipment; by 11 p.m. a bridge capable of bearing a weight of 16 tons was ready, and the first tanks started to cross.

Of the three German divisions at Sedan, it was the 2nd, taking the righthand prong of the attack at the village of Donchery, which had the hardest task crossing. The Germans came under intensive French artillery fire from the opposite bank. Most of the boats were destroyed, and only one officer and one man managed to get across. They both promptly swam back. Only when the 1st Division had established a foothold on the other side was it possible for elements of the 2nd Division to cross at about 10 p.m. It was not possible to start constructing a bridge until 9 a.m. on the morning of 14 May, and continued French artillery fire meant that it took 20 hours to complete. Once fully across the river, however, the 2nd Panzer Division was to assume a major strategic significance, since it found itself directly attacking the hinge between the French Ninth and Second Armies.

By the end of the day (13 May) the Germans had succeeded in crossing at Sedan in three places. Despite pockets of fierce resistance, the French defence overall, weakened by the aerial bombardment, was unimpressive. During the afternoon, some soldiers of the 55DI had begun to flee their positions. In the evening this developed into a full-scale panic. As well as crossing at Sedan, the Germans had breached the Meuse at two other localities. In fact the first German troops to cross the river on 13 May did so not at Sedan but at the little village of Houx, about 4 km north of Dinant. Troops from Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division had crossed by stealth at night along an old weir that connected an island to the two banks of the river. This sluice had not been destroyed by the French for fear that it might excessively lower the level of the river. Thus, some of Rommel’s soldiers were on the other side of the Meuse by the early hours of 13 May.

The main attack by Rommel’s troops occurred later that morning. They were helped by the fact that two of Corap’s divisions, the 18DI and the 22DI, were still not fully in position. Neither of them was motorized. The 22DI had to cover 85 km on foot to reach the Meuse and only arrived there on 13 May after three consecutive night marches. As for the 18DI, which had slightly further to go, French planning had only required it to be fully in place by the morning of 14 May. Those troops in position by 13 May were tired from their march, and four battalions had yet to arrive. Furthermore, the Houx crossing point happened to be at the junction of these two divisions. Despite all these weaknesses, the French defenders fought hard, and the Germans might not have succeeded in crossing had it not been for Rommel’s inspiring leadership and resourcefulness. Rommel ordered houses upstream of the crossing point to be set alight in order to provide a smoke-screen. When German engineers seemed momentarily unnerved by machine-gun fire coming from the French side of the river, Rommel called up tanks to provide covering fire. In responding, the French were handicapped by their shortage of anti-tank weapons. At one point Rommel himself took direct command of a battalion and crossed the Meuse on one of the first boats, joining the men who had been there since the early morning.

The most difficult of the three German crossings on 13 May was that undertaken by Reinhardt’s XLI Panzer Corps at Monthermé (about 32 km north of Sedan). Here the Meuse flows faster than at Sedan and cliffs plunge down to the river. On the west side, where Monthermé lies in a small isthmus, the ground rises up steeply again. This provides a superb defensive position. At the end of 13 May, the Germans had crossed the river but only succeeded in establishing a tiny bridgehead. The French defenders, who were regular troops, fought hard, and the Germans were not yet able to bring tanks across the river.

By the end of the day, then, three German bridgeheads had been established— one of about 5 km at Sedan, one of less than 3 km at Houx, and one of barely 1.5 km at Monthermé. At last the French realized the gravity of the situation. Arriving at 3 a.m. on 14 May, with Doumenc, at Georges’s headquarters, General Beaufre witnessed the despair of the French High Command:

The room was barely half-lit. Major Navereau was repeating in a low voice the information coming in. Everyone else was silent. General Roton, the Chief of Staff, was stretched out in the armchair. The atmosphere was that of a family in which there has been a death. Georges got up quickly and came to Doumenc. He was terribly pale. ‘Our front has been broken at Sedan! There has been a collapse . . .’ He flung himself into a chair and burst into tears.

He was the first man I had seen weep in this campaign. Alas, there were to be others. It made a terrible impression on me.