After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the Army extended its frontier boundaries west of the Mississippi. Throughout the 19th century, the United States established a wide variety of different installations. Post is a general term for any installation where troops are “posted.” Eventually, cantonment came to mean a temporary encampment, as it would in World War I, and the designation of fort meant a permanent facility. (While the term Army base is used by civilians on occasion, the American military does not use this designation.) For the greater part of the 19th century, however, there were no hard and fast rules regarding terminology. Some permanent sites were initially called cantonments, others were designated as forts even though they were known to be very temporary affairs.

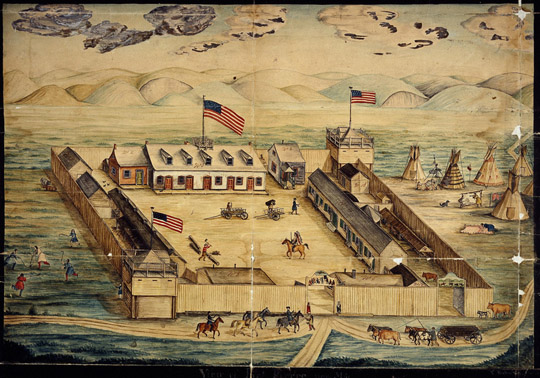

Between 1804 and roughly 1845, the Army constructed posts in front of the advancing white settlers, thus maintaining a buffer between settlers and Native Americans. By 1845, 24 of the Army’s 56 military posts were west of the Mississippi. After the Mexican War, westward migration accelerated and keeping whites and Native Americans separate was no longer possible. For the next 40 years and with the notable exception of the American Civil War, the Army would serve as a constabulary, primarily focused on controlling the Native American population. Forts sprung up at major settlement areas in Texas, Oregon, New Mexico, and California. Outposts were also established along the various migration, trade, and communication routes. The Army established many permanent installations in the two decades after the American Civil War, the period of the major Indian wars in the West.

From the 1880s until the Spanish–American War, the Army focused on the oversight of Indian reservations, thus lessening the need for small posts and outposts sprinkled across the West. Many interior facilities were closed and greater emphasis was placed upon coastal defense fortifications as the nation increasingly interested itself in world affairs. Interior posts that remained open could oversee larger areas because of improvements in transportation and communication. Although the days of the frontier post were numbered, some had already grown into major installations and therefore survived into the modern era: forts Leavenworth, Bliss, Riley, Sill, and Sam Houston, and Jefferson Barracks.

At the beginning of war with Spain in 1898, the Army occupied 78 posts across the nation. The exigencies of war would force the abandonment of some western posts (reduced to 66 by 1902); others were maintained with small caretaking units. The War Department designated temporary training encampments in Virginia, Georgia, and Florida, all of which soon came under close scrutiny because of poor administration, lack of provisions, and high mortality from typhoid fever (often misdiagnosed as malaria), and poor sanitary conditions.

During the winter of 1898 to 1899, the War Department designated several temporary holding camps for soldiers preparing to rotate through occupation duty in Cuba and Puerto Rico. These camps, primarily in the foothills of the southern Appalachians, proved to be very successful in terms of function and health. Many of the southern locales selected in late 1898 would become America’s military towns in the 20th century.