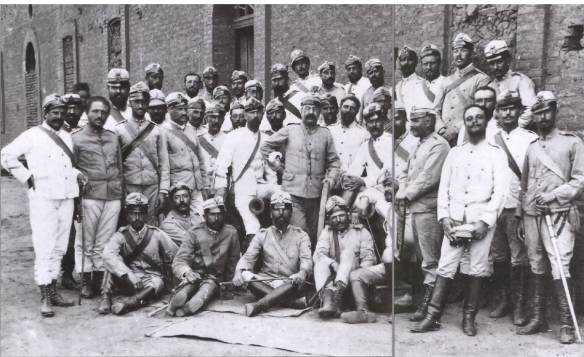

GENERAL BARATIERI AND ITALIAN OFFICERS.

General Baratieri’s reputation was tarnished by the defeat at Adowa. He favoured a Fabian strategy against Menelik, but pressure from his officers and Prime Minister Crispi led to the debacle.

The Battle of Adowa: 1 March 1896 – The Approach

Baratieri’s advance into Tigre province was initially successful, and he established several garrisons there. His confidence that Menelik could not possibly move north in any real force was shattered in December 1895, when the emperor’s advance guard of 30,000 overran an askari contingent of 2000 at Amba Alagi, and besieged the survivors, who took shelter in a fort at Makalle. By January, Menelik offered terms to Baratieri, who took this act as a sign of weakness. Moreover, Francesco Crispi, the Italian prime minister, demanded Baratieri press on.

The Italian general used the delay produced by negotiations to concentrate his army near Adigrat. The rough terrain offered an excellent defensive position. He was quite confident that he could hold his own against a concerted attack by Menelik, if the discussions broke down. Indeed, Baratieri realized the size of the Ethiopian army was a potential problem for Menelik, and intended to use time to his advantage. His own supply line from Massawa was only 240 km (150 miles) in length. And although his army was not adequately equipped with animals and wagons, Menelik’s army suffered even more greatly from its overextended position, and was overburdened with the logistical problem of feeding 100,000 men. Baratieri wanted to wait out the Ethiopian emperor, hoping starvation and lack of water would defeat his enemy. If Menelik decided to attack, his position afforded him security.

Baratieri’s strategy was quite sound, but incessant telegrams from Rome demanded results. Crispi’s patience had worn out. His political opposition had made gains in the public eye as a result of earlier military defeat.The prime minister, frustrated by Baratieri’s seeming intransigence, dispatched General Baldissera to assume command of the army and bring the campaign to a victorious conclusion. Baratieri caught wind of his imminent dismissal, and under pressure from his generals, excluding Albertone, recommended an assault on Menelik’s apparently decrepit army. The supply situation had not yet reached a crisis point for the Italians. Baratieri did place his men on half rations, but they were eating like kings compared with the serious problems the Ethiopian army was experiencing. Nonetheless, the thought of retreating into Eritrea or waiting for his replacement did not seem an honourable alternative to Baratieri. Thus, at nightfall on 29 February 1896, Baratieri ordered his army forward from their camp at Sauria towards Menelik at Adowa.

Generalship

Generalship in the age of colonial empires required a skilful leader, flexible and creative enough to use effectively what forces and resources he had at any moment. The nature of wars of empire was that there were never sufficient troops, or an abundance of supply. The terrain was often inhospitable, and the local populations hostile. The conclusion of a general peace in 1815 meant that the majority of military experience during the nineteenth century would be found beyond the Continent. The Crimea, Italy, Austria and France were campaigns of relatively short duration and extremely violent, but limited within the scope of accepted European standards.

Wars of empire involved the domination of peoples and the transformation of indigenous societies. Local resistance to European expansion was fierce, and wholehearted, and European reprisals were equally nasty. The Germans pursued a particularly devastating Vernichtungskrieg, or war of annihilation, against the Herero in 1904-05. Wars of empire often led to extremes, out of cultural imperatives or military necessity. The result, however, was that while military service overseas was an exception at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was a requirement for promotion and command on the European continent by the turn of the century. The tactics developed, the traditions established and the methods of war-making were inexorably influenced by this century of colonial wars. They would be tested, however, and fail in Flanders fields and elsewhere in 1914.