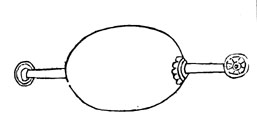

“Thunderbolt-ball”

Zeng Gongliang and Ding Du, Wujing zongyao, late Ming (Wanli Period) edition, in Zhongguo bingshu jicheng, Volume 3 to 5, edited by the Zhongguo bingshu jicheng Editing Committee (Beijing and Shenyang: Jiefangjun chubanshe and Liaoshen shushe, 1988), 12:59 (p.640).

Projectiles using low-nitrate gunpowder were effective vehicles for incendiary attacks, but would not cause an explosion. These fire-balls (huoqiu) were containers of low-nitrate gunpowder thrown by trebuchet with the intention of directing fire attacks on to enemy targets. This was a useful and effective weapon that, though actual explosive bombs came into use in the first half of the eleventh century, continued in use beyond the seventeenth century (or at least continued to be mentioned in military manuals). The Complete Essentials from the Military Classics contains descriptions of both fire-balls and grenades/bombs. The distinction between a grenade and a bomb is modern; pre-modern Chinese sources do not separate explosive projectiles by size or delivery system (with the exception of occasional references to the ‘‘hand bomb,’’ shoupao). Accordingly, I will use ‘‘bomb’’ as the overall term to describe these explosive projectiles.

Two changes in design made fire-balls into bombs: increasing the percentage of saltpeter, and placing the mixture in a rigid receptacle capable of temporarily containing the expanding gases when ignited. The bomb exploded when the force of expanding gases exceeded the ability of the receptacle to contain them. This happened very quickly, and a much stronger explosion could be achieved by using a stronger receptacle. The thunderclap bomb (pili huoqiu or pili pao) described in the Complete Essentials from the Military Classics used a bamboo receptacle. The anti-personnel effects of the explosion were enhanced by the addition of shrapnel to the gunpowder mixture inside the receptacle. This was more important when the receptacle was bamboo or wood, rather than iron. Given the apparent timing of the development of the bomb with its added shrapnel, it is possible that this contributed to the practice of putting shrapnel in the gunpowder tube of fire-spears to enhance their anti-personnel abilities. If this is the case, then there must have been considerable cross-fertilization between early gunpowder weapons leading up to the invention of the true gun.

Thunderclap bombs were used in the defense of the Song capital when the Jurchen attacked in 1126–7. Despite the use of such a powerful weapon, Song defenses were ultimately overwhelmed and the capital fell. The main reason the defenses failed was insufficient troops to man the walls, so the effect of the bombs is hard to measure. Yet even these early weapons were obviously useful. It may well have been that the supply of bombs was still limited, and the most effective tactics for using that small number had not been worked out. The supply of weapons directly affects their use, and at least one account of the siege indicates that the original commander of the defenses was reluctant to expend his artillery ammunition and bombs. He was sacked, and the new commander, Li Gang, ordered the soldiers to fire at will. Li, who recounted the incident, may have felt justified in his actions, but he may have also been incompetent.

The final step in the development of the bomb came with the use of an iron receptacle. This required a higher percentage of saltpeter in the gunpowder to shatter the casing, and resulted in a much more powerful explosion. The first mention of a gourd-shaped, cast iron bomb is at the Jin siege of the Song city of Qizhou in 1221, though the name ‘‘thundercrash bomb’’ (zhentianlei) was not recorded until a naval battle in 1231. By 1257, a Song official was complaining that the arsenals of two cities facing the Mongol border, which should have had ‘‘several hundred thousand iron bombshells,’’ had only 85 in one of the cities, along with 95 fire-arrows (or rockets), and 105 fire-spears. He also pointed out that in other places one arsenal produced one or two thousand iron bombshells a month, and that ten to twenty thousand at a time were sent to some major cities. We see here not only the rapid adoption of an effective weapon, but also a revolutionary change in military practice requiring the mass manufacturing of the new weapon.