Battle of Guastalla

In February 1733, Augustus of Saxony, king of Poland, died. Poland was an elective monarchy and both Louis XV of France and Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, proposed their own candidates. Vienna supported Augustus III, the elector of Saxony; Versailles wanted a former king of Poland, Stanislas Leszczynski, father-in-law to Louis XV. Neither could compromise on a candidate and war erupted. France prepared two armies and a separate expeditionary corps dispatched by sea to Poland, while the armies marched against Austria using the same routes as previous wars: the Bavarian Plateau and northern Italy.

Spain allied itself to France through a Bourbon family compact. The Spanish crown wanted to reclaim southern Italy and, if possible, Milan. Both had been part of the Spanish empire prior to 1715, but the Peace of Utrecht removed them from the Spanish Bourbon realm.

Queen Elizabeth Farnese had two sons by Philip V. As the king had two sons through his first marriage, she wanted to secure their future by giving each a crown. The eldest, Charles, received the Duchy of Parma, after last duke’s death in 1730, but with the new war her plans changed. Philip, at the queen’s behest, appointed Charles commander of the Spanish army in Italy. His objective was the reconquest of the Kingdom of Naples.

France, however, needed the support of the Piedmontese to cross the Alps and invade Milan. Charles Emmanuel III of Savoy, who ascended to the Piedmontese throne after his father Victor Amadeus left him the crown in 1730, waited for an opportunity to resume his family’s traditional policy of expansion in northern Italy. France promised him the Duchy of Milan in return for his aid. He accepted the French proposal and in a few days Piedmontese troops occupied western Lombardy, entered Milan, and besieged its citadel. Concomitant with Franco-Piedmontese operations, the Spanish army passed through the Papal States and entered Naples.

Having assessed the situation and observed no significant alterations to global European policy, Venice chose neutrality rather than take sides. The republic recalled many regiments from its Dalmatian garrisons and prohibited the movement of foreign armies through its territory. The emperor, however, needed right of passage for his forces. He had quickly prepared three weak armies. The first in Germany, superbly commanded by Prince Eugene, maneuvered so well that the French could not leave the right bank of the Rhine; and the Bavarians did not have the courage to declare war without the support of a French army.

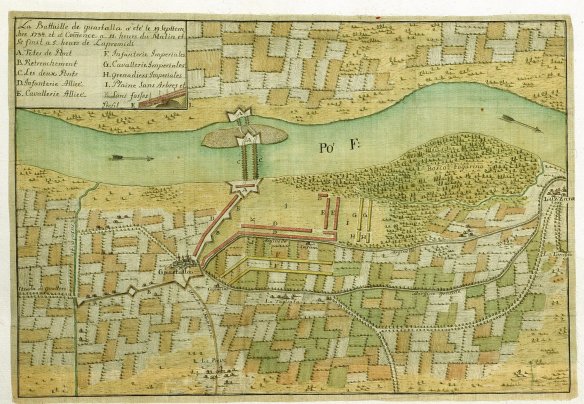

The second Imperial army-roughly ten thousand men-was in Naples and clearly unable to adequately defend the kingdom. The third, under the count of Mercy, came from Austria to northern Italy in the spring of 1734. Its strategic task was to reach Naples, to support local troops, and destroy the Spanish army. The Franco-Piedmontese army led by Charles Emmanuel III made it impossible. Allied troops defeated the Austrians twice: in Parma in May and, later, on September 19, 1734, near Guastalla. These victories allowed the Spaniards to defeat Austrian troops at Bitonto. The Kingdom of Naples was conquered and Philip V presented it to his son Charles, who became Charles VII of Naples and who-later, after his father’s and his two older half-brother’s deaths-became King Charles III of Spain.

In January 1735, Charles VII landed in Sicily with his army. The island was conquered as quickly as the Kingdom of Naples had been. Subsequently, the Spanish army marched north to reinforce the French in the Milanese, but the fighting ended prior to their arrival. Austria approached France looking to negotiate; and the French accepted. An armistice was signed and, after a couple of years of discussions, peace came.

The elector of Saxony, Augustus III, received the Polish crown. His competitor, Stanislas Leszczynski, received the Duchy of Lorraine, which belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. At his death, Lorraine passed to his daughter, the queen of France. Duke Francis of Lorraine received compensation through his marriage to the daughter and heir of the Emperor Charles VI, Maria Theresa. He also received Tuscany, whose ruling family, the Medici, had nearly died out, as the last grand duke had no heirs.

Spain maintained its conquests as long as they remained under Charles VII and independent of Spain. Thus, Spain returned to Italy.

Austria and Britain found this settlement quite problematic. Tuscany was insufficient to balance the geopolitical shift in Italy. In order to maintain the equilibrium in Italy, the general agreement returned Lombardy to the House of Habsburg instead of to Charles Emmanuel of Savoy. Obviously, the king of Sardinia had insufficient resources to forcefully object, particularly after the French approved the terms. His delusions of grandeur failed to become manifest, but a new opportunity was on the horizon.