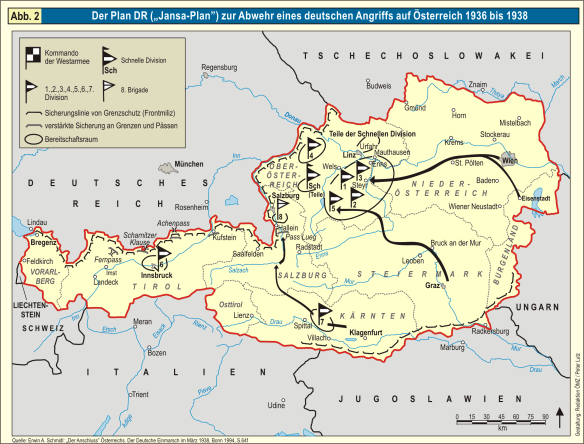

The Plan DR (known as Jansa Plan). Deployment of the Austrian Army as March 11, 1938.

The Austrian Bundesheer, consisting of seven infantry divisions, one independent brigade and one armored division, was a developing army in March 1938. As such, it faced shortages that would have compromised a sustained Austrian resistance of more than several weeks. The most egregious of these was the lack of artillery ammunition both in the infantry divisions and in the independent artillery regiment, which amounted to approximately a ten to twelve day supply. This might have been extended through the careful conservation of shells as practiced by all armies when short of ammunition; nevertheless, after the ammunition was depleted it would have had a highly negative effect upon the defensive capabilities of the Bundesheer. The Austrian army was also not as well trained as the Wehrmacht.

Although the Bundesheer’s artillery regiments were still equipped with large numbers of World War I vintage artillery, these had been modernized though the use of new ammunition and technical refinements that together had extended both lethality and range. The equipment had also been lightened for use in the mountainous terrain of Austria. Here, for example, the 80 mm field cannon (World War I vintage) proved very effective. Since the Wehrmacht was experiencing problems moving its artillery into Austria exactly because it had not considered the problems that mountainous terrain might pose, it is possible that the first days of the invasion would have actually given Austria an important, if temporary, advantage in artillery.

Most important for defense against German armor was the Austrian-made 47 mm anti-tank cannon which could easily penetrate the armor of any German tank at that time at over 1000 m. By March 1938, the Bundesheer deployed 270 of these guns with more than enough ammunition to decimate the armor of the Eighth Army.

From the first moment of the invasion of Austria, frictions arose for the Wehrmacht that mounted one on top of another. Officers and men arrived late to their posts and were mis-assigned or simply untrained for their duties. Wagons and motorized vehicles were frequently missing, inadequate for their tasks or unusable. Indeed, the German VII Army Corps alone described its supplementary motorized vehicle situation as “nahezu katastrophal” (almost catastrophic), with approximately 2,800 motorized vehicles which were either missing or unusable. Nor was the situation any better regarding horses, the prime mover of the Wehrmacht. Once inside Austria, the difficulties were aggravated through a completely inadequate road and rail network and the huge numbers of men and materiel attempting to push through. Poor discipline, lack of training, and outright incompetence worsened matters, as did mechanical breakdowns and lack of fuel. The result was that divisions, regiments, and battalions were completely torn asunder; they ceased to be combat units. Like some great malfunctioning clockwork, the Wehrmacht lurched and shuddered towards the Austrian capital. Only a few parts of it finally grated to a halt in the suburbs of Vienna one week later. Even this dismal performance was only possible due to vital and essential assistance rendered to the Wehrmacht by Austrian gas stations, and shipping and rail services. Without this help, Hitler’s victory parade on the Ringstraße would have been conspicuously devoid of German troops and armor. Nevertheless, as with the North Vietnamese Tet Offensive thirty years later, operational disaster does not equal military disaster. The Nazi propaganda machine, parts of which were busy running down German soldiers in their rush to get to Vienna on 12 and 13 March, would prove as successful as it had ever been.

Austrian defense plans, as set down in the “Jansa Plan”, anticipated a German assault and had been begun in the fall of 1935 by Austrian Chief of the General Staff Alfred Jansa together with his divisional commanders. They provided not only for the mobilization and deployment of the entire Bundesheer and auxiliary formations against the Wehrmacht, but also for the creation of street blockades and the destruction of bridges and roads in order to hamper the advance of the German army. The mobilization required a minimum of four days for the active army.

As recently stated in the journal of the Austrian Armed Forces (cf. Angetter, op. cit.), the defensive concept Head of General Staff Alfred Jansa had elaborated by 1935 was known to German military command as soon as in 1936. Moreover, Jansa was retired prior to the “Anschluss”, namely in February 1938 (as required by Hitler in the Berchtesgaden Agreement). His successor, General Wilhelm Zehner, a declared opponent of National Socialism, was set to carry out the plan, but was put on hold by Schuschnigg. The author comes to the conclusion that the Austrian Bundesheer would not have had the capacity to resist the Wehrmacht but would have been dependent on help from outside the country.

There was no way the Austrian army could have prevailed. The Bundesheer would have fired a few shots which would have been of symbolic value but this would have been negated by an uprising of Nazis in Styria and Salzburg where they were reasonably strong. So it would have been a very mixed picture with unnecessary loss of life; Austria would have disappeared from the map anyway. Schuschnigg was right to order the army to stand down.

As to the question of military resistance by the Bundesheer as a function of its penetration by the Nazis, the best scholarship on the matter, by Erwin Steinböck, Erwin Schmidl and myself indicates that the Nationalsozialistische Soldatenring (the name of the Nazi organization which attempted to penetrate and undermine the Bundesheer) never amounted to more than 5% of the rank and file, and perhaps half of that among the officer corps. This was, in no small part, due to the ruthless suppression of the Nazis by the Schuschnigg government 1934-1938. The evidence I have examined in Vienna shows fairly clearly that the army would have fought, and that any discovered traitors would have been purged quickly. Might that have lessened the BH’s effectiveness? The best answer is “perhaps”; but given the nature of the military and the broader issues of national defense, I doubt that the Nationalsozialistische Soldatenring would have amounted to much in the case of the Austrian state mounting a military defense against a Nazi German invasion.

References:

Daniela C. Angetter, “Kommentar: Wehrfähigkeit – Wehrwilligkeit in Österreich 1938”, in Truppendienst 302 (2/2008), URL.

Ernst Hanisch, Nationalsozialistische Herrschaft in der Provinz: Salzburg im Dritten Reich, Salzburg 1983.

Alexander N. Lassner, “The Invasion of Austria in March 1938: Blitzkrieg or Pfusch?”, in Günter Bischof / Anton Pelinka / Günter Stiefel (eds.), The Marshall Plan in Austria (Contemporary Austrian Studies, vol. 8), New Brunswick et al. 2000, p. 447-486, extract quoted from p. 463f.