With its geographic position in Europe and relatively defenseless borders east and west, Germany’s worst strategic nightmare was always the two-front war. To avoid this trap, German military thinking focused on conducting short wars that would be won by a single decisive battle. Thus, sequential effects and extended operations in time carried a low priority in German thinking. And since logistics is the critical enabler of any extended period of operations, the Germans never developed the robust logistics structure or the adequate logistics doctrine needed to carry them through a long war. But a long war on even more than two fronts is exactly what the Germans ended up fighting twice in a 30-year period.

Despite their rapid movements and deep armored thrusts, the German Blitzkrieg battles of World War II were not true operational campaigns but rather were tactical maneuvers on a grand scale. Blitzkrieg did feature the innovative use of combined arms tactics aimed at achieving rupture through the depth of an enemy’s tactical deployment, and it did exhibit many of the features we now associate with the operational art. It also focused far too heavily on annihilation and rapid decision by a single bold stroke.

On the tactical level of war, the German Army was superior to the Red Army on almost every count, yet the Soviets still beat the Germans in the end. German tactics were innovative and flexible, and their leaders and soldiers were well trained and exhibited initiative down to the lowest levels. Soviet tactics were largely rigid, cookbook battle drills, with the soldiers and the lower-level leaders functioning as mere automatons. But the Soviets had developed a far superior concept of the operational art and especially the principles of depth and sequential effects. The Soviets became masters of striking deep into the German rear to disrupt command and control systems and the all-too-fragile German logistics system. In the end, Blitzkrieg was little more than the German Army’s tactical response to German chancellor Adolf Hitler’s totally incoherent strategy.

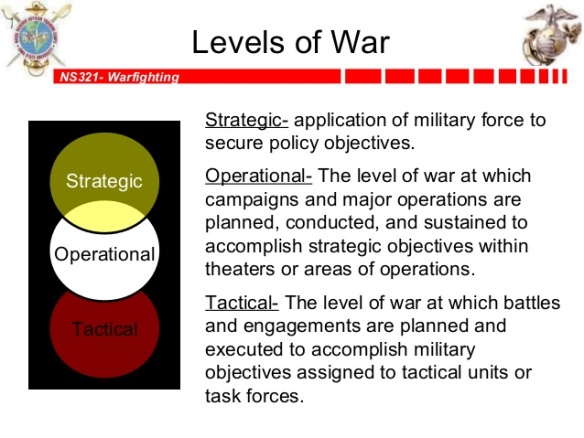

Despite the flaws in what eventually became Blitzkrieg, the post-World War I German Army did have a clear, albeit imperfect, understanding of a level of war between the tactical and the strategic. Writing in 1920, General Hugo Freiherr von Freytag- Loringhoven noted that among German General Staff officers, the term Operativ was increasingly replacing the term Strategisch to “define more simply and clearly the difference from everything tactical.” The 1933 edition of Truppenführung, the primary German war-fighting manual of World War II, distinguished clearly between tactical and operational functions. Truppenführung’s principal author, General Ludwig Beck, considered Operativ a subdivision of strategy. Its sphere was the conduct of battle at the higher levels, in accordance with the tasks presented by strategic planning. Tellingly, when U. S. Army intelligence made a rough English translation of Truppenführung just prior to World War II, the term Operativ was translated throughout as “strategic.”

Post-World War II American military doctrine focused almost exclusively on the tactical level. Although the U. S. Army and its British allies had planned and executed large and complex operational campaigns during the war, the mechanics of those efforts were largely forgotten by the early 1950s. Nuclear weapons cast a long retarding shadow over American ground combat doctrine, and the later appearance of battlefield nuclear weapons seemed to render irrelevant any serious consideration of maneuver by largescale ground units. The Soviets, meanwhile, continued to study and write about operational art and the operational level of war. While the U. S. military intelligence community closely monitored and analyzed the trends in Soviet doctrine, American theorists ignored or completely rejected these concepts. Because of its dominant role in NATO, America’s operational blinders were adopted for the most part by its coalition allies.

In the early to mid-1970s, American thinking began to change. The three major spurs to this transformation were the loss in Vietnam, the stunning new weapons effects demonstrated in the October 1973 Yom Kippur (Ramadan) War, and the need to fight and win against the superior numbers of the armed forces of the Warsaw Pact. The concept of the operational level of war entered the debate when the influential defense analyst Edward Luttwak published the article “The Operational Level of War” in the winter 1980-1981 issue of the journal International Security. About the same time, Colonel Harry Summers’s book On Strategy: The Vietnam War in Context sparked a parallel renaissance in strategic thinking and the rediscovery of Clausewitz by the American military. The U. S. Army formally recognized the operational level of war with the publication of the 1982 edition of FM 100-5, Operations, which also introduced the concepts of AirLand Battle and Deep Battle.

The operational art was first defined in the 1986 edition of FM 100-5, along with the concept that commanders had to fight and synchronize three simultaneous battles: close, deep, and rear. The idea was that one’s own deep battle would be the enemy’s rear battle, and vice versa. The close battle would always be strictly tactical, but the deep and rear battles would have operational significance.

During the 1970s and 1980s the American military invested heavily in new weapons systems, force structure, and training to complement its evolving doctrine. The U. S. Army acquired such advanced systems as the M-1 Abrams tank; the M-2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle; the UH-60 Blackhawk airmobility helicopter; the AH-60 attack helicopter; and the M-270 multiple launch rocket system (MLRS). U. S. Air Force systems included the A-10 attack aircraft, specifically designed to kill tanks; the F-15 air superiority fighter; and the F-16 multirole fighter. The air force also developed a sophisticated array of precision-guided munitions for the various platforms. Most importantly, however, the United States committed extensive resources to developing its military manpower, producing officers, noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and enlisted men capable of operating the complex systems, exercising initiative, and making independent judgments and decisions in extremely stressful situations.

This superbly trained and equipped force with its new and sophisticated operational doctrine was never committed against the primary enemy it was designed to fight, the massed tank armies of the Soviet Union. That enemy largely disappeared with the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union. But as that was happening, Saddam Hussein of Iraq committed the strategic blunder of invading Kuwait. Believing he could bluff the Americans and their allies, Hussein then compounded his error by allowing his enemy the time to build up an overwhelming force in Saudi Arabia, prior to launching a counterattack through Kuwait and into Iraq itself.

The irony, then, is that even though the doctrine of AirLand Battle, heavily based on the concept of the operational art, was never tested against the Soviets, it did prove devastatingly effective against a Soviet surrogate, the Iraqi Army, armed with Soviet weapons and equipment and trained in Soviet doctrine. The lopsided victory of the ground phase, the so-called Hundred Hour War, was not, however, quite the same thing as defeating the Red Army. Although the American weapons vastly overmatched those of the Iraqis, Hussein’s forces for the most part were not equipped with top-of-the-line Soviet systems. Also, the rigid and highly centralized command and control system, the officer corps conditioned to follow orders to the letter but not to exercise initiative, and the poorly trained individual soldiers that were all too typical of most Middle Eastern armies only compounded the Iraqi catastrophe.

Twelve years later, in 2003, Hussein’s army had not been rebuilt to anywhere near the level it had been at in 1991, and this time the victory was even more lopsided, as the Iraqis were crushed by a significantly smaller American force. But rather than just defeating the Iraqi Army as they had done in 1991, the Americans this time sought to occupy the country and change its regime. The U. S. military had gone in with just enough forces to win the battle but not nearly enough forces to secure the peace. That, plus a series of key errors and poor decisions during the early phases of the occupation, resulted in an insurgency that killed many more American soldiers than the initial combat operations. Thus, although the Americans conducted the initial phase of the Iraq War with operational near-perfection, their overall strategy was significantly flawed by a failure to connect operational success with the overall strategic objectives. Ironically, this strategic incoherence was precisely the mistake the Americans had made in Vietnam.

References McKercher, B. J. C., and Michael A. Hennessy, eds. The Operational Art: Developments in the Theories of War. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996. Naveh, Shimon. In Pursuit of Military Excellence: The Evolution of Operational Theory. London: Frank Cass, 1997. Newell, Clayton, and Michael D. Krause, eds. On Operational Art. Washington, DC: U. S. Army Center of Military History, U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. Zabecki, David T. The German 1918 Offensives: A Case Study in the Operational Level of War. New York: Routledge, 2006. Zabecki, David T., and Bruce Condell, eds. and trans. Truppenführung: On the German Art of War. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2001.