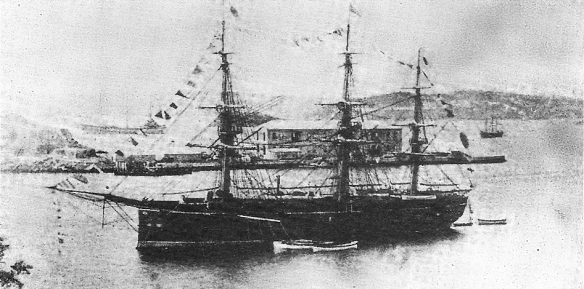

The Ryūjō was the flagship of the Taiwan expedition.

1896 map of Formosa, revised by Rev. William Campbell

A shipwreck in 1871 on Taiwan (Formosa) involving sailors from the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa) grew in seriousness between that year and 1874, until it developed into a full-blown crisis between China and Japan. Japanese sailors from the Ryukyu Islands were marooned on Taiwan in 1871 as a result of a shipwreck. Some of the sailors were killed by native Taiwanese aboriginals. Japan, arguing that the Ryukyu Islands acknowledged Japanese suzerainty because residents paid tribute to Japan, claimed that the murdered sailors were subjects of the emperor and demanded that China provide some form of compensation or other redress for the actions of the Taiwanese aborigines. The Qing government, which, like Japan, also received tribute from the rulers of the Ryukyu Islands (Liujiu in Chinese), took no action. The dispute, therefore, went unresolved for a number of years.

Under pressure from militarists in Japan to resolve the matter, the Japanese government sent a naval expedition to Taiwan in 1874. At that time, the Qing dynasty had two officials who dealt with maritime and international matters: the commissioner of trade in South China, based in Nanjing, and the northern commissioner of trade in Tianjin. Although both positions had been created by the Qing Court to attend to issues involving foreign relations and to meet China’s responsibilities relating to the Treaty of Tianjin, neither official had responsibility for coastal defense. At the time the crisis developed, Li Hongzhang was concurrently governor-general of Zhili and northern commissar of trade. Li Zongxi was southern commissioner of trade in Nanjing. The Qing Court directed both officials to address the Japanese threats, but it was Li Hongzhang who actually took action.

In early 1874, Japan sent a force of 3,600 troops and three ships to Taiwan to deal with the matter. Li Hongzhang, in response, recommended to the Qing Court on May 10, 1874, that the superintendent of the Fuzhou Dockyard, Shen Baozhen, be dispatched to Taiwan with troops and ships in response to the Japanese actions. The Chinese fleet, at the time, was not concentrated in a naval base, nor had it trained for naval action. Instead, the ships were distributed along the coast, where they tried to control piracy. Another reason the fleet was dispersed was to distribute the cost of maintaining the ships and their crews to local officials, reducing expenses for the Qing government. As a consequence of this dispersion, Shen had a great deal of trouble assembling a fleet. Moreover, Shen was hampered by faulty intelligence. He believed that Japan had a fleet of steam-powered ships and two ironclad steamers. Shen’s own ships were all made of wood.

By July, Shen Baozhen still had not reacted to the Japanese naval force. He asked for ships and troops from the northern and southern commissioners, seeking to assemble 19 ships and a credible force of troops. By September 1874, however, he had gathered only 6,500 troops from the Anhui Army and seven steamships, all supplied by Li Hongzhang. He sent these forces to the Pescadore (Penghu) Islands, where he had gathered another 6 ships. He also got a battalion of troops from Hubei Province, which he sent to the Pescadores by ship. By November 1874, after six months of effort, Shen assembled a force of 10,000 troops and 16 ships in the Pescadores. However, at no time had he taken any action to intercept the Japanese fleet or any Japanese ships on their way to Taiwan.

By the end of 1874, rather than risk war, the Qing Court settled the matter with the Japanese. China paid a monetary indemnity to Japan, which tacitly recognized Japan’s claims to the Ryukyu Islands. Japan, in response, withdrew its forces from Taiwan. The Formosa Crisis of 1874 had the effect of focusing China’s attention on its need for a credible, effective fleet unified into a navy. The northern and southern commissioners, from that time on, assisted by Prosper Giquel, who figured prominently in the Taiping Rebellion, were part of the self-strengthening movement. They ordered a number of cruisers and gunboats from foreign shipyards and established a “Sea Defense Fund.”

REFERENCES James P. Baxter, The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933); John L. Rawlinson, China’s Struggle for Naval Development, 1839- 1895 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967).