The Macedonian solution to the problem of flank vulnerability was to create two modified forms of the phalanx, the articulated phalanx and the double phalanx. The articulated phalanx may have been introduced by Pyrrhus in his wars against the Romans (281-275 b. c. e.). The idea was to make the phalanx more flexible by compensating for its tendency to spread out and create gaps between its component battalions. Companies of sarissa -carrying phalangites were interspersed with companies of lighter-armed and more loosely organized units. These units acted as flexible joints connecting the various battalions to the main body when the phalanx began to spread. The idea may have been derived from Alexander’s use of the hydaspists that acted as connecting joints between his cavalry and the main body of the phalanx.

Yet another way of protecting the flanks and rear of the phalanx was to use the double phalanx. The main phalanx was protected by a reserve line, sometimes a double line, of phalangites deployed behind or to the rear oblique of the main body. This formation was probably first used in 222 b. c. e. at the battle of Sellasia. While the articulated phalanx and the double phalanx represented workable solutions against another infantry phalanx, they were poor compromises to solving the problem of cavalry attack against the phalanx. In the end the problem of the phalanx’s vulnerability was never satisfactorily solved.

It might be added that the quality of the phalanx infantryman under the Macedonians had fallen considerably when compared with the soldiers who had fought under Alexander. The truly national army of Alexander comprising men with long terms of service that produced discipline and cohesion ceased to exist under Alexander’s Successors. Even in Macedonia, the most nationally conscious of all the Successor states, the system was impossible to maintain. It cost too much and took manpower from the land and economy, just as it had during the period of the early city-states. Now, however, there was no treasury of conquest to finance the military system.

The national army motivated by patriotic fervor and long professional experience disappeared under the Macedonian Successors. It was replaced by a small national force comprising mostly mercenaries, who served full time in return for the promise of a farm on retirement. These mercenaries were also used as garrison forces throughout the empire and could be called to service in times of trouble. The Macedonian army, in essence, went back to what it had been before Philip and Alexander reformed it, a levy of peasant farmers called to the colors for urgent situations. In less urgent situations, mercenaries were used and the national troops saved for dire emergencies.

The decline in the quality of the Macedonian army was paralleled by a decline in quantity. In 334 b. c. e. Alexander could raise 24,000 phalangites from Macedonia and 4,000 cavalry to take with him on campaign. By the time of the battle of Cynoscephalae (197 b. c. e.) Philip V could only raise 16,000 phalangites, 2,000 cavalry, and 2,000 mercenary peltasts from Macedon itself. Even this number required enrolling sixteen-year-olds and recalling retired veterans to national service. Philip attempted to reconstitute the manpower base of Macedonia by requiring families to produce children, forbidding the traditional practice of infanticide, and even resettling large numbers of Thracians in Macedonia proper. Twenty years later (171 b. c. e.), when Persus raised an army to resist the Romans, he could field 21,000 phalangites, 3,000 cavalry, and 5,000 peltasts. This was the largest army ever led by a Macedonian king since Alexander’s time.

The problems of quantity and quality of manpower worked to reinforce the Macedonian emphasis on infantry over cavalry. In the same manner that Napoleon adopted the column formation as a solution to controlling troops of poor quality with little training, so, too, the phalanx had the singular advantage of not requiring much training. As in the old hoplite phalanx, very little skill was required of the phalanx soldier, except that he hold his ground and move along with his comrades. While the phalangite also carried the sword to use in desperate situations, the degree of training in using this weapon was universally poor. In a fight with the Roman legionnaire, who used the sword as his primary weapon, the Macedonian soldier was a poor match.

The transformation of infantry in the Successor armies was paralleled by a transformation in the quality, numbers, and tactical use of cavalry. The same forces that worked to emphasize the importance of infantry worked to reduce the importance of cavalry on the battlefield. The Wars of the Successors destroyed any national spirit that remained after Alexander’s death, and the expense of cavalry led the Successors, especially the Macedonians, to recruit cavalry from the populace in much the same way as mercenaries were recruited. The monarch retained around his person a squadron or two of elite cavalry, but in terms of numbers and the ability to recruit and train cavalry, the cavalry forces of the Successors were but a pale copy of what they had been during Alexander’s time.

The tactical employment of cavalry changed as well, most strongly so in Macedonia. Wars in Macedonia were between phalanxes of heavy infantry, and the one thing cavalry could not do was successfully charge a disciplined line of spear infantry. The Macedonians reverted to the traditional uses of cavalry that were common during the hoplite era. Cavalry actions were now largely confined to the wings of the army with cavalry attacking cavalry, usually with no significant influence on the outcome of the battle. As it had been for centuries before, the defeat of the enemy’s cavalry again became an end in itself with little regard for how it affected the overall tempo or direction of battle. It became almost a tactical stereotype to open the battle with a cavalry attack rather than to wait until events unfolded and use the cavalry to exploit or create exploitable situations. This regression to cavalry tactics of the type found in the pre-Alexandrian era precluded the effective use of cavalry on the battlefield, and cavalry ceased to be the decisive arm it had been in the hands of Alexander. Cavalry doctrine remained static for more than two centuries, until the Parthians redesigned it entirely with the use of both the horse archers that defeated the Romans at Carrhae and the heavy cataphracti, armored knights that could break even the most disciplined body of infantry.

The Elephant’s Use in Western Warfare

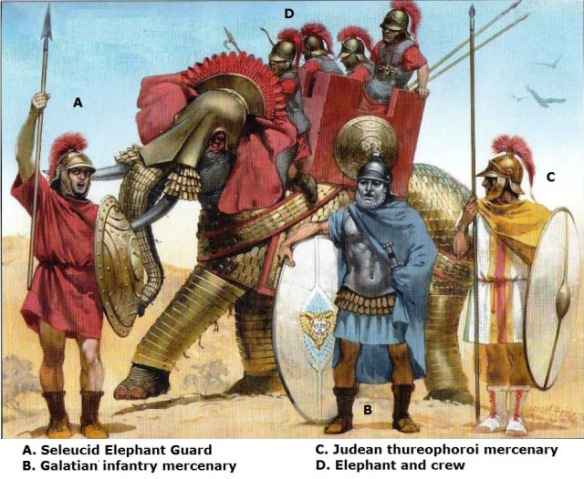

The Successors were, however, responsible for one significant innovation in the art of Western warfare: the use of the elephant. The time between Alexander’s death and the battle of Pydna (168 b. c. e.) was the only time in Western military history when the elephant played an important role in warfare. Alexander had first come in contact with the elephant at the battle of the Hydaspes and employed them in a small way in his own army. It fell to the Successors, particularly the Seleucids and Ptolemies, to acquire elephants in large numbers, and in a short time, every major power from Macedonia to Carthage had integrated them into their respective armies.

The most common use of the elephant was to screen the deployment and maneuver of cavalry and, on rare occasion, to lead attacks against infantry. Rarely were they used against fortified positions, and then almost always with failure. In concert with light infantry, elephants could be used to protect the flanks of the phalanx and, indeed, a new and important combat role for light troops was to distract and destroy enemy elephants. Given the expense and difficulty associated with acquiring, training, and employing elephants, these animals seem to have been among the most expensive and least effective instruments of ancient warfare, at least in the West. The last serious use of elephants by Western armies was at the battle of Magnesia (190 b. c. e.), and they failed to prevent the defeat of the Seleucids at the hands of Roman infantry.

FURTHER READING Adcock, F. E. The Greek and Macedonian Art of War. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957. Berthold, Richard M. “The Army and Alexander the Great’s Successors.” Strategy and Tactics 152 (June 1992): 45-47. Cambridge Ancient History. 14 vols. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1970. Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War within the Framework of Political History. Vol. 1, Antiquity. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975. Jouquet, Pierre. Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic World: Macedonian Imperialism and the Hellenization of the East. 2 vols. London: Ares, 1978. Seaton, Stuart. The Successors. London: Charnwood, 1987. Tarn, William W. Hellenistic Military and Naval Developments. London: Ares, 1975. —. Hellenistic Civilization. New York: Dutton, 1989.