It was on Tuesday 27 November 1095, while Doge Falier lay on his deathbed, that Pope Urban II called upon Western Christendom to march to the rescue of the East. The response was enthusiastic and widespread. By 1 December Count Raymond of Toulouse and many of his lords had declared themselves ready to take the Cross. From Normandy and Flanders, from Denmark, Spain and even Scotland, prince and peasant alike rallied to the call. In Italy too the general reaction was much the same; the people of Bologna actually received a letter from the Pope cautioning them against excess of zeal and reminding them not to leave without the consent of their priests – and, in the case of recently married men, of their wives as well. Further south Robert Guiscard’s son Bohemund, now Prince of Taranto, recognized the opportunity he had long been awaiting and raised a small army of his own. Pisa and Genoa, both rapidly gaining in importance as maritime powers, also scented new possibilities for themselves in the East and began to prepare their fleets.

But Venice hung back. Her own Eastern markets were already assured – particularly Egypt, which had become a major clearing-house for spices from India and the southern seas, providing in return a ready market for European timber and metal. Her people were too hard-headed to set much store by emotional outbursts about the salvation of Christendom; war was bad for trade, and the goodwill of the Arabs and the Seljuk Turks – who in the past quarter-century had overrun the greater part of Anatolia – was essential if the caravan routes to Central Asia were to be kept open. The new Doge, Vitale Michiel, preferred to wait, to judge for himself the scale of the enterprise and its prospects of success, before irrevocably committing the Republic. Not till 1097, when the first wave of Crusaders was already marching through Anatolia, did he even begin any serious preparations; and it was only in the late summer of 1099, after the Frankish armies had battered their way into Jerusalem, slaughtering every Muslim in the city and burning all the Jews alive in the main synagogue, that a Venetian fleet of 200 sail filed out through the Lido port.

In command was the Doge’s son, Giovanni Michiel, while the spiritual well-being of the expedition was entrusted to Enrico, Bishop of Castello and son of the former Doge Domenico Contarini. Down the Adriatic they went, calling in at the Dalmatian towns to pick up additional men and equipment, around the Peloponnese and so to Rhodes for the winter. There, according to one report, they received urgent representations from the Emperor Alexius, urging them to take no further part in the Crusade and to return home. Alexius had been horrified by the size of the Crusading armies. When he had first appealed to the Pope he had expected individual knights or small companies of trained mercenaries who would submit themselves to his authority and obey his orders; these voracious and utterly undisciplined hordes, some of them religious fanatics, others simple adventurers out for what they could get, had gone through his dominions like locusts and had totally destroyed that tenuous equilibrium of Christian and infidel on which the survival of his Empire now depended. Nor were they even confining their attacks to the Saracens: that same winter a Pisan fleet had actually been blockading the imperial port of Latakia while Bohemund – who had lost no time in carving out a principality for himself at Antioch – had attacked it simultaneously from the landward side. Considering the long history of Venetian-Byzantine friendship and the favoured treatment enjoyed by the Venetians throughout the Empire, Alexius can hardly have expected them to be guilty of similar conduct; by now, however, he was thoroughly disillusioned with the whole Crusade. If this was what was meant by a Christian alliance, he preferred to carry on alone. Meanwhile he had fought back hard at Latakia and the piratical Pisans had withdrawn, with ill grace, to Rhodes.

Thus, for the first time in their history, the Venetians and the Pisans found themselves face to face. The latter, despite their recent reverse, were in truculent mood; the former, who had watched Pisa’s rise to power with misgivings that increased with every passing year, had no intention of allowing these impudent upstarts a share in the rich spoils of the Levant. The battle that followed was long, and costly to both sides. In the end the Venetians made their point; with twenty Pisan ships taken, together with 4,000 prisoners – nearly all of whom were released shortly afterwards – they were able to extract an undertaking from their defeated rival to withdraw altogether from the eastern Mediterranean. Like all such undertakings made under temporary duress, however, it was soon forgotten; and that encounter off the Rhodian shore proved to be only the first round in Venice’s struggle with her commercial rivals which was ultimately to be measured not in years but in centuries.

There can be few clearer indications of the spirit in which Venice had embarked on the Crusade than the fact that, six months after her fleet had set out, it had still not struck a single blow for Christendom, nor indeed even reached the Holy Land. As always in her history, Venice put her own interests first; and even now, as winter turned to spring, those interests demanded a few more weeks’ delay for the greater glory of the Republic. Shortly before his departure, Bishop Enrico had visited his father’s church of S. Nicolò on the Lido and prayed that it might be given to him to bring back the body of its patron from Myra to Venice. Now the city of Myra, St Nicholas’s own bishopric and the place of his burial, stands on the mainland of Lycia almost opposite Rhodes. It had been largely destroyed by the Seljuk Turks, but the great church still stood – as indeed it still does – over the saint’s tomb. The Venetians landed, burst in and soon came upon three coffins of cypress wood. In the first two they found the remains of St Theodore and of St Nicholas’s uncle; the third, that of the saint himself, was empty. They interrogated the churchwardens, even subjecting them to physical violence in their determination to discover the whereabouts of the body; the unfortunate officials could only stammer that it was no longer in their possession, having been removed some years before by certain merchants from Bari. But the Bishop remained incredulous. Falling to his knees, he prayed loudly for the sacred hiding-place to be revealed. And, sure enough, just as the party was about to leave in disgust, a sudden fragrance in a remote corner of the church led them to another tomb. In it – so the story goes – lay the uncorrupted body of St Nicholas, clutching the palm, still fresh and green, that he had brought back from Jerusalem. All three corpses were triumphantly embarked and the ships, their mission accomplished, set sail at last for Palestine.

After the capture of Jerusalem in July 1099 the Crusading leaders had chosen as their sovereign Godfrey, Duke of Lower Lorraine. Refusing to wear a crown in the city where Christ had worn a crown of thorns, Godfrey had adopted the title of Defender of the Holy Sepulchre, and it was in this capacity that he received, in the middle of June 1100, a report that a large Venetian fleet had put in at Jaffa. The fighting was by no means over; much of the country still lay under Saracen occupation and Godfrey’s own naval resources were poor. He hastened down to the coast to welcome the new arrivals, but by the time he reached Jaffa he was far from well. As he had stopped off on his way to attend a banquet given in his honour by his vassal, the Saracen Emir of Caesarea, there were the inevitable rumours of poison. In fact the trouble is more likely to have been typhoid; but at all events Godfrey was barely able to receive the Venetian leaders before being forced to retire in a state of collapse to Jerusalem – leaving his cousin, Count Warner of Gray, to negotiate on his behalf.

The Venetians’ terms were hardly redolent of selfless Crusading zeal. In recognition of their assistance they asked free trading rights throughout the Frankish state, a church and a market in every Christian town and, in addition, a third of every other town that they might help to capture in the future. Finally, in return for an annual tribute, they demanded the entire city of Tripoli. Even if all this was granted, they undertook to remain in the Holy Land on this first visit for only two months, until 15 August.

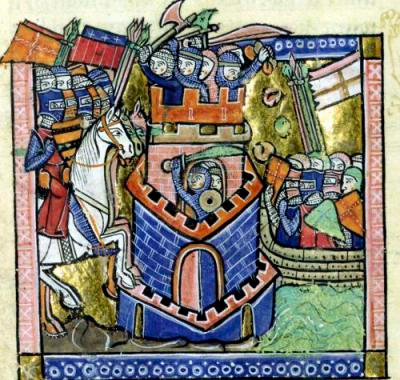

It was a hard, typically Venetian bargain; and the speed with which the Franks accepted it shows how desperate they were for naval support. It was agreed that the first objective should be Acre, and that Haifa should follow; unfortunately for Crusading plans, however, a strong north wind delayed the ships near Jaffa, and while they were still there the news reached them that Godfrey was dead. Here was a problem. The Frankish leaders were all anxious to be in Jerusalem during the disputes over the succession and the inheritances that were bound to ensue. On the other hand, there was now less than a month before the date fixed by the Venetians for their return; it was unthinkable not to make use of a fleet whose cooperation had been so dearly bought. Further discussions accordingly produced a compromise: the assault on Acre would be postponed; the immediate objective would be Haifa, nearer and less strongly fortified.

Although Haifa was defended by a small Egyptian garrison, the real force of its resistance came from the predominantly Jewish population who, remembering what had happened to their brethren in Jerusalem less than a year before, fought with a bitter determination to preserve their city. But the Venetian mangonels and siege machines were too much for them, and on 25 July – within a week of Godfrey’s death – they were obliged to surrender. Their fears proved to have been fully justified. A few managed to escape; the majority, Jews and Muslims alike, were struck down where they stood.

The Venetians themselves are unlikely to have played a leading part in the massacre. They were not a bloodthirsty people – merchants, not murderers. The Franks on the other hand had been guilty of this sort of thing before, not only in Jerusalem but in Galilee as well. The fact remains that this was a military alliance, and since Michiel, Contarini and their followers were present it is impossible to absolve the Venetians altogether from responsibility. Whether they themselves were conscious of it we cannot say; no mention of any atrocity occurs in the sketchy Venetian records. Nor is there any indication that they received the rewards guaranteed to them a month before, though they may have agreed to defer these until the political crisis was over. Soon after the fall of Haifa they set sail for home bearing with them, apart from the trophies and merchandise from the Holy Land, the saintly relics they had brought from Myra. On their arrival, which was neatly timed for St Nicholas’s Day, they received heroes’ welcomes from Doge, clergy and people, and the reputed body of the saint was reverently interred in Domenico Contarini’s church on the Lido.

Did the ceremony have a slightly hollow ring? It should have done, because the luckless churchwardens of Myra had told the truth. Thirteen years before the Venetians arrived there, a group of Apulian merchants had indeed removed St Nicholas’s body and had carried it back in triumph to Bari, where work had immediately begun on the basilica bearing his name – now one of the most superb romanesque churches in all Italy. Since the crypt of this glorious building had been consecrated as early as 1089 by Pope Urban himself, and since in the intervening years the great church must have been seen by countless Venetian sailors as it rose higher and ever higher above the city, it seems scarcely conceivable that the Doge and his advisers were unaware of the Bariot claims. As far as we know, however, they made no attempt to discredit them. We can only conclude that the whole thing was one gigantic exercise in self-deception; and that the Venetians, normally so levelheaded, were yet perfectly capable of persuading themselves that black was white when the honour and glory and profit – for the financial advantages from the pilgrim traffic were not to be despised – of the Republic demanded that they should. So far as they were concerned, the true corpse of St Nicholas lay in his tomb on the Lido. Several centuries were to pass before the claim was discreetly withdrawn.