The AH-1G Cobra, or “Snake” as it became known to Army aviators, carried 2.75-inch FFARs in either M158 7-tube or M200 19- tube rocket pods affixed to the wings. The chin-turret mounted the M134 7.62-mm minigun and M129 40-mm grenade launcher. Several air cavalry units armed Cobras with miniguns in M18/M18A1 gun pods installed on both wings, or the M35 armament subsystem, which included an M195 20-mm automatic cannon fixed to the left wing. On selected missions the Ah-1 carried the XM118 smoke grenade dispenser. All AH-1s mounted the M73 reflex sight for the pilot to fire the weapons systems. The Army equipped a limited number of Cobras with the CONFICS (Cobra Night Fire Control System) and the SMASH systems to provide the gunships with a night firing capability. A few early-model AH-1G/AH-1Q Cobras mounted either two M134 miniguns or two M129 grenade launchers in the turret, but problems with the ammunition feed systems caused the Army to abandon the twin-gun configurations.

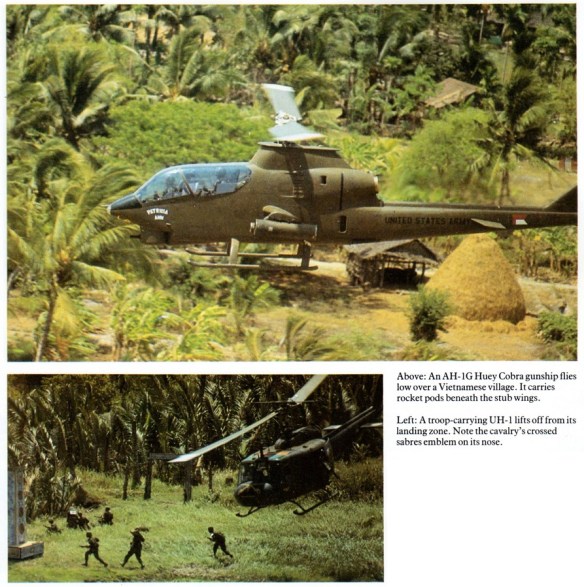

In late 1966 and early 1967 the AH-1G began to replace most of the gunships in air cavalry and aerial rocket artillery (ARA) units, providing more flexibility and firepower. Air cavalry troops (company) organized their helicopters into three platoons: the attack helicopters in the “Red” Aerial Weapon Platoon, the scouts in the “White” Aerial Scout Platoon, and the Hueys in the “Blue” Aerial Rifle Platoon. A combination of a scout and attack helicopters became “Pink” teams, and the Cobras, operating with scout helicopters, especially the OH-6, became one of the most effective combat multipliers in the U. S. Army. The scouts flew with their skids brushing the trees, and the attack helicopters dove in and blasted any enemy formations discovered. Many commanders in RVN estimated that their air cavalry units initiated as many as 90 percent of their engagements with the VC and NVA.

ARA units, in contrast to other gunships, operated under direction of artillery officers. Divisional or separate artillery commanders employed these helicopters to supplement conventional tube artillery. When called, ARA platoons communicated on fire direction radio frequencies, and the helicopter’s rockets were adjusted much like conventional artillery. ARA’s great advantage lay in its long-range and heavy firepower. ARA provided direct fire support to units out of range of conventional artillery. The Bell AH-1G Cobra carried up to seventy-six rockets, and with 17-pound warheads it delivered the same initial firepower as a battalion of 105-mm howitzers-devastating firepower for one helicopter.

The U. S. Marines also operated helicopter gunships in Vietnam and incorporated attack helicopters into their future tactical planning for both amphibious and vertical ship-to-shore operations. The Marines envisioned attack helicopters providing armed escort for troop-carrying helicopters; close-in-air support for beachheads and landing zones, including an antiarmor role; armed reconnaissance; and self-protection against armed enemy helicopters. In May 1968 the Marines ordered their own version of the Cobra. A preponderance of overwater flights by the USMC demanded a twin-engine AH-1, therefore Bell Helicopter, by this time a division of Textron, developed the AH-1J Sea Cobra. Constructed around the AH-1G airframe, the Sea Cobra included a twinpac of Pratt & Whitney T400 900-horsepower turboshafts, thus increasing available power. Bell also increased the AH-1J’s firepower by installing a three-barrel XM-197 20-mm cannon in a new nose turret. The Sea Cobra included improved dynamic components, avionics, and a rotor brake for shipboard operations.

While the USMC awaited the development and production of the first forty-nine AH-1Js, the Corps bought thirty-eight AH-1Gs from the Army. Army instructors conducted the initial training of Marine pilots, and, in April 1969, VMO-2 became the first operational Marine Cobra unit in Vietnam. In December the USMC transferred the AH-1Gs to HML-367. The same month flight evaluations began on the Sea Cobra, and the first AH-1Js entered service in February 1971, commencing combat operations the following month. Marine AH-1Js, including those of HMA-369, flew combat missions in Southeast Asia (SEA) until the final withdrawal of the United States in 1975. The USMC bought a total of sixty-seven AH-1Js, which remained the Marines’ primary attack helicopter for several years. The Corps transferred the AH-1Gs to reserve helicopter attack squadrons.

As early as 1966 the U. S. Army adapted a few UH-1Bs to carry up to six French-designed SS-11B wire-guided antitank missiles to engage hard targets. Adopted by the Army as the AGM-22B and mounted on the M-22 missile subsystem, the missiles were never a popular weapon. Gunners guided the SS-11 by eyesight, tracking the missile by a flare in its tail and adjusting the missile’s flight with a joystick. Wires, spooled out behind the missile, transmitted course corrections from the operator to the missile in flight. The system required highly trained gunners and a “fairly benign combat environment,” and, as both were in short supply, the accuracy of the AGM- 22 proved illusory at best (Williams 2003).

In 1966 the Army Aviation Test Board also armed two UH-1Bs with the new Hughes BGM-71 Tube-launched, Optically tracked, Wire-guided” (TOW) antitank missiles as part of the AH-56 Cheyenne test program, but the Hueys were placed in storage when funds were reduced for the AH-56. When the NVA began to introduce Soviet-manufactured tanks into RVN, the Army reactivated the TOW-equipped Hueys and conducted extensive firing tests before deploying the helicopters to Vietnam. Much more advanced than the AGM-22, the TOW provided far greater accuracy. The gunner simply maintained the sight on the target while the fire-control system guided the missile to the target. During the NVA “spring offensive” of 1972, Army pilots fired eighty-one TOW missiles and recorded fifty hits. In contrast, of the twenty-one SS-11 missiles fired during the same period, only three hit their targets.

AH-1 Cobras also destroyed several tanks during the siege of An Loc in 1972. Responding to a U. S. Army advisor’s request to support the ARVN troops against an overwhelming NVA attack, the Cobras dove through intense ground fire and destroyed three T-54s with 2.75-inch high explosive anti-tank (HEAT) rockets, halting the NVA attack. During the next few days, Army Cobras destroyed twenty T-54s with their rockets. Unfortunately, eight of the thirty-two Army aviators involved in the action died in combat. At an after-action review in the Pentagon, Air Force operational specialists claimed that the 2.75-inch rockets were not accurate enough to hit tanks. The Air Force contended that attack helicopters would never be a viable weapon on mid- to high-intensity battlefields. When asked how close the Cobra pilots fired their rockets, Lieutenant Colonel Bob Molonelli said, “About one hundred yards. You told us to kill them and we did.” The Air Force officers failed to account for the tenacity of Army aviators in their calculations. The success of TOW and rocket-firing helicopters in Vietnam substantiated the practicality of the antiarmor helicopter and inaugurated an intensive research program by the U. S. Army on how to best employ the versatile weapons systems (Williams 2003).

Lockheed Aircraft designed the AH-56A Cheyenne to meet U. S. Army requirements for the AAFSS, which began in 1964. On May 3, 1967, Lockheed rolled out the first of ten prototypes of the rigidrotor Cheyenne. A single General Electric T64-GE-16 3,435-horsepower turbine powered a four-bladed rigid main rotor and antitorque tailrotor, as well as a three-bladed pusher propeller mounted at the rear of the unusual aircraft. At 100 knots the aircraft’s stub wings assumed approximately 80 percent of the lift, allowing the Cheyenne to reach a top speed of 214 knots in level flight. Lockheed engineers provided armored, tandem seating for a pilot and copilot/gunner in a jet fighter-like cockpit and armed the Cheyenne with an innovative XM-112 swiveling gunner’s station, linked to a rotating belly turret containing an XM-52 30-mm automatic cannon and a chin turret with either an XM-51 40-mm grenade launcher or an XM-53 7.62-mm Gatling gun. An advanced-fire control computer, which included a laser range finder, controlled the guns as well as the eight TOWs and thirty-eight XM200 2.75-inch rockets carried in launchers mounted under the wings. Following the 1966 decision to buy the AH-1G, DoD decreased funding to the Cheyenne program. On August 9, 1972, because of delayed development, technological difficulties, rising costs, mishaps, and the appearance of two competitive helicopters developed by Bell and Sikorsky, DoD officially canceled the AH-56.

In 1970, with problems increasingly plaguing the AH-56 program, Sikorsky independently developed the S-67 Blackhawk attack helicopter prototype. Sikorsky’s intermediate AAFSS helicopter was an armed, modified version of the company’s proven S-61, H-3 Sea King. Two General Electric T58-GE-5 1,500-horsepower engines turned a five-bladed main rotor. New night vision systems provided targeting information to a Tactical Armament Turret (TAT-140) containing a 30-mm cannon; additional armament included up to eighteen 130-mm TOW missiles, and either 114 2.75-inch rockets or AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. Sikorsky engineers installed speed brakes on the trailing edges of the aircraft’s short wings to improve maneuverability and a retractable landing gear to increase speed. Although the aircraft set a number of new records during a rigorous test program from 1970 to 1974, the Army judged the Blackhawk unsatisfactory for its purposes. On December 14, 1970, the S-67 established a world speed record by flying at 249.53 knots over a 1.86-mile course. In 1974, near the end of the test program, Sikorsky replaced the conventional tailrotor with a ducted fan, allowing the S-67 to reach a speed of 264.7 knots in a dive. Unfortunately, in a demonstration roll during an air show at Farnborough, England, the S-67 struck the ground, destroying the aircraft and killing both pilots.

In 1971, Bell Helicopter introduced the model 309 King Cobra prototype, also company financed, to contend for the AAFSS contract. One of only two prototypes crashed, but the other flew in comparative trials with the Lockheed AH-56A Cheyenne and the Sikorsky S-67 Blackhawk. Army officials, however, determined that none of the aircraft met their requirements. A single Lycoming T55- L-7C 2,850-horsepower turboshaft powered the King Cobra. Bell designers equipped the King Cobra with a laser day and night sight, infrared fire control system, night vision TV, and armament similar to that of the Cheyenne and Blackhawk.

Kaman also entered the fray with an armed version of the Seasprite. The company modified six aircraft with a four-bladed tailrotor and tweaked the engines to raise the maximum gross weight to 12,500 pounds to offset the added armor plating. Kaman altered the nose section with a turret-mounted 7.62-mm minigun and installed two other miniguns to the sides of the aircraft. The modified Seasprite created no real interest, however, and Kaman dropped the project.

In the early 1970s the Army initiated the Improved Cobra Armament Program (ICAP), which resulted in the AH-1Q antiarmor version of the Cobra. The AH-1Q incorporated the XM65 TOW/Cobra missile subsystem. The XM-65 included a telescopic sight unit (TSU) mounted in the aircraft’s nose that magnified targets by thirteen times and allowed gunners to pinpoint their targets. The AH- 1Q carried up to eight Hughes BGM-71 130-mm TOW antitank missiles in paired, stacked launchers mounted on the outboard wing pylons. Depending on the mission, commanders had the option of installing either the M158 7-tubed or M200 19-tubed 2.75-inch FFAR rocket pods on the inboard pylons. In 1973 the Army deployed a modest number of AH-1Q Cobras to Vietnam, but the heat and humidity, resulting in high-density altitudes, prevented the aircraft from carrying full ammunition and fuel loads, initiating a search for a more powerful attack helicopter.

Bell Helicopter, Textron, produced another helicopter that saw extensive service in the RVN. In 1967 the U. S. Army, because of escalating prices for the OH-6 Cayuse and its spare parts, reopened bids for the LOH program. The Bell civilian Model 206A Jet Ranger, derived from the unsuccessful OH-4, won the competition the next year, which resulted in an order for 2,200 aircraft. Designated the OH-58A Kiowa by the Army, the helicopter had the usual Bell allmetal, two-bladed, semirigid main rotor system, but without the stabilizer bar, and a two-bladed “Delta-hinge” tailrotor. Powered by a single Allison 250-C10 T63-700 317-horsepower gas turbine engine, the Kiowa reached a maximum airspeed of 120 knots and carried a M-134 7.62-mm minigun in the air scout role. Designed as a single-pilot aircraft, the OH-58A could carry three passengers or 400 pounds of cargo to a range of 300 nautical miles and a service ceiling of 18,900 feet. The Navy evaluated the Jet Ranger as an ASW platform, ordering prototypes with folding blades and armed with an acoustic torpedo. The Navy rejected the ASW version but bought nearly 200 TH-57s for pilot training. Because of the high demand for helicopters during the Vietnam years, Bell signed a multiyear contract with Beech Aircraft to produce OH-58 fuselages and established production facilities in Canada, which manufactured most of the later OH-58/Jet Ranger models.

The helicopter received FAA commercial certification in October 1966, with civilian deliveries beginning in January 1967. Companies involved in offshore oil exploration demanded a helicopter capable of carrying more than the five passengers of the original 206A. In 1973, Bell engineers elongated the cabin of the 206 to accommodate seven passengers and designated the modification the Model 206L Long Ranger. Bell installed a spray rig for dusting crops in an agricultural version of the machine. Companies worldwide made use of the faster and more powerful 206L in sundry commercial applications, and thirty-five countries employed the military versions of the helicopter. In addition to the United States and Canada, the Jet Ranger was also manufactured in Australia and Italy.