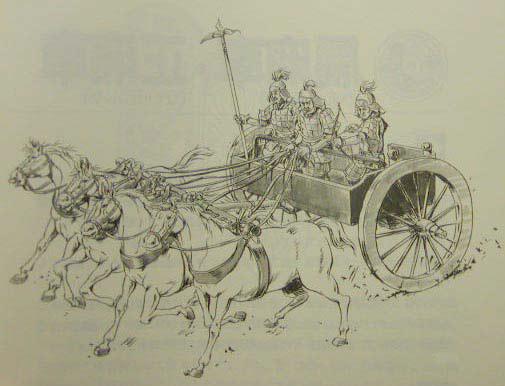

Despite a number of vehicles having been recovered from graves and sacrificial pits, all aspects of the chariot’s employment in the ancient period pose vexing questions, particularly whether they were deployed by themselves as discrete operational units or were accompanied by either loosely or closely integrated infantry. Because even the oracular inscriptions for King Wu Ting’s well-documented reign provide few clues, and the tomb paintings recently discovered that date to the Warring States and thereafter mainly depict hunting scenes and parades, far more is known about the chariot’s physical structure than its utilization. The chariot’s essence has always been mobility, but prestige and displays of conspicuous authority rather than battlefield exploitation may have been defining factors in the Shang.

Some traditionally oriented scholars continue to assert that chariots played a significant role in Shang warfare; others deny that they were ever employed as a combat element. The Shang’s reputed employment of chariots, whether nine or seventy, to vanquish the Hsia is highly improbable given the complete absence of late seventeenth-century BCE or Erh-li-kang artifacts that might support such claims. However, Warring States writers idealistically ascribed differences in conception and operational characteristics to the Three Dynasties: “The war chariots of the Hsia rulers were called “hooked chariots,” because they put uprightness first; those of the Shang were called “chariots of the new moon,” because they put speed first; and those of the Chou were called “the source of weapons,” because they put excellence first.”

The few figures preserved in Shang dynasty oracular inscriptions, Chou bronze inscriptions, and other comparatively reliable written vestiges indicate that chariots were sparsely employed in Shang and Western Chou martial efforts. The chariot’s first recorded participation in Chinese warfare actually occurs about seven to eight hundred years after their initial utilization in the West, ironically just before the Near Eastern states would abandon them as their primary fighting component due to infantry challenges. King Wu Ting’s use of a hundred vehicle regiments for expeditionary actions, already discussed, seems to have initiated their operational deployment, though the only concrete reference to Shang chariots (ch’e) appears in the quasi-military context of the hunt.

Chariots must have been extensively employed in the late Jen-fang campaigns, but no numbers have been preserved. Thus the next semi-reliable figure is the universally acknowledged 300 chariots that were employed by King Wu of the Chou to penetrate the Shang’s massive troop deployment at the Battle of Mu-yeh, precipitating their collapse. Some accounts suggest that the Chou had another 50 chariots in reserve, while the number fielded by the Shang, strangely unspecified in the traditional histories, could hardly have been less than several hundred. King Wu reportedly had a thousand at his ascension, some no doubt captured from the Shang, though others may have belonged to his allies and merely been numbered among those present for the ceremony. Several hundred were also captured from the Shang’s allies in postconquest campaigns, as well as in suppressing the subsequent revolt.

Nevertheless, chariots seem to have been minimal in early Western Chou operational forces. Scattered evidence suggests that field contingents never exceeded several hundred, with as few as a hundred chariots participating in expeditionary campaigns. Although one of their efforts against the Hsien-yün resulted in the capture of 127 chariots from a supposedly “barbarian” or steppe power, King Li’s campaign against the Marquis of E seems to have been typical. Despite total enemy casualties being nearly 18,000, inscriptions on the bronze vessel known as the Hsiao-yü Ting indicate that a mere 30 chariots were captured in one clash, though a second force of 100 is also mentioned. Somewhat larger numbers were deployed slightly later in campaigns against the Wei-fang, but the maximum figure ever reported for the Western Chou, the 3,000 supposedly dispatched southward against the rising power of Ching/Ch’u in King Hsüan’s reign (827-782), is certainly exaggerated despite the king’s reputation for having revitalized Chou military affairs, as well as unreliable because it is based solely on an ode known as “Gathering Millet.”

The chariot’s effectiveness in the Shang, early Chou, and perhaps even beyond must be questioned in the face of the constraints discussed below, the difficulties that will be examined in the next section, and the lessons that can be learned from contemporary experiments with replica vehicles. However, it should be remembered that although numerous reasons can be adduced why chariots could not have functioned as generally imagined, voluminous historical literature, both Western and Asian, energetically speaks about their employment in battle. Ruling groups were still expending vast sums to build, maintain, and employ chariot forces in the Warring States period, and the Han continued to field enormous numbers against steppe enemies, incontrovertible evidence that rather than being historical chimeras or simply artifacts of military conservatism, they continued to be regarded as crucial weapons systems.

Although all the Warring States military writings contain a few brief observations on chariot operations, only two, the Wu-tzu and Liu-t’ao, preserve significant passages. Primarily important for understanding the nature of the era’s conflict, they still furnish vital clues to the chariot’s modes of employment and identify a number of inherent limitations that would have inescapably plagued the Shang and Western Chou, long before chariots would explosively multiply to become the operational focus for field forces.

Chariots were considered one of the army’s core elements: “Horses, oxen, chariots, weapons, relaxation, and an adequate diet are the army’s strength. Fast chariots, fleet infantrymen, bows and arrows, and a strong defense are what is meant by ‘augmenting the army.’” Several passages indicate that chariots were viewed as capable of “penetrating enemy formations and defeating strong enemies.” Those used in conjunction with large numbers of attached infantry and long weapons were said not only to be able to “penetrate solid formations” but also to “defeat infantry and cavalry.” “When the horses and chariots are sturdy and the armor and weapons advantageous, even a light force can penetrate deeply.” “Chariots are the feathers and wings of the army, the means to penetrate solid formations, press strong enemies, and cut off their flight.” Before the advent of cavalry, they also acted as “fleet observers, the means to pursue defeated armies, sever supply lines, and strike roving forces.”

Passages in Sun Pin’s Military Methods and other works indicate that somewhat specialized chariots evolved in the Warring States, the basic distinction being between faster (or lighter) models and heavier chariots protected by leather armor and designed for assaults. A few of even greater size and dedicated function were thought capable of accomplishing even more: “If the advance of the Three Armies is stopped, then there are the ‘Martial Assault Great Fu-hsü Chariots.’” “Great Fu-hsü Attack Chariots that carry Praying Mantis Martial warriors can attack both horizontal and vertical formations.” Variants with a smaller turning ratio, known as “Short-axle, Quick turning Spear and Halberd Fu-hsü Chariots,” might be successfully employed “to defeat both infantry and cavalry” and “urgently press the attack against invaders and intercept their flight.”

Chariots were deemed astonishingly powerful: “Chariots and cavalry are the army’s martial weapons. Ten chariots can defeat a thousand men, a hundred chariots can defeat ten thousand men.” The Liu-t’ao’s authors even ventured detailed estimates of the relative effectiveness of chariots and infantry: “After the masses of the Three Armies have been arrayed opposite the enemy, when fighting on easy terrain one chariot is equivalent to eighty infantrymen and eighty infantrymen are equivalent to one chariot. On difficult terrain one chariot is equivalent to forty infantrymen and forty infantrymen are equivalent to one chariot.”

These are startling numbers, all the more so for having been penned late in the Warring States period when states still numbered their chariots by the thousands. Even allowing for exaggeration, given that the Liu-t’ao generally reflects well-pondered experience and is a veritable compendium of Warring States military science, the era’s commanders must have had great confidence in the chariot’s capabilities. Nevertheless, it might be noted that the great T’ang dynasty commander Li Ching, upon examining these materials in the light of his own experience at a remove of a thousand years, concluded that the infantry / chariot equivalence should only be three to one.

Chariots were also employed to ensure a measured advance in the Spring and Autumn, Warring States, and later periods when they no longer functioned as the decisive means for penetration. Li Ching’s comments about his historically well-known expeditionary campaign against the Turks indicate that even in the T’ang and early Sung they were still considered the means to constrain large force movements: “When I conducted the punitive campaign against the T’u-ch’üeh we traveled westward several thousand li. Narrow chariots and deer-horn chariots are essential to the army. They allow controlling the expenditure of energy, provide a defense to the fore, and constrain the regiments and squads of five.”

Although certainly not applicable to the Shang, chariots could also be cobbled together to provide a temporary defense, particularly the larger versions equipped with protective roofs. The authors of the great Sung dynasty military compendium, the Wu-ching Tsung-yao, after (somewhat surprisingly) commenting that “the essentials of employing chariots are all found in the ancient military methods,” concluded that “the methods for chariot warfare can trample fervency, create strong formations, and thwart mobile attacks. When in motion vehicles can transport provisions and armaments, when halted can be circled to create encampment defenses.”

Numerous examples of employing chariots as obstacles or for exigent defense are seen as early as the Spring and Autumn period. The later military writings cite several Han dynasty exploitations of “circled wagons” being employed as temporary bastions, including three incidents in which beleaguered commanders expeditiously deployed their chariots much as Jan Ziska would in the West to successfully withstand significantly superior forces. Sometimes the wheels were removed, but generally the chariots were simply maneuvered into a condensed array.