The offensive in the Levant, commanded by Shahrvaraz, was matched by the campaigns of Shahin in Asia Minor, which was overrun from the east for the first time since the incursions of Shapur I in the mid-third century. The old inner frontier which stretched from Trapezus through Satala to Melitene was already in Persian hands, and Anatolia could be raided virtually at will. In 615 a Sassanian force under the command of the general Shahin reached Chalcedon, across the waters of the Bosporus from Constantinople. When a desperate plea for peace was brought to Khusro by a high-level legation during the following winter, the ambassadors were simply interned and later put to death (Chron. Pasch. 615). In 617 Persian seaborne forces occupied Cyprus. It appears that most of the overland assaults on Asia Minor were directed, as might be expected, along the Roman road network north of the Taurus, while Roman resistance concentrated in the mountainous regions of the south. As the imperial mints in Cyzicus and Nicomedia ceased production in 616 and 619 respectively, Heraclius struck coins in Seleucian Isauria in 616-17 and in the fastness of Isaura itself in 618. Persian attention turned, as might be expected, to the richest cities, and Ancyra, Sardis, and Ephesus were sacked and plundered. While the immediate impact of warfare was dramatic, and is illustrated by archaeological evidence from these cities, it is less clear that the Sassanians, in the space of less than ten years, could have brought to an end the urban culture of late Roman Asia Minor. A broad study of the impact of the Persians throughout the territories that they conquered in the Roman Near East argues that we should distinguish between the brutality and the devastation that they inflicted on centers of Roman resistance, and the much lighter touch with which compliant local populations were handled.

Roman fortunes reached their lowest ebb in 622. A full-scale Sassanian attack coincided, surely by design, with an onslaught from the Balkans by the Avars. Heraclius, who had taken the field against the Persian army, returned in haste to Constantinople to begin negotiations with the Avars, who may have besieged Thessalonica during this period. In 623 the emperor ventured beyond the protection of the Thracian long walls to seal an agreement with the Avar Chagan, but was almost captured in an ambush, losing much of his entourage. In the crisis one of the emblems of the city’s protection, the robe of the Virgin which was kept at the church at Blachernae, outside the Theodosian Walls, was hurried for safe-keeping to St Sophia. Humiliating terms had to be agreed with the Avars. Ancyra, the greatest fortress of central Anatolia, was probably captured in 622. In 623, doubtless exploiting the opportunity provided by their new base in Egypt, the Sassanians seized the island of Rhodes and deported many of its inhabitants. Their hands were at the empire’s throat.

Events were subject to an extraordinary reversal between 624 and 630.31 Heraclius assembled a field army at Caesarea in Cappadocia, and then marched through northeast Asia Minor into Azerbaijan, through the regions with largely Christian populations which had been under Roman control after 591. Khusro’s army, which had mustered at Ganzak, the location of Bahram’s defeat in 591, withdrew across the Zagros. Heraclius chose to attack and destroy the fire-temple at Takht-e Suleiman, a formidable fortress which was the symbolic center of Sassanian power in the northwest of the empire, and overwintered with his forces in the valley of the river Kur in Albania. In the following campaigning season he maintained the Roman presence along the southern side of the Caucasus and occupied winter quarters near Lake Van. The Persian riposte came in 626. The two Sassanian generals Shahrvaraz and Shahin led a major counteroffensive, with Shahin advancing through Armenia and Shahrvaraz through the Cilician Gates, both aiming for Constantinople. The plan was coordinated with the Avars, and the Khagan simultaneously led an enormous force against Constantinople from the West. Heraclius blunted the Persian effort by defeating Shahin’s forces in Anatolia, and Roman naval forces proved strong enough to prevent Shahrvaraz, who was again encamped at Chalcedon, from crossing the sea of Marmara and joining forces with the Khagan. The Avars, aided by the Slavs, beleaguered Constantinople from the Thracian side in huge numbers through late July and early August 626. The defenders, facing personal annihilation and fighting for the survival of the Roman Empire, forged an unprecedented unity in face of the peril. The icon of their salvation was the robe of the Virgin of Blachernae, and the accounts of the siege raised the cult of the Virgin Mary, and the myth of her protective powers, to an unprecedented prominence. The fullest account of the siege, in the Chronicon Paschale, begins with an explicit acknowledgment of the Virgin’s role:

It is good to describe how now too the sole most merciful and compassionate God, by the welcome intercession of the undefiled Mother, who is in truth our Lady Mother of God and ever-Virgin Mary, with his mighty hand saved this humble city of his from the utterly godless enemies who encircled it in concert, and redeemed the people who were present within it from the imminent sword, captivity, and most bitter servitude. (Chron. Pasch. 626)

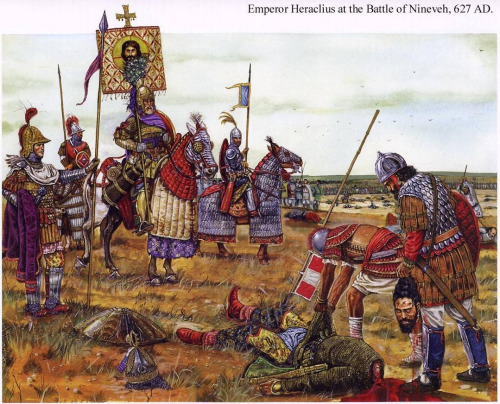

Heraclius participated in the thanksgivings at the capital over the winter of 626 before returning to the offensive in 627. He too made common cause with an ally from the steppes, the western Turkic Khagan, and advanced through Lazica and Iberia to meet these new allies outside the city of Tiflis, which was placed under siege. While the Turks maintained the blockade, the Romans moved south again into Azerbaijan. In December they crossed the Zagros and confronted a large Sassanian army near Nineveh. Heraclius’ victory opened the path for the Romans to advance south on Ctesiphon itself. The presence of a victorious and threatening enemy force on the river Zab achieved precisely the same effect as Bahram’s mutiny had done in 591. The Sassanian king Khusro II was overthrown and murdered, to be replaced by his son Kavad Siroe who negotiated an armistice and sued for peace. Heraclius returned to Constantinople and a new treaty was struck with the Persians which restored the boundary between the two empires along the frontier which had prevailed before 591, running from Lazica through Theodosiopolis and Citharizon to Dara in Mesopotamia.

Complications followed. Kavad Shiroe himself died in autumn 628 and was succeeded by his young son Ardashir. Meanwhile, most of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt remained in Sassanian hands under the control of Shahrvaraz, who was now based in Alexandria. He entered into negotiations with Heraclius to restore the Near East to Rome, provided that Rome supported his own bid to take power at Ctesiphon. He demanded that the northern frontier section of the empire should now also be shifted westwards to the line of the upper Euphrates. Heraclius, however, achieved a crucial prize, the restitution of the True Cross to Jerusalem. At the beginning of 630 Shahrvaraz entered Ctesiphon, and had Ardashir killed in April. Six weeks later he himself was dead and was succeeded in power by a daughter of Khusro II, who was forced by Heraclius to restore to Rome the Transcaucasian territory occupied between 591 and 602.

The Persian state now imploded into a civil war which saw six short-lived rulers succeed to the throne until the accession of Yazdgird III, the last Sassanian king who ruled between 633 and 651. Heraclius meanwhile celebrated his triumph by becoming the first Roman emperor to enter Jerusalem, where he presided over the ceremony of the restoration of the Cross.

Heraclius’ success in the last great war with the Persian Empire depended on the Roman ability to transform the nature of their empire at a moment when it was on the verge of disintegration. This transformation took many forms. Heraclius’ own route to power, from Africa via Alexandria to Constantinople, which took two years and involved the organization of the resources of Egypt and the Near East against the usurper Phocas, prepared the ground for a new style of rulership. Heraclius himself broke with a tradition more than two centuries old by opting to lead Roman forces on campaign in person. Just as his coup had illustrated the old secret of empire, that emperors might be created elsewhere than at the capital, so his brash campaigning showed that, in moments of extreme crisis, aggression in other critical areas paid greater dividends than relying on survival in fortress Constantinople. His personal style of leadership was linked to strategic adaptability. The emphasis on a cavalry strike force, which had been the hallmark of Roman armies since the fourth century, was reversed. Heraclius’ wars were fought by troops in which infantry predominated, as was to be the case with later Byzantine forces. One reason for this may simply have been that it was less expensive and logistically less challenging to maintain infantry armies in the field.

Heraclius and his regime kept their nerve and drew on long experience during the years of crisis. Apart from maintaining a tactical and strategic initiative during the campaigns, they also played their diplomatic cards to good effect. The defense of the Balkans had to be abandoned. The Avars were held in check by tribute payments between 604 and 619, although they controlled all Illyricum west of Serdica and Naissus, which were both sacked around 614. The Sclaveni, whose diffused leadership was less amenable to diplomacy, were a continuous threat in Macedonia, Thessaly, and Greece. Thessalonica survived onslaughts in 604, 615, and 618 thanks to its mighty fortifications, stout local resistance, and the protection of St Demetrius. The Slavs created a primitive fleet of boats made from hollow tree trunks, with which they menaced the Aegean islands and the west coast of Asia Minor, and which almost succeeded in creating a bridge between the Persian and Avar forces at the siege of Constantinople in 626. After this failure the Avar-Slav coalition appears to have fractured, and although Slav colonization of the Balkans continued apace, the power of the Khagan ebbed away. Meanwhile on the eastern front, Rome struck critical new alliances with the Turkic tribes, who were now the most powerful force on the steppes. They were soon to show themselves to be a greater danger to the Sassanians than the Hephthalites had been in the fifth century.