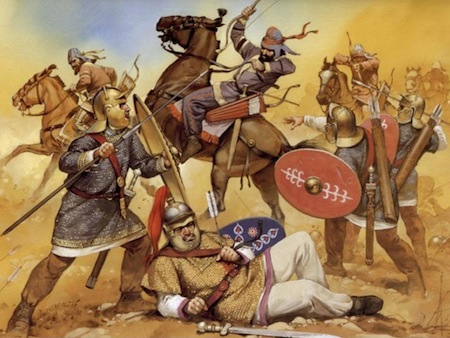

The Battle of Carrhae between the Parthian Empire and the Roman Republic in 53 BC. The Parthian Surena decisively defeated a Roman invasion force, led by Marcus Licinius Crassus. It was one of the most crushing defeats in Roman military history.

Parthian Commander – The Legendary General Surena. Commander Surena and Arsacid Parthian Army L – R: Parthian Cataphract, Commander General Surena, Mitra Standard Bearer. Surena the Legend

In the ancient world, Parthia was a country situated in what is now northern Iran. Its relations with Rome had been cordial until 65. There was no cause for war 10 years later when Crassus (115-53) set off from Rome with a large army; Crassus desired the glory and bounty of a victorious campaign; he was disappointed. In 54, he crossed the Euphrates River and began to invade Parthia, but his soldiers were not experienced in desert warfare. They were surrounded in heavy dust by Parthian horsemen and archers who decimated the Roman legions. Crassus was slain while trying to escape from Carrhae.

Seventeen years later, Mark Antony (83?-30) resumed the war, attempting to invade Parthia over the Armenian mountains, but the Armenian king refused to help, and Parthian horsemen raided Mark Antony’s supply train and destroyed his siege guns. His attempt to seize the fortress of Praspa failed, and the Romans were forced to retreat with severe losses.

Ventidius, when at war with the Parthians, did not lead his men out until the Parthians were less than half a mile away. Then he made a sudden advance and came so close to them that by meeting them face to face he avoided the arrows, which they usually fired from a distance. Therefore by this stratagem, because he made some show of confidence, he rapidly defeated the barbarians. Publius Ventidius (consul 43 BC) had served with Caesar and later supported M. Antonius. He was sent to recover Asia and Syria from the Parthians and in 39 and 38 BC won three distinguished victories.

When Marcus Antonius was fighting the Parthians, who were bombarding his army with an enormous number of arrows, he ordered his men to crouch down and form a tortoise (testudo). The arrows passed over this without harming the soldiers and the enemy was soon exhausted.

CILICIAN GATES (39) – Parthian War

After Philippi, Antony proceeded eastwards with the intention of waging a war against the Parthians. He sent Publius Ventidius ahead to pave the way. On the way Ventidius encountered Quintus Labienus, who had fought with Brutus and Cassius on the losing side and had not dared to return home for fear of the consequences. Labienus had not yet received some Parthian troops that he was expecting, and he was so terrified of Ventidius that he ran away through Syria with Ventidius on his heels. Ventidius overtook him near the Cilician Gates [Giilek Bogazi]. It was here that the expected Parthian troops caught up with Labienus, but at the same time Ventidius received a reinforcement of heavy-armed infantry. Ventidius remained judiciously encamped on the heights for fear of the Parthian cavalry. They, on the other hand, were utterly fearless and self-confident. They did not even wait to join Labienus but approached the heights and charged straight up them. The Romans on top had little difficulty in hurling them back down the hill, killing many of them. Even more were killed by their own people when those fleeing downhill charged into others who were still ascending. The survivors fled into Cilicia. Labienus himself offered no opposition but attempted to escape after dark. His plan became known to Ventidius, who set ambushes and either killed his men or won them over to his own side, but Labienus managed to get away. He was later found and killed. Plutarch, Antony, 33(4); Dio Cassius, 48: 39-40

AMANUS M (39) – Parthian War

After recovering Cilicia, Ventidius proceeded to Mount Amanus [Nur Daglari], having first sent Pompaedius Silo ahead with the cavalry. Pompaedius tried to occupy the exceedingly narrow Amanic Gates but he was defeated by Phranapates, who was in charge of the Parthian garrison at the pass. Pompaedius would have lost his life if Ventidius had not happened to arrive at that time and fallen unexpectedly upon the enemy. With his superior numbers he killed many of them, including Phranapates. Dio Cassius, 48: 41(1-4); Plutarch, Antony, 33(4); Strabo, 16: 2, 8

GINDARUS (38) – Parthian War

Publius Ventidius heard that Pacorus, the son of Orodes of Parthia, was preparing to invade Syria. This worried him because his troops were still in winter quarters and nothing was in place for a reception. He resorted to subterfuge by getting a friendly ‘confidence’ to the ears of Pacorus to the effect that his men would do better to cross the Euphrates at their customary place rather than further down where the river ran through a plain. Pacorus was deceived by what he assumed was deliberate misinformation and he crossed the river lower down, as Ventidius had intended. This route was the longer of the two, which gave the Romans more time to prepare. They allowed the Parthians to cross the river without opposition and were conspicuous by their absence on the far side. Consequently, when the Parthians reached the Roman camp at Gindarus, they attacked it immediately, expecting to take it with ease. A sudden sally took them by surprise, and as the camp was on high ground they were easily defeated by the heavy-armed Roman soldiers charging down on them. When Pacorus was killed, the Parthians gave up the struggle and were either killed or fled. The battle came to be regarded as settlement in full for the disaster at Carrhae (53) and the death of Crassus, which had been such a bitter humiliation to the Romans. Plutarch, Antony, 34(1); Dio Cassius, 49: 19- 20(3); Strabo, 16: 2, 8

PHRAASPA (36) – Parthian War

The successful campaign of Publius Ventidius in Parthia (Cilician Gates, 39, et seq.) might have aroused some feelings of jealousy in Mark Antony. In consequence, Ventidius diplomatically postponed further activities as a precaution. Antony eventually set out for Parthia himself two years later, after Phraates had killed his own father and seized the kingdom. He received reinforcements from Artavasdes of Armenia, which brought his forces up to 60,000 Romans with 10,000 cavalry and 30,000 other nationals. Winter was approaching but Antony was impatient. Antony marched on from Armenia through Atropatene in such a hurry that he refused to wait for his 300 wagons of siege-engines, which were to follow behind in the care of a large force under Oppius Statianus. When Phraates heard about this, he sent a strong force of cavalry which surrounded Statianus, killing 10,000 of his men and destroying the siege equipment. Meanwhile Antony was besieging Phraaspa [Takhti Suleiman], the royal city of Media, and was bitterly regretting his folly over the engines. When the Parthian army arrived, Antony tried to draw them off to a pitched battle by making an expedition with 10 legions and all his cavalry. The Parthians started to encircle his camp and so Antony pretended to be in retreat. He marched his men in perfect formation past the barbarian lines but had given instructions for a charge as soon as the legions were within attacking range. The barbarians repelled the initial cavalry charge, but their horses were terrified and bolted when the legions followed up the attack, creating as much noise as they could. The Roman cavalry pursued them for many miles but, at the end of the day, the enemy losses were estimated to have been a mere 80 killed and 30 taken prisoner. On their way back to Phraaspa, the Romans were again attacked and managed to reach their camp only with great difficulty. The siege of Phraaspa had to be abandoned. Plutarch, Antony, 38-39; Dio Cassius, 49: 25- 26(2)