To the astonishment of many, high-seas piracy, a crime thought long relegated to legend, made headlines in late 2005 when a luxury cruise ship was attacked off the Somali coast. The Seabourn Spirit, carrying 151 Western tourists, managed to evade capture but not without one of its security officers wounded and the ship itself damaged by rocket-propelled grenades. It was a miracle that the ship escaped; since March, 28 vessels had been attacked in the same waters, many of which were hijacked.

In 2005 modern-day piracy was as violent, as costly, and as tragic as it ever had been in the days of yore. Pirates no longer fit the Hollywood image of plundering buccaneers—with eye patches, parrots on their shoulders, cutlasses in their teeth, and wooden legs—but were often ruthless gangs of agile seagoing robbers who attacked ships with assault rifles and antitank missiles. According to the International Maritime Bureau, the organization that investigates maritime fraud and piracy, there had been 325 reported attacks on shipping by pirates worldwide the year before, in 2004. These statistics, the IMB said, reflected only reported incidents directed at commercial shipping and represented a fraction of the actual number. Most acts of piracy went unreported because shipowners did not want to tie up a vessel, costing tens of thousands of dollars a day to operate, for lengthy investigations. The human cost was also high—399 crew members and passengers were killed, were injured, were held hostage, or remained missing at the end of 2004. These statistics did not include, however, those innocent passengers, tourists, commercial fishermen, or yachtsmen whose mysterious disappearances were unofficially attributed to acts of piracy or maritime terrorism.

PIRACY ANCIENT AND MODERN

Piracy, a crime as old as mankind, has occurred since the earliest hunter-gatherer floated down some wilderness river on a log raft and was robbed of his prized piece of meat. Homer first recorded in The Odyssey an act of piracy around 1000 BCE. In many parts of the world, the culture of piracy dates back generations; ransacking passing ships was considered part of local tradition and an acceptable though illegal way of earning a living.

In the modern age, pirates found it relatively easy to attack a ship and make a clean getaway. Sea robbers on small, fast boats could quickly approach the rear of a ship within the blind spot of its radar, toss grappling hooks onto the rail, scale the transom, overpower the crew, and loot the ship’s safe. In less than 20 minutes, raiders would be back in their boats, often tens of thousands of dollars richer. Only a few pirates were ever caught, making it clear that plundering a ship was far less risky than robbing a bank.

Historical events and technological innovation also conspired to make modern piracy much easier to commit. Following the end of the Cold War, superpower navies ceased to patrol vital waterways, and local nations were left to deal with problems that heretofore had been international in nature. Pirates no longer had to rely on cotton sails, oars, sextants, and dead reckoning to mount an attack. Modern-day pirates used mobile phones, portable satellite navigation systems, handheld VHF ship-to-ship/shore radios, and mass-produced fibreglass and inflatable dinghies that could accommodate larger and faster inexpensive Japanese outboard motors. Indeed, the pirates who attacked the Seabourn Spirit had taken a page from Blackbeard and had launched their attack from a mothership stationed far offshore.

PIRACY FOR GAIN OR TERROR

Several types of piracy existed in 2005. The most common one was the random attack on a passing ship—a mugging at sea. Merchant vessels were slow-moving, lumbering beasts of trade that paraded in a line down narrow shipping lanes. They presented easy targets. The booty for these pirates was crew members’ possessions—watches and MP3 players—as well as the cash aboard the ship. A second type of attack was one planned in advance against vessels known to be carrying tens of thousands of dollars in crew payoff and agent fees. With the complicity and connivance of local officials, transnational crime syndicates employed pirates to pillage these vulnerable ships.

Though little known outside the maritime industry, crime syndicates also organized the hijackings of entire ships and cargo. With military precision, a ship carrying cargo that could easily be sold on the black market would be taken over, and it would simply disappear from the face of the Earth; the bodies of the crew would often be found washed up on a deserted shore some days later. The stolen vessel would become a phantom ship, with a new name, new home port, new paint job, and false registration under a different national flag. The vessel would be used to transport drugs, arms, or illegal immigrants or utilized in cargo scams.

Modern piracy took another, even more ominous turn. Pirates discovered that kidnapping the master and another officer was more lucrative than merely stealing the captain’s Rolex watch. In 2004 a record 86 seafarers were kidnapped, and in nearly every case a ransom was paid.

There is a long-standing link between piracy and terrorism, and the possibility of terrorism at sea became a growing concern post-September 11, 2001. Maritime terrorism was not new, however. In 1985, members of the Palestine Liberation Front attacked an Italian cruise ship, the Achille Lauro, and one of the passengers was shot and thrown overboard; in 2001 Basque separatists attempted to bomb the Val de Loire on a passage between Spain and the United Kingdom; and in February 2004 Abu Sayyaf, a terrorist group associated with al-Qaeda, admitted having planted explosives that sank SuperFerry 14 in Manila Bay. Of the 900 persons aboard that ferry, 116 lost their lives.

DEFENSE

Merchant ships in 2005 had no real defenses against an attack. Fire hoses might blast outboard, decks could be well lighted, and an extra crew member with a handheld radio might patrol the decks, but these precautions were not adequate. They merely indicated to pirates lying in wait that a ship was aware that it had entered pirate territory and that another ship in the vicinity without these obvious defenses might present a softer target. The Seabourn Spirit had been a little better equipped than most. She repelled the pirates by use of firehoses as well as a nonlethal acoustic weapon that aimed an earsplitting noise at the attackers; one of the passengers said the pirates fled because they thought the ship was returning fire.

Even the most modern and sophisticated vessel was vulnerable to attack. Suicide bombers in October 2000 had nearly sunk the U.S. destroyer Cole, a state-of-the-art warship, and in 2002 suicide terrorists had attacked the modern supertanker M/V Limburg, laden with Persian Gulf crude oil in the Gulf of Aden.

PIRACY IN THE MALACCA STRAIT

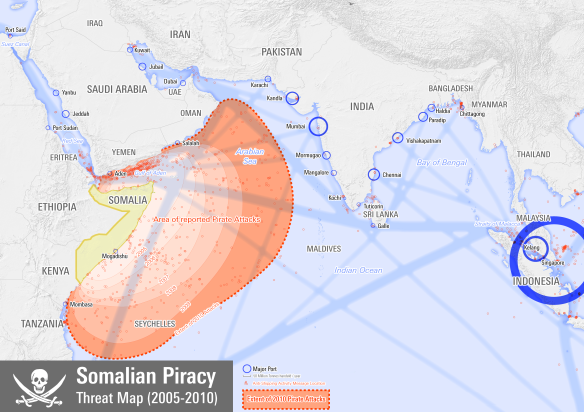

In 2005 maritime officials were concerned that terrorists might target the world’s strategic maritime passages, blocking the movement of global trade. Attention focused on the Malacca Strait, the gateway to Asia, conduit of a third of world commerce, and a prime hunting ground for pirates. About 80 percent of the oil bound for Japan and South Korea was shipped from the Persian Gulf through the strait. In addition, some 50,000 ships transited this narrow channel annually. U.S. officials expressed fears that one day terrorists trained to be pirates—as terrorists trained to be pilots for the September 11 attacks—would take over a high-profile ship and turn it into a floating bomb and close the strait. Disrupting the flow of half the world’s supply of oil that is transported through the passage would have a catastrophic effect on the world economy.

Though the U.S. government offered Malaysia and Indonesia (nations through which the strait passes) military patrol boats and personnel to guard the waterway, the offer was quickly rejected by both littoral states on the grounds that the patrolling of their waters by American forces was a violation of territorial sovereignty. Those nations were also mindful that an American military presence in the strait would stir an already restive Muslim population within their countries. By 2005 Malaysia and Indonesia together with the city-state of Singapore, located at the mouth of the strait, had established joint patrols, increased intelligence sharing, and formed a joint radar surveillance project. Issues remained regarding the employment of hot pursuit—one of the most indispensable tools for combating piracy, involving the right to chase pirates back to their lairs in another country’s territory.