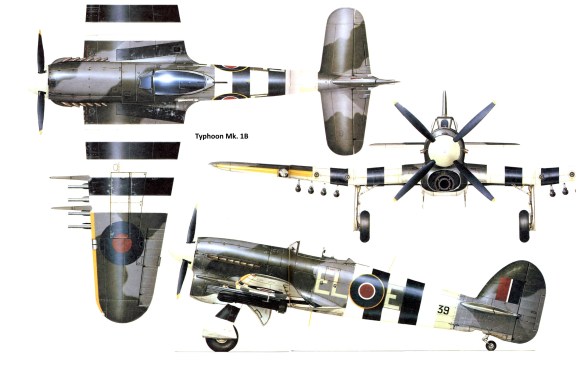

As a successor to the Hurricane, Hawkers had designed the Typhoon around the massive 24-cylinder Napier Sabre engine. The new fighter had a troubled gestation; engine and structural failures were all too frequent events. Although designed as a high-speed fighter, it lacked manoeuvrability, performance fell off with altitude, and at high speeds it became nose-heavy. In consequence, it was relegated to the close air support role.

If there was any campaign in WWII where conditions were perfect for airpower to demonstrate its ability to kill armour, it was in Normandy in the summer of 1944. The Allies had air supremacy (which is much more then just air superiority) and during daylight hours they could attack any target at will, with the single proviso of avoiding very nasty concentrated Flak guns. They had thousands of some of the best and most powerful ground attack aircraft available in WWII. They had virtually unlimited supplies of ammunition, fuel and huge amount of logistical ground support. Air bases were in easy range, targets were concentrated in a small front line area, and the weather could not realistically have been better.

According to the RAF, the Hawker Typhoon was the most effective ground attack and tank killing aircraft in the world in 1944, which may have been true. No fewer than 26 RAF Squadrons were equipped with Typhoons by mid-1944. These aircraft operated round the clock during the Normandy campaign operating in ‘cab rank’ formations, literately flying above the target area in circles, waiting their turn to attack. Official RAF and USAF records claim the destruction of thousands of AFVs in Normandy. There are many examples such as:

During Operation Goodwood (18th to 21st July) the 2nd Tactical Air Force and 9th USAAF claimed 257 and 134 tanks, respectively, as destroyed. Of these, 222 were claimed by Typhoon pilots using RPs (Rocket Projectiles).(2)

During the German counterattack at Mortain (7th to 10th August) the 2nd Tactical Air Force and 9th USAAF claimed to have destroyed 140 and 112 tanks, respectively.(3)

On a single day in August 1944, the RAF Typhoon pilots claimed no less than 135 tanks as destroyed.(4)

So what really happened? Unfortunately for air force pilots, there is a small unit usually entitled Research and Analysis which enters a combat area once it is secured. This is and was common in most armies, and the British Army was no different. The job of The Office of Research and Analysis was to look at the results of the tactics and weapons employed during the battle in order to determine their effectiveness (with the objective of improving future tactics and weapons).

They found that the air force’s claims did not match the reality at all. In the Goodwood area a total of 456 German heavily armoured vehicles were counted, and 301 were examined in detail. They found only 10 could be attributed to Typhoons using RPs (less than 3% of those claimed).(5) Even worse, only 3 out of 87 APC examined could be attributed to air lunched RPs. The story at Mortain was even worse. It turns out that only 177 German tanks and assault guns participated in the attack, which is 75 less tanks than claimed as destroyed! Of these 177 tanks, 46 were lost and only 9 were lost to aircraft attack.(6) This is again around 4% of those claimed. When the results of the various Normandy operations are compiled, it turns out that no more than 100 German tanks were lost in the entire campaign from hits by aircraft launched ordnance.(7) Thus on a single day in August 1944 the RAF claimed 35% more tanks destroyed than the total number of German tanks lost directly to air attack in the entire campaign!

Considering the Germans lost around 1500 tanks, tank destroyers and assault guns in the Normandy campaign, less than 7% were lost directly to air attack.(8) The greatest contributor to the great myth regarding the ability of WWII aircraft to kill tanks was, and still is, directly the result of the pilot’s massively exaggerated kill claims. The Hawker Typhoon with its cannon and up to eight rockets was (and still is in much literature) hailed as the best weapon to stop the German Tiger I tank, and has been credited with destroying dozens of these tanks in the Normandy campaign. According to the most current definitive work only 13 Tiger tanks were destroyed by direct air attack in the entire campaign.(9) Of these, seven Tigers were lost on 18th July 1944 to massive carpet bombing by high altitude heavy bombers, preceding Operation Goodwood. Thus at most only six Tigers were actually destroyed by fighter bombers in the entire campaign. It turns out the best Tiger stopper was easily the British Army’s 17pdr AT gun, with the Typhoon well down on the list.

Indeed it appears that air attacks on tank formations protected by Flak were more dangerous for the aircraft than the tanks. The 2nd Tactical Air Force lost 829 aircraft in Normandy while the 9th USAAF lost 897.(10) These losses, which ironically exceed total German tank losses in the Normandy campaign, would be almost all fighter-bombers. Altogether 4 101 Allied aircraft and 16 714 aircrew were lost over the battlefield or in support of the Normandy campaign.(11)

(2) P. Moore, Operation Goodwood, July 1944; A Corridor of Death, Helion & Company Ltd, Solihull, UK, 2007, p. 171.

(3) N. Zetterling, Normandy 1944, J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc, Winnipeg, Canada, 2000, p. 38.

(4) S. Wilson, Aircraft of WWII, Aerospace Publications Pty ltd, Fyshwick, ACT, Australia, 1998, p.85.

(5) P. Moore, Operation Goodwood, July 1944; A Corridor of Death, Helion & Company Ltd, Solihull, UK, 2007, p. 171.

(6) N. Zetterling, Normandy 1944, J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc, Winnipeg, Canada, 2000, pp. 38 and 52.

(7) N. Zetterling, Normandy 1944, J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc, Winnipeg, Canada, 2000, p. 38.

(8) N. Zetterling, Normandy 1944, J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc, Winnipeg, Canada, 2000, p. 83.

(9) C.W. Wilbeck, Sledgehammers, The Aberjona Press, Bedford, Pennsylvania, 2004, p. 131, table 4.

(10) N. Zetterling, Normandy 1944, J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc, Winnipeg, Canada, 2000, p. 38. Note, these losses include losses sustained attacking vital rear areas including railroads and bridges, where the real damage to the German effort in Normandy was done. Nevertheless the majority of Fighter Bomber losses were due to Flak protecting combat units.

(11) S. Badsey, Normandy 1944, Osprey Military, London 1990, p. 85

#

Air power cannot take and hold territory. The defeat of Nazi Germany demanded that the Allies invade the continent of Europe. The place selected was Normandy, the date was 6 June 1944, and the operation was called Overlord. Two essential preconditions were that army and navy invasion preparations should be concealed beforehand, and that absolute air superiority be maintained during and after the operation.

Preparations had been in hand since November of the previous year, with the formation of the 2nd Tactical Air Force RAF. This was later joined by the American 9th Air Force. As troops massed in southern England, and the invasion fleet gathered in the Channel ports, an air umbrella was thrown over the area. The Germans knew that an invasion was coming, they could guess at its timing, but with air reconnaissance made impossible, they completely failed to predict its location.

From D-Day onwards, the area of the landings and far inland was saturated with Allied fighters. For three months this intense pressure was kept up. Between 6 June and 5 September-by which time the German army was in headlong retreat-an incredible 203,357 Allied fighter sorties were flown; an average of more than 1,600 each day. After a slow start, the Luftwaffe put up 31,833 sorties during the same period. Outnumbered by more than six to one, 3,521 German aircraft were lost; an unsustainable 11%. Allied losses were a mere 516; one quarter of one percent.

At this stage of the war new fighter aces were very rare birds indeed. For the Allies, opportunities were lacking. In the period under discussion, it took nearly 58 Allied fighter sorties for each German fighter brought down. Under these circumstances, even experienced flyers had difficulty in adding to their scores.

As the tidal waves of Allied troops and armour rolled across France and up through the Low Countries, the Luftwaffe sought vainly to stem the advance in the face of overwhelming air superiority. Consequently they were generally to be found at medium and low altitudes, and this was where most combats took place. Many Allied fighter squadrons were also heavily committed to close air support and interdiction, to the disgust of many who now found their sleek Spitfires laden with bombs. However, this brought its own reward. ‘Johnnie’ Johnson’s 144 Wing discovered that bomb shackles could be adapted to carry beer barrels, and a service was laid on to keep the wing supplied.

Even at high altitudes, wing formations had been difficult to lead effectively. Lower down, in the tactical flying that now took place, they were far too cumbersome, and in addition were all too easy to spot from a distance. Most wing leaders now reverted to using single squadrons, albeit often with two or more in the same general area to give mutual assistance if the going got tough. The Luftwaffe also reverted to smaller formations than of yore, flying in Staffel strength and only rarely in Gruppen.

The ever-lengthening lines of communication made the problems of keeping such massive armies supplied too great until such time as the port of Antwerp could be opened. This was not done until early November, and the Allied offensive ground to a halt. This, coupled with worsening weather, gave the Luftwaffe a breathing space, in which the fighter arm was expanded using pilots from disbanded bomber units and re-equipped with new aircraft. At this stage the Jagdflieger was of very mixed worth; undertrained and inexperienced pilots, leavened with old stagers who were very dangerous but too few in number, equipped with fighters that were basically good, and in some cases excellent, but were only effective in the right hands. From October 1944, they were increasingly handicapped by a shortage of fuel.

Allied fighter units advanced to bases near the German border, which enabled them to range deep into Germany. From this point on, fighter operations became inextricably linked with the American long-range escort missions, even though they were not an integral part of them.

What amounted to the last throw of the Luftwaffe came at dawn on 1 January 1945, with Operation Bodenplatte. This was an all-out assault on Allied airfields on the continent by 800 or more fighters. While this destroyed almost 300 Allied aircraft, Jagdflieger losses were horrendous; many irreplaceable fighter leaders went down during this operation. The attack caused a hiatus in Allied fighter operations, the brunt of the air fighting for the next week or so being borne by the Tempests of 122 Wing, which had escaped the onslaught. The Jagdflieger never recovered. From this moment on they were encountered in the air only infrequently, though the fuel shortages meant that those met with were more than likely to be Experten. In spite of this, a handful of Allied fighter pilots managed to build up respectable scores, even though opportunities were few.