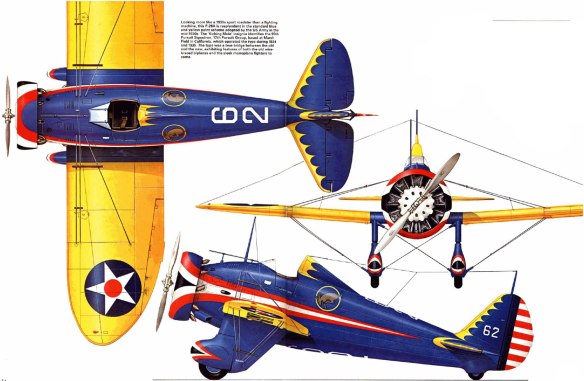

Looking more like a 1930s sport roadster than a fighting machine, this P-26A is resplendent in the standard blue and yellow paint scheme adopted by the US Army in the mid-1930s. The ‘Kicking Mule’ insignia identifies the 95th Pursuit Squadron, 17th Pursuit Group, based at March Field in California, which operated the type during 1934 and 1935. The type was a true bridge between the old and the new, exhibiting features of both the old wirebraced biplanes and the sleek monoplane fighters to come.

Just after Pearl Harbor, when Philippine air force pilots in the Boeing P-26 were outclassed and outfought by the formidable Mitsubishi Zero, it was fashionable to berate the ‘Peashooter’ as a dated and doughty pursuit ship. The P-26 had fixed landing gear with heavy, high-drag wheel pants. It was festooned with bracing wires. Its armament of two 0.3-in (7.62-mm) or one 0.3-in (7.62-mm) and one 0.5-in (12.7-mm) machine-guns seemed hopelessly inadequate. P-26s battled Japanese invaders in the Philippines and in China (which acquired-11 export machines) but were badly mauled. In those dark days of World War II it would have been easy forget that the P-26 of 1931 had been a bold new venture in fighter design: the first all-metal fighter and the first monoplane fighter to enter squadron service. The P-26 was also the final production fighter built by Boeing, which had dominated the field for nearly two decades.

Ordered by the US Army on 5 December 1931 initially with the designation XP-936, the ‘Peashooter’ made its first flight on 20 March 1932. The prototype machine (32-412), one of three covered by the contract, differed from the familiar production model (Boeing Model 266) in having a lower headrest for its open canopy, and wheelpants which extended behind the main landing gear struts. No beauty, with a huge Townend ring enclosing its 525-hp (391.5- kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1340-21 radial air-cooled engine, an improved version of the powerplant used by the P-12 biplane fighter, the P-26 nevertheless impressed the onwatcher with its sleekness by comparison with biplane fighters of the time, including the P-12 itself which was still in production. Shortly after the third machine (32-414) reached Selfridge Field, Michigan, on 25 April 1932 to be evaluated by operational pilots, the Army formally purchased the first three airframes from Boeing and designated them XP-26, later YZP-26 to indicate the service-test function and, later yet, simply P-26. With improved headrest and other minor changes, the P-26A was ordered into production on 28 January 1934 with an initial buy of 111 airframes (33-28138). There followed two P-26Bs with fuel injection (33-179 and 33-185) and 23 P-26Cs (33-181/203), the latter with 600-hp (447.4kW) R1340-27 engines.

Some ‘greats’ of the era flew the P-26. Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Royce (later a major general) at Selfridge Field, Michigan, was fond of it. Major General Frank O. Hunter of the 17th Pursuit Group at March Field, California, sung its praises. Major Armin F. Herold of the 20th Pursuit Group at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, led formations in a P-26A gaudy with blue, yellow and red bands around the engine cowl. In fact, ‘Peashooters’ appeared widely with elaborate paint schemes. Those of the Bolling Field Detachment, Washington, DC, had alternating blue and gold squares on their Townend rings and around the capitol insignia on the rear fuselage, with yellow tail and red/white striped rudder surfaces. Perhaps most impressive were the mostly blue machines, with red, yellow and gold trim, operated by the 95th Attack Squadron at Selfridge. Major Peter Schwenk, a pilot with that unit, recalled that his Boeing ‘looked like a flying neon sign’. In all, ‘Peashooters’ served with the 3rd, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th, 27th, 32nd, 34th, 38th, 55th, 734 77th, 79th, 94th and 95th squadrons.

‘Hot’ ship

In the 1930s, the Boeing monoplane was a ‘hot’ ship. With a maximum level speed of 227 mph (365.3 km/h) at 10,000 ft (3048 m) and an initial climb rate of 2,300 ft (701 m) per minute, it was highly manoeuvrable. It outclassed the biplane P-12 in every performance regime. On landing, where it required careful control and did not forgive the lax flier, the P-26 was too hot. Its 82.5 mph (132.8 kmh) landing speed made it difficult to handle until flaps were developed by the Army, reducing landing speed to 70 mph (112.7 km/h). The flaps were retrofitted on P-26As and installed on P-26B and P-26C machines on the production line. Flying the P-26 was a thrill. “That open cockpit and high manoeuvrability kept you in touch with the elements,” says Schwenk. The high, sturdy headrest found on the fourth airframe onward resulted from an accident when an early P-26 flipped violently on its back and killed the pilot with almost no structural damage to the aircraft. “It was sturdy,” says Schwenk. “Though we never flew it in combat, we had the feeling it could take punishment!’ Though its landing gear was stalky and its approach characteristics, as noted, were demanding, the P-26 was easy on the touch once aloft and pilots were pleased that it evoked a feeling of power and toughness. It was a mainstay between world wars until replaced by the Seversky P-35 and Curtiss P-36 in the late 1930s.

In addition to the Philippines, US Army P-26s ended up in the air forces of Panama and Guatemala. The latter country was valiantly flying ‘Peashooters’ as late as 1957. The final variant, the Boeing Model 281, did not enter US service or receive a P-26 designation, although identical to the US machine: 11 went to China and one to Spain. A P-26 occupies a place of pride at the US Air Force Museum in Dayton. Ohio.