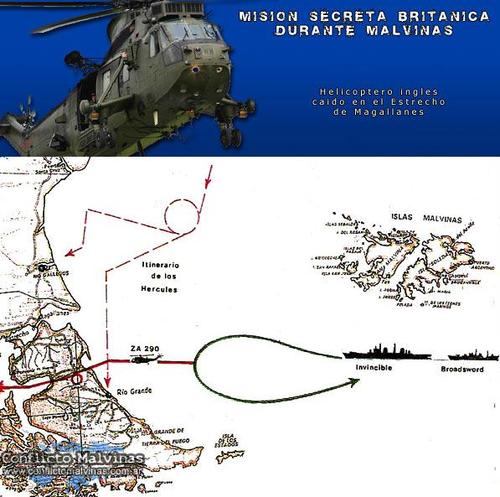

Suspicious appearance. The remains of the Sea King helicopter, dropped in 1982 in Punta Arenas. We now know that was part of Operation Mikado.

The planned drop-off point for the Special Forces team had been a point close to an isolated estancia twelve miles to the north-west of the Rio Grande airbase. In the increasingly adverse weather and deteriorating visibility Hutchings put his aircraft down seven miles short of the designated drop zone, in the vicinity of an isolated farm called Cerro Seccion Miranda, Tierra del Fuego. In the circumstances this was a fi ne achievement by the crew of the Sea King.

The SAS Captain had been listening and talking to the Sea King’s crew throughout the flight. As they landed he moved up to the front of the helicopter so that Wiggy Bennett could point out to him their exact location on the map. After a few moments Captain `A’ announced that he was aborting the mission.

The SAS leader said that he did not have any confidence in the aircraft being exactly where Wiggy declared it to be. The SAS officer felt that in not being certain where he was, the risks had become too great. Captain `A’ refused to accept that the grid reference of their position was accurate, despite the helicopter’s navigation equipment having been updated on a known landmark only fifteen minutes earlier. Despite the Fleet Air Arm crew’s “best endeavours” to persuade him to the contrary, Captain `A’ therefore decided to abort the mission and asked Hutchings to fly him and his men to Chile.

Captain `A’ broke the news to his men, three of whom had already stepped down from the Sea King on to Argentine soil. “I’m sorry”, he shouted, “it’s Chile after all”. With these words, the daring strike against the Argentine airbase came to an end.

The troopers re-embarked and the Sea King lifted off once again. The danger, however, was far from over. They were still in enemy territory, their fuel was critically low and visibility was near zero. The priority now was to cross into Chile as soon as possible, before the Argentines discovered their presence.

Shortly after Hutchings took off, as he was forced to climb to a higher altitude to pass over the Carmen de Silva mountain range separating southern Argentina from Chile, the Sea King’s radar warning receiver began to squawk insistently in the crews’ headphones, alerting them to the fact that they had been detected by hostile radar. They could only pray that the Argentines at Rio Grande would dismiss the radar contact as one of their own aircraft.

“The aircraft had been detected, the Argentineans at Rio Grande knew that there was a slow-moving aircraft flying on an opening vector from the area of the air base,” noted Hutchings. “The tension in the aircraft was characterised by our near silence. Our long transit from Invincible to the Argentine coast had been quite a chatty affair, but now our silence was punctuated by essential dialogue only. All the time, we were close to being mesmerized by the radar pulses loud and clear in our headsets.”

Several terrifying minutes later, during which the crew feared being blown out of the sky at any moment by a surface-to-air missile, the Sea King finally crossed into Chilean airspace. The helicopter’s fuel state was by now perilously low.

During the planning of the operation three potential locations for landing and destroying the helicopter had been selected. Which of these would actually be chosen by the helicopter crew would be dictated by a combination of factors, including the amount of fuel available at the time and visual observation. As it transpired, fuel was the determining factor.

It was agreed that the SAS should be dropped off first, to make their escape separately, and then Hutchings would find a safe place to land and destroy the Sea King as far from the SAS team as possible. When Hutchings placed the helicopter firmly down on Chilean soil, he indicted to the SAS Captain where they now were. Captain `A’ agreed that this was the best of the three proposed landing spots as it was the only one which afforded direct land access to Argentina, if that should later be required.

After the SAS had disembarked, Hutchings flew on until he found a secluded beach at Agua Fresca, some eleven miles from the town of Punta Arenas, to set his aircraft down.

In the original planning for the mission it had been decided that the helicopter would be ditched in deep water. After chopping holes in the aircraft fuselage with an axe and survival knife, Hutchings took the aircraft out to sea and dropped it gently onto a flat sea, his aim being then to swim ashore. But so calm was the water, the Sea King refused to sink. Hutchings had no choice but to fly the helicopter back to the beach and destroy the machine, along with all the sensitive equipment, with explosives and fuel.

For the next eight days the three men made their way the request of the Chilean authorities a press conference was hastily arranged in which Hutchings delivered a prepared statement. In this he again repeated the story given to the Chilean authorities: “Whilst on sea patrol we experienced an engine failure. Due to adverse weather conditions it was not possible to return to our ship in this condition. We therefore sought refuge in the nearest neutral country”.

The press was not convinced. With speculation intensifying, that same day the three men were hurriedly flown out of the country by embassy officials.

In the years since the operation, Hutchings has discovered just how lucky he and the others onboard “Victor Charlie” had been:

“Over the years I have struck up acquaintances with a number of former conscripts, professional soldiers and marines whose role in 1982 was the defence of the airfields and aviation fuel storage tanks in Patagonia. I now know the detailed dispositions of Argentine troop deployments across that region during the war.

“As we skirted north around the gas platform in the Carena field, our aircraft was detected by one of two Argentine frigates patrolling close to the coast and no more than three miles away from `Victor Charlie’. The performance of our rather rudimentary first generation radar warning receiver was poor and was unable to detect the ship’s radar propagation. The ship could not engage us because of our close proximity to the gas platform. Then, as we flew south across San Sebastian Bay we came within a quarter of a mile of an aviation fuel dump which was heavily defended by a company of marines. They heard the aircraft, but thanks to the fog could not see it – just as well because we were well within the range of their weapons. It also transpires that the intended landing location was defended by a company of marines – a landing there would have probably resulted in the helicopter’s destruction. In addition, there were frequent patrols of the surrounding area by foot, vehicle and helicopter.

“The Argentines had the Patagonian coastal area sown up pretty tight utilising infantry, armour, artillery, engineers, aviation assets and warships. Attempts to disrupt Argentine air operations through acts of sabotage at the airfields and fuel stocks by our Special Forces had been long anticipated by the Argentine military planners and around 10,000 troops were assigned to the defence of the area. There was no intelligence available to the Task Force of any of the military defences and activity in Patagonia – we were flying blind.”

The failure of Plum Duff convinced the British commanders that Operation Mikado, the full-scale airborne assault on the Rio Grande air base, was no longer a practical proposition. The plan was quietly dropped.

Tragically, the deadly threat posed by the Exocet was underlined on 25 May, when Super Étendards operating out of Rio Grande scored another success, sinking the large container ship Atlantic Conveyor. However, it could have been even worse. This Exocet is believed to have first locked on to HMS Invincible, which was in the same area, but at the last moment was decoyed away by “chaff” – strips of aluminium foil fired into the air to confuse the missile’s onboard radar.

With hindsight, however, it was just as well that the mission to destroy the Super Étendards and their Exocet missiles had been cancelled. After the war, it was discovered that the Rio Grande base had been defended by no less than four battalions of well-trained marines – far more than the SAS had anticipated. At the same time, the Super Étendards aircraft had been moved, in early May, to fortified revetments positioned along the coastal highway, each heavily defended.

If Mikado had gone ahead, the sardonic nickname given to the operation by members of the elite unit, “Certain Death”, may well have proven to be all too accurate.