Waffen-SS-Division – Wiking

In theory, the Waffen-SS was forced because of its status to recruit only volunteers. In reality, an increasing number of men were pressured into joining the Waffen-SS during the conflict. The question is, therefore, when and by what means the SS overrode its own principles and broke both German and, in the case of foreigners, international laws by enlisting non-volunteers. Contrary to preconceived ideas, the pressure on “volunteers” did not evolve in a linear fashion during the conflict. The application of coercion fluctuated, depending both on SS needs and on available manpower. As early as spring 1940, when the SS wanted to complete its “Death’s Head” regiments, civil SS members, teenagers of the Patrol Service and the Hitler Youth, and even members of the SA were pressured to enlist in the Waffen-SS. A rise in enforced enlistments occurred again one year later, just before the invasion of Russia, when the SS had to fill up its active and reserve units, in the form of a “20,000 men campaign” within a period of seven weeks.

The transformation of the Waffen-SS into a mass army in the years 1942-3 certainly marked a clear breach of earlier practices. From this point onwards, coercion was no longer applied only to men who were more or less closely connected with a SS or Nazi organization, but also to common conscripts. The recruiting methods did not change, but the population affected by them did.

The increasing scarcity of manpower in the Reich also contributed to this evolution. The growing need for soldiers, particularly due to the Wehrmacht’s losses in Russia, obliged the army to enlist ever younger age groups. From the end of 1942, the number of age groups available for enlistment was reduced to only one (year class 1925), while there had been three at the beginning of the year. Consequently, constraint took on a cyclic form: each time a new age group was available to be enlisted, the SS and Wehrmacht had no difficulty in finding a certain number of enthusiastic young volunteers. But these volunteers did not suffice. For the Wehrmacht, the problem was easily solved by conscription. The SS, however, had to increase the pressure on the passive members of each age group to fill its ranks.

With regard to enlistment, the SS was not as powerful within the Reich as is believed in current secondary literature. A number of cases prove that it was possible to avoid enlistment in the SS, at least by enlisting in the Wehrmacht. The existence of complaints proves, also, that it was possible to oppose an arbitrary decision. In February 1943, for example, 2,500 teenagers who had been coerced to enlist in the Waffen-SS were released and handed over to the police.

Enforcement sometimes took radical forms, including the death penalty at times. Still, this was only possible by consent of both Hitler and the Wehrmacht high command. On the other hand, the SS found in the army an increasingly dangerous competitor for recruits, since in summer 1943 the army started to use the same methods as the SS, only on a larger scale. The figures speak for themselves: enforcement did not lead to an increase in SS enlistments. In fact, the number of new recruits in the Waffen-SS diminished in 1944 in favour of recruitment into the army. Nonetheless, since both air and sea were controlled by Allied forces, the course of the war necessitated the dispatch of Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine soldiers to ground-battle units. If the Army (Heer) received the greatest part of them, the Waffen-SS received, for its part, about 40,000 men, because Himmler had meanwhile been designated Chief of Army reserve, after the assassination attempt on Hitler of 20 July 1944, and so could give some advantages to “his” Waffen-SS. As these men had no choice, it is hard to say whether or not they accepted their transfer willingly. Some of them were satisfied; others protested in vain – not always for political reasons, but also due to being “loathe to become common infantry.” Hence, as has recently been shown by the case of the German Nobel prize winner Günter Grass, who confessed to having belonged to the Waffen-SS after having volunteered for the submarines, towards the end of the war it became increasingly difficult to make a distinction between real volunteers and others.

This is also true for the Volksdeutsche. While the SS took much care to stress the voluntary character of the enlistment of “ethnic” Germans at the beginning of the war, it began to use more forceful tactics when it failed to achieve its recruiting objectives in 1942, at the time of the formation of the “Prinz Eugen” division with men of the former Yugoslavia. Himmler even decreed the conscription of the Balkans’ Volksdeutsche from 17 to 50 years old, “if necessary to 55 years old”. They had, according to him, the duty to serve “not by formal law, but by the brazen law of their Volkstum”.

This unilateral decision complicated the matter rather than resolving it. It was, in fact, very hard to enforce, for many reasons. Himmler’s main chiefs of staff were opposed: for the chief of SS recruitment, the results would be counterproductive, because enlistment into the SS would be seen as a punishment; for the military chief of staff, the results on the battlefield would be poor with such conscripts; finally, it would be impossible to publish this decision, for propaganda and diplomatic reasons. Consequently, the issue of general conscription for the Volksdeutsche remained unresolved until the end of the war. In itself, it had no more importance. As the SS judge in Himmler’s office wrote in February 1945, “the SS and police courts had always taken care of the Reichsführer’s point of view, even without such legal basis, and […] used it as fundament of their decisions with all consequences which proceeded from it.”

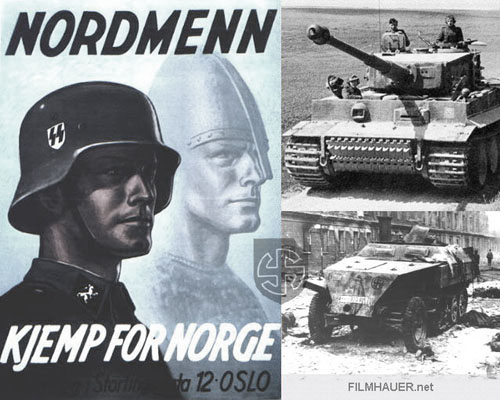

During the war, the SS paid much more attention to the voluntary character of enlistments of “Germanic” foreigners in the occupied countries than of Germans in the Reich. More than the will to adhere to the international laws of war, the racial conceptions of the SS can explain this choice. The SS, for example, respected its engagements and liberated its “Germanic” volunteers who had enlisted for a short six-month service. Even men who wanted to go home before the end of this period were released in March 1941. In October 1942, more than 20 per cent of the “Germanic” SS volunteers had been released from armed service since the beginning of the war, while 2,404 out of 10,821,509 had been killed (4.7 per cent). Of course, there were cases of constraint, especially from 1943 onwards. But these remained at a very low level. And, although Himmler considered introducing conscription in the “Germanic” countries, he did not do so. By contrast, the SS dealt otherwise with “non-Germanic” volunteers. In fact, it rounded up the young male inhabitants of some countries when it needed men, for example in Zagreb when the Bosnian Division was set up in summer 1943. Men were also rounded up to fill the ranks of the Second SS Armoured Corps in Ukraine, in spring 1944. Such operations were not, however, a “Waffen-SS exclusivity”. Finally, conscription was introduced in 1944 in Bosnia, Estonia, and Latvia.

To sum up, it has become clear that the profiles of the Waffen-SS volunteers are much more complex than is usually believed. Even more important, independently of their profiles or their motivations, these volunteers came to serve as an example after which the Reichsführung SS and the government intended to model the Wehrmacht. In the competition created by the Nazi leaders between the “conservative” German army and the “revolutionary” Waffen-SS, the latter gradually became the model of reference regarding efficiency on the battlefields – or so, at least, it was successfully represented by propaganda. The ideological conviction of these “new types of political combatants” was declared as more important than their professional value. Furthermore, through the successful enlistment of foreigners, the Waffen-SS gave the illusion that patriotism was henceforth transcended by ideological education. Given this example, the German Army was intended by the government to evolve in the same direction. The army’s Volksgrenadier-Divisionen, which were set up under the aegis of the SS even before the attempt on Hitler in July 1944, and later the Volkssturm were means of copying this ideological “success”. They were a direct extension of the social model of the Waffen-SS to the regular army, and by the end to a whole society at war.