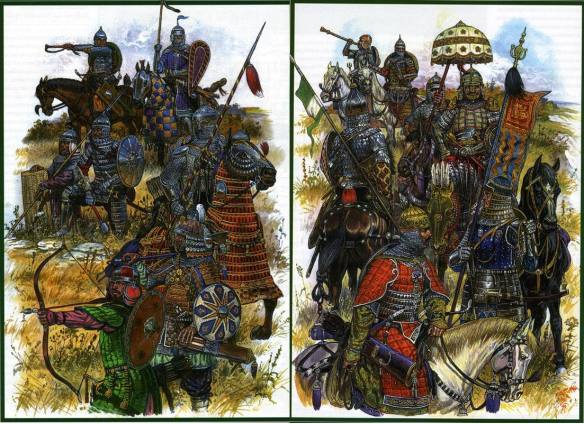

Mongol Warriors of the Golden Horde

The Mongol conquest profoundly affected the natural evolution of medieval, or Kievan, Russia, but there is no agreement among the experts as to the nature and extent of its impact. It was a traumatic experience, coming only thirty-eight years after the fall of Constantinople to the Latin crusaders in 1204. This was also a considerable shock to the Orthodox Rus’, whose religious capital was now in the hands of schismatics, and who had to look to Nicaea for ecclesiastical direction until 1296.

The Mongol conquest destroyed the remaining unity of Kievan Rus’. A good deal of the south-western part of the old Kievan grand principality, including Kiev itself, which had been devastated, came under direct Mongol rule, and by the fourteenth century had been absorbed, mainly by conquest, into the Grand Principality of Lithuania. As a result Kiev went one way and the city of Vladimir on the Kliaz’ma, founded in 1108 by Prince Vladimir Monomakh, went another, with consequences which will be discussed below. The principalities gravitating around the city of Vladimir, in the north-east, and the republic of Novgorod in the north continued under their own princes, subject to Mongol approval. The character of the north-eastern principalities defined the new community which arose around it. The climate was harsher, the winter was longer, the forest was denser, the days were shorter in winter though longer in the brief summer than in Kievan Rus’. Communication with the Eastern Roman Empire or central Europe was more difficult, and settlement was more recent in the north-east. The independent city republic of Novgorod was held by the Mongols on a somewhat loose rein, but it too formed part of the Mongol empire since its trade was of considerable importance to these rulers of the steppe.

Not only was the zemlia or land of Rus’ thus divided, the north-east and the south-west losing touch with each other, but the fairly continuous contacts with eastern and central Europe which had marked the old ruling élite and the merchant class were much reduced – except for the city republics of Novgorod and Pskov, which continued to trade with the Hanseatic League, and the trade with the West which trickled through Smolensk. Vladimir and Moscow now participated more in trade ventures to the Middle East. There were no more Riurikid marriages with European royal and princely houses. There were some marriages with the Mongol ruling house, but not many after the conversion of the Golden Horde to Islam in 1340.

The Mongols did not settle in Rus’, since the land was not suitable for the nomadic life which was the basis of the economy on which their huge cavalry army relied. Khan Baty established his capital in Saray, on the lower Volga, and summoned the Russian princes repeatedly to Saray, or sent them on to the Mongol capital Karakorum, in Mongolia, to have their iarlyki (patents to rule) renewed. This long journey was so exhausting that several princes, notably Alexander Nevsky, died on the way or the way back.

The khan of the Mongol empire had to be chosen among the descendants of Genghis Khan, the Golden Kin. Hence the Mongols were quite prepared to accept the Russian principle of confining the choice of princes to a ruling family, the Riurikids, descendants of the semi-mythical Scandinavian prince Riurik, and frequently accepted the choice made by the Russians, though they did not hesitate to reject it when they preferred another candidate. Their policy broadly was not to allow any principality to become too strong. They delegated the task of collecting the heavy tribute imposed on the Russian lands to the princes, and eventually to the ruler of Moscow, though the assessment was made by Mongol officials. It is estimated that in the late fourteenth century the principality of Moscow paid between five and seven thousand rubles a year, a very large sum bearing in mind that this was not the only financial burden.

There has been much debate among historians on the scale of the physical destruction inflicted by the Mongol invasion, on the nature of Mongol influence on Russian social and political development, and the extent of Mongol responsibility for the perceived backwardness of sixteenth-century Russia. To understand the initial impact of this calamity on the Russians many factors must be considered: its suddenness, the destruction of the economy, the depopulation by death and enslavement and by the conscription of potential soldiers and craftsmen, the loss of skills, the plundered cities and devastated fields, all occurring with the speed of a whirlwind, and recurring whenever the Mongols thought the Russians needed a reminder of their subordinate status. The princes, who may well have been relatively protected from the worst effects of the conquest, had to learn to manoeuvre, to intrigue, lie and bribe, in order to achieve their ends, to submit to the demands of their masters, however humiliating.

Inevitably most of the Russian written sources dealing with this period are biased against a people whom they saw as a cruel and destructive oppressor belonging to an alien faith, the Ishmaelites or sons of Hagar. Yet Russians and Mongols frequently cooperated on the battlefield, there was some intermarriage, and judging by relationships in the sixteenth century, there was no deep-seated racial prejudice. Moreover, the Russian ulus was but a small and relatively unimportant part of the vast lands ruled over by the Golden Horde. Hence most of the political and diplomatic activity of the Khans was oriented towards the East, where their power originated. The portrayal of the Mongols at this time as barbarians living in tents does not do justice to the sophistication of the imperial administration in the west, based on the capital Saray, on the lower Volga, where there was a luxurious court, the streets were paved and there were mosques for the Moslem Mongols and a Russian bishop to minister to the Russian community of craftsmen and soldiers in Mongol service, as well as caravanserais to lodge the vast trading expeditions.

However, from the latter part of the fourteenth century the Mongol hold on Russia was affected by discord within the Golden Horde. The victory of Dmitri Donskoi, Grand Prince of Vladimir and Prince of Moscow, supported by some other princes, over a Mongol force in 1380 at the Field of Kulikovo raised the prestige of Moscow among the Russian princes, though it was followed by a Mongol revival under Tokhtamysh, who razed Moscow in 1382. Tokhtamysh and his Russian allies in turn were destroyed by Tamerlane who, from his base in Samarkand, devastated Saray, but refrained from destroying Moscow. In the early fifteenth century the Golden Horde broke up into the Khanate of Crimea, the Khanate of Kazan’ and the Great Horde. The two sons of the Khan Ulug-Mehmed of the Golden Horde became vassals of Grand Prince Vasily II, and founded, under Russian protection, the Khanate of Kasimov, on the Oka River. Its Mongol ruler helped Vasily II to regain his throne in the Russian civil wars of 1430–36 and 1445–53, which arose out of the conflict between the traditional Russian principle of lateral succession to the throne (to the next eldest brother) and hereditary succession from father to son, the principle which emerged victorious from the struggle. It was against this background of conflict and confusion, of occasional alliances and occasional strife, that the final confrontation took place in 1480, on the River Ugra, between the remnants of the Mongol Great Horde, with its allies in the Crimea and in Poland–Lithuania, and a Muscovite army, with its Mongol allies, the khanates of Kazan’, Astrakhan’ and Kasimov, under Grand Prince Ivan III of Moscow. There was actually no battle, since both sides withdrew before the armies could engage. But from this date Moscow ceased to regard any Mongol horde as its overlord, though it continued to collect the tribute within Russia and distribute it as presents among its Tatar allies on a smaller scale. Muscovite leadership in the two major confrontations between Russians and Mongols, at the Field of Kulikovo in 1380 and on the River Ugra in 1480, as well as its victory in the fifteenth-century civil wars, reinforced the Russian perception that the Grand Duchy of Vladimir/Moscow had become the leading principality in Rus’, and Ivan III gradually asserted his sovereignty (samoderzhavie) over the remaining independent Russian principalities including, in a notional sense, those which now formed part of the Grand Principality of Lithuania (see below). The theological interpretation of this ‘victory’ also served to increase the authority of Moscow, for as the Tverian author of The Tale of the Death in the Horde of Michael Yaroslavich of Tver tells it, ‘God gave Jerusalem to Titus not because he loved Titus but to punish Jerusalem’. Thus victory came to Moscow to punish the unbelievers.

What, if any, influence did Mongol suzerainty have on the development of Muscovite absolutism? The idea of a universal empire instituted by God was fundamental to the Mongol conception of the world order and there was therefore, in their view, no point in resisting the Mongol army. Once the universal Mongol empire was established everyone would be compelled to serve it. The basic principles of Mongol rule were laid down in the Great Iasa, or Code, attributed to Genghis Khan, which regulated the universal service of subjects in the army and the administration, and proclaimed their duty to care for the sick and the old, to offer hospitality, and to produce their daughters in the beauty contests in which the ‘moonlike girls’ would be selected as wives or concubines of princes. The code also dealt with civil, commercial and criminal law, naming as offences acts against religion, morals and established customs, and those against the life and interests of private persons. The usual penalty was death.

The practical aspects of Mongol administration and the etiquette in use at the Mongol court were familiar to the Russians who visited Saray; Russians learnt to speak Turkic, and the Mongols probably learnt some Russian. It was perhaps the arbitrary nature of Mongol decisions which most affected Russians, but it may be that this apprenticeship in subservience prepared them for the obsequiousness they are alleged to have shown to the tsars of Moscow. Moreover, Russian grand princes, and many appanage princes, learnt subordination to the Mongols the hard way: between 1308 and 1339 eight princes were executed in the Horde, including four who had become grand princes of Vladimir.

The Mongol presence was not ubiquitous in Russia, and usually consisted of a limited number of officials, tax collectors, recruiting officers and platoons of cavalry. Yet by the sixteenth century many Russian princely families were stressing their descent from Mongol tsarevichi (sons of khans) or other nobles. The tsarevichi who descended from Genghis Khan took precedence over other princes in Moscow and ranked above or immediately below Riurikovichi until the end of the dynasty in Russia. Russian aristocrats could be proud of their descent from princely Mongol families, where they would have kept silent about descent from commoners.

It is not easy to be precise about the nature of Mongol influence, for it extended over more than two centuries and the Golden Horde itself went through many changes during that period, including the vital conversion to Islam. But the Russian aristocracy did have fairly close contact with the nomads of the steppe, and by a process of osmosis may well have acquired many habits and adopted assumptions about the objects of a state, the nature of government, relations between lords and vassals, masters and servants, that are difficult to detect today. There are two specific aspects of this contact which may have rubbed off on the Russians, namely the degree of cruelty which they actually felt and saw in the executions or in the inflicting of punishment practised in the Golden Horde, and the absence of orderly judicial procedures (they did not usually see Byzantine practices). Not that the Riurikid princes of Russia (or their Viking ancestors) were not capable of great barbarity, but on several occasions, recorded in the Chronicles, such barbarity is clearly regarded as wrong in a Christian country.