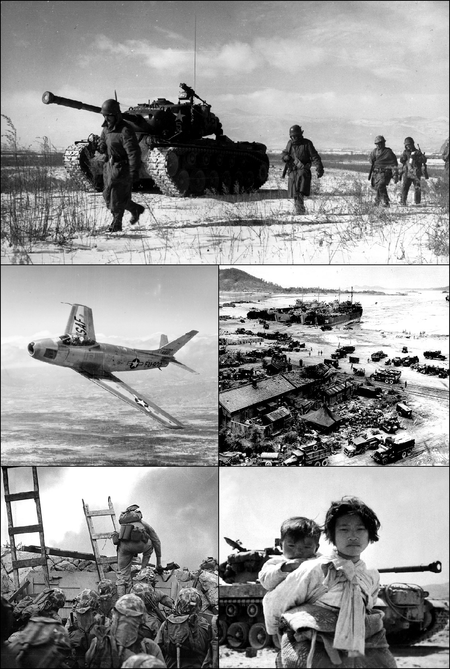

Clockwise from top: U.S. Marines retreating during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir; U.N. landing at Incheon harbor, starting point of the Battle of Inchon; Korean refugees in front of an American M26 Pershing tank; USS Princeton and F9F Panthers of VF-191 heading to Attack the Sui-ho Dam; Chinese dead on the approaches of The Hook during the Battle of the Samichon River; U.S. Marines, led by First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez, landing at Incheon; F-86 Sabre fighter aircraft.

All across Korea Chinese commanders held a low opinion of the American soldier. In the months of January and February 1951, this began to change. Under Ridgway U.S. troops fought well. And they fought successfully. By mid-March, Seoul, by now a city in ruins, was again in U.S. hands. Thirteen days later, American forces had crossed the 38th Parallel. Reaching the Imjin River, some thirty miles north of the city, they dug in.

So did the British brigade. Composed of Gloucester and Northumberland fusiliers (plus a Belgian unit), the brigade was deployed south of the river, some thirty miles north of Seoul, but in the middle of the route traditionally taken by those intent on capturing the capital. What followed, once the Chinese attacked, was a heroic but futile effort to halt the massive enemy advance. One company of Gloucesters, according to Michael Hickey (who had fought in Korea), was “on the verge of extinction . . . when there was a final radio call from the defenders: ‘We’ve had it. Cheerio,’ before the radio went dead.”

Ridgway expected a new Chinese offensive. This he received. Before the attack materialized, the general was given a promotion he had not expected. On April 11, Douglas MacArthur was fired and Matthew Ridgway became supreme commander of all U.N. forces in Korea.

MacArthur had issued several statements on the war that were contrary to U.S. policy. President Truman, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff all wanted to limit the conflict to the peninsula. General MacArthur sought a wider war. With support from influential Republicans in Washington, he advocated attacks on China and saw no reason not to employ nuclear weapons. Moreover, he felt that as Supreme Commander in the field, he, not Mr. Truman, should determine the course of action. Truman, whose standing in the public was as low as MacArthur’s was high, reacted to the general’s insubordination and sacked him. MacArthur left Tokyo and returned to America, receiving a hero’s welcome. He then sought the Republican nomination for president in 1952, but failed. The GOP delegates chose instead another general, one by the name of Eisenhower.

On April 22, 1951, the Chinese launched yet another major offensive, throwing 250,000 men at the Eighth Army, now commanded by Lieutenant General James Van Fleet (as a colonel Van Fleet had led troops onto Utah Beach in Normandy on June 6, 1944). The goal of the offensive and that of another one in May was, once and for all, to evict the Americans and their allies from Korea. The Communists, in what is called their Spring Offensive, were aiming for a decisive victory. They were willing to expend thousands of lives to achieve it. They achieved the loss of life, but not their goal. U.N. soldiers fought tenaciously, retreated a few miles, and held. Then they themselves attacked and pushed the Chinese back several miles.

There, for the next two years, the battle line was drawn. The war in Korea continued, with heavy casualties but little exchange of territory. Peace talks first began in July 1951. They concluded only in July 1953. During that time, the front lines, with trenches and fortified bunkers, resembled those of the First World War. Fighting was extensive. Individual hills were contested. Names such as Pork Chop Hill became legendary. But military gains and losses in any strategic sense were minimal. The Chinese could not drive the Americans into the sea. The United States was unwilling to accept the casualties necessary to push the Chinese back across the Yalu. Nevertheless, American forces suffered. Forty-five percent of U.S. casualties occurred after the peace talks began.

And so the war ended as it had started. Korea was cut in two, roughly along the 38th Parallel. In the north, Kim Il Sung remained in charge of a totalitarian state that still exists today. Then and now its citizens lack material comforts and are deprived of political freedom. In the south, the Republic of Korea continues. However, it is today economically prosperous and a democratic society. Nevertheless, sixty years after the Korean War, armies confront one another halfway down the peninsula. One of them is the United States Eighth Army. This time it is well trained and well equipped. It serves as a deterrent to war and a reminder of a bloody conflict now largely forgotten.

Why did the North Koreans attack across the 38th Parallel?

Kim Il Sung sent his army south in order to place the entire Korean peninsula under his control. Historically, Korea was a single entity, not two separate countries. Kim believed his destiny was to reestablish a unified Korean nation, this time as a Communist state. Moreover, he believed that most South Koreans would welcome the arrival of their northern brethren and that the Americans either would not contest the invasion or, if they did, would be easily defeated. On all three counts Kim was wrong.

Before launching the attack, Kim Il Sung secured Stalin’s approval for his action. Indeed, Russian generals helped plan the invasion and provided much of the equipment used by the North Koreans.

The Soviet leader assumed the Americans would not respond militarily to Kim’s invasion. The Americans he knew were not prepared for war and were interested in Japan, not Korea. Moreover, like Kim, Stalin had noticed that America’s secretary of state had not included Korea when listing territories of importance to the United States.

Why did the Chinese intervene?

The Chinese entered the war in late November 1950, just five months after the conflict began. They did so because an American army was advancing toward their border (the Yalu River being the boundary between North Korea and Manchuria, a part of China). This army was led by a general, Douglas MacArthur, who espoused extreme hostility toward the new rulers of China and their political ideology, and who seemed to have no qualms about employing nuclear weapons. Quite rightly, the Chinese Communists were concerned. They decided to take steps necessary to protect their country.

For several reasons, the Chinese leaders, including but not limited to Mao, saw the Americans as sworn enemies of the state. After all, it was the Americans who had supported their rival Chiang Kai-shek in the bloody contest for control of China. It was the Americans who, with their fleet off Formosa, prevented the Chinese from “liberating” the final piece of Chinese territory over which the Communists did not rule. And it was the Americans who prevented the Chinese in Peking from representing China in the United Nations. With good reason the rulers of China viewed the Americans with distrust and alarm.

Did the Chinese win the Korean War?

They certainly believe they did. From late November 1950 through January 1951 the Chinese army crushed the Americans in battle, causing both the U.S. Eighth Army and X Corps to retreat in humiliating fashion. This victory brought the Chinese great prestige abroad and, at home, remains a source of pride. That the Chinese army suffered enormously high casualties in the effort seems to have been forgotten, or is simply ignored. Nor does it register with the Chinese that, while they defeated the Americans in late 1950 and early 1951, they did not destroy the American forces, which, had their army been more capable, was an outcome within reach. Once Matthew Ridgway took command of the U.S. Army in Korea, the Chinese were unable to push the Americans off the peninsula, which, on several occasions, they attempted to do.

Nonetheless, the Chinese army had beaten the West’s most potent military. In doing so, it had kept the Americans away from the Yalu (for the Chinese, a decidedly positive accomplishment) and saved the regime of Kim Il Sung (a more dubious one). So they can claim a victory, although the eventual outcome of the war and the casualties the Chinese incurred suggest the win was far from complete.

The narrative refers to other nations providing symbolic contributions to the U.N. effort in Korea. Which countries were they and what did they provide?

Australia, Canada, Great Britain, the Philippines, Thailand, and Turkey all sent ground troops to Korea, although their numbers were small relative to those of the United States. So did Belgium, Ethiopia, France, Greece, and the Netherlands. As did New Zealand, which, in addition, deployed naval vessels, all frigates.

Canada also contributed to U.N. maritime forces, sending several destroyers to Korean waters. Australia sent an aircraft carrier, HMAS Sidney, along with escorts. However, the largest naval contingent, outside that of the United States, came from the United Kingdom. The Royal Navy kept one of three carriers on station throughout the conflict. One of these, HMS Triumph, on July 3, 1950, launched twenty-one aircraft that attacked a North Korean air base. This was the very first day of naval strikes against the enemy, strikes that continued throughout the war and constituted a major effort of the American-led coalition.

British and Commonwealth surface warships, primarily cruisers and destroyers, also bombarded North Korean coastal installations. One of the ships that did so, HMS Belfast, today remains afloat, moored in the Thames. There, as a museum, it reminds visitors to London of the conflict in Korea, which is now part of Britain’s maritime heritage.

Why did America’s army at first perform so badly?

In 1950 the United States Army was a shell of what it had been five years earlier. As a result of severe budgetary reductions mandated by President Truman and of the mistaken belief promoted by the newly established U.S. Air Force that airplanes with nuclear weapons were now the primary weapons of war, the army’s combat capabilities had become limited. The few troops it had were untrained, and its supplies, particularly ammunition, were inadequate. In Washington, Omar Bradley, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, is reported by David Halberstam to have said at the end of the Korean War that the U.S. Army could not fight its way out of a paper bag. That certainly was the case with Walton Walker’s Eighth Army. Despite efforts on his part to train the men in his command, Walker was unable to produce an army ready for combat. The results were a foregone conclusion. Both the North Koreans and the Chinese easily pushed aside Eighth Army (as well as Ned Almond’s X Corps). Only Walker’s pugnacious defense at Pusan saved his reputation. Yet even that was insufficient for him to retain command. MacArthur and the army brass in Washington were about to relieve General Walker. Only his unexpected death kept them from doing so.

What role did the U.S. Navy play in the Korean War?

Simply stated, a significant one. The American navy ferried troops to and from Korea. It bombarded enemy installations. It transported General MacArthur’s landing force to Inchon, and evacuated 105,000 men of General Almond’s X Corps from Hungnam. It also transported the air force’s F-86 fighter planes that were deployed to Korea. Moreover, U.S. Navy helicopters rescued scores of U.S. airmen who had been shot down.

One role the navy played, however, deserves special mention. This was the continuous series of attacks by naval aircraft against targets in both North and South Korea. From aircraft carriers such as the USS Valley Forge and the USS Boxer operating in the Sea of Japan, F4U Corsairs, AD Skyraiders, and F9F Panthers routinely delivered ordnance to the enemy. But at a not insignificant cost. A total of 564 naval and marine airplanes were lost in combat during the three years of conflict. Of these, sixty-four were Panthers, one of the U.S. Navy’s first jet fighters, which, it must be reported, were outclassed in aerial combat by Russian-built MiG-15s, the aircraft favored by North Korean, Chinese, and Russian pilots.

On one such mission, according to historian Richard P. Hallion, a Panther jet attacked enemy trucks near Wonson, and was sent spinning downward after being hit by flak. The pilot, new to naval aviation, nevertheless regained control of the aircraft although the jet’s right wing then struck a telephone pole. Somehow, the pilot kept his craft in the air. He flew to more friendly territory and ejected from his damaged jet. Soon picked up, the pilot was returned to his carrier. His name was Neil Armstrong.

How well did America’s air force do in the Korean War?

For the United States Air Force, the war in Korea was no small affair. During three years of conflict, it flew 720,000 sorties and lost more than 1,400 aircraft. Moreover, the full array of combat missions were flown. Employing a variety of aircraft, air force pilots flew close air support, interdiction, reconnaissance, strategic bombing, antisubmarine, and air combat missions. Hardly a day went by when the air force was not engaged in the skies above Korea.

The war also brought new developments in air warfare. Helicopters saw their first employment in combat, as did American and Russian jet-powered aircraft. Air-to-air refueling had its wartime introduction. Each of these developments pointed toward the future.

Nearly half the missions flown in Korea were for the purpose of interdiction. This meant the disruption and destruction of enemy supplies and troops well behind the battle line. Having just gained independence from the army, the air force had little interest in focusing on close air support. As strategic bombing targets were limited, the air force concentrated on interdicting the flow of men and matériel. In this, it achieved considerable success. Yet, given the manpower available to the North Koreans and the Chinese, as well as their willingness to accept casualties, interdiction did not achieve its goal of collapsing the enemy’s ability to wage war.

Where the air force performed extremely well was in air-to-air combat against Russian-built MiG-15 fighters. The MiGs were first-rate aircraft. Against them, America’s best fighter, the F-86 Sabre, nevertheless excelled. Sabre pilots claimed the destruction of 792 MiGs, a number now generally accepted as too high. But only seventy-eight Sabres were shot down by MiGs. Success of the F-86s was due largely to their pilots, who were experienced and well trained. Sound tactics and a superior gunsight made the difference as well. Most of the time, MiG pilots were outmatched. A few did well, particularly a number of Russians, but the majority of those who flew from Antung and the other bases in Manchuria crossed the Yalu at their peril. When, in July 1953, an armistice was signed at Panmunjom, one fact was indisputable: above North Korea Sabres owned the sky.

What, other than the invasion in June 1950 by the North Koreans, were the key turning points of the Korean War?

There were several. The first was Walton Walker’s successful defense of the Pusan Perimeter. This meant that Kim Il Sung’s army did not achieve its goal of unifying Korea.

The second turning point was MacArthur’s successful landing at Inchon. This led to the defeat of the North Koreans and, as important, boosted the morale of the American army and of the American public, neither of whom had much to cheer about as U.S. soldiers retreated down the peninsula.

The next turning point, one of the most significant in the entire conflict, was the move north by the Americans across the 38th parallel. For the United States, this military operation changed the purpose of the war, from repulsing the North Koreans’ invasion, to eliminating the regime of Kim Il Sung. Crossing the parallel into North Korea also meant that the Chinese would enter the conflict, thereby changing the nature and outcome of the war.

The Chinese attack of November 1950 constituted the fourth turning point. Chinese involvement led to the defeat in battle of an American army. Their involvement also meant that the U.S. would not unify the peninsula under the rule of Syngman Rhee. Moreover, it ensured that the war would not be limited in duration or in casualties.

The fifth turning point was the dismissal of General MacArthur. The general had overstepped the boundaries of U.S. military field commanders. So Truman’s action was entirely appropriate. Nonetheless, MacArthur’s removal was a shock to the American political system and a reminder to the American military that in the United States, generals (and admirals) do not outrank presidents.

The final turning point of the Korean War was the arrival in Korea of Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway as commander of all ground forces. Ridgway took a dispirited American army and transformed it into an effective combat organization. Under his leadership, the Americans stopped several Chinese offensives, depriving them of control over the entire peninsula, but also advanced north against the Chinese, thus establishing what would become the Demilitarized Zone, close to where the conflict had started, at the 38th Parallel. Rarely has an American commander done a better or more important job. Little wonder then that Matthew Ridgway ranks as one of the country’s most capable military leaders.