England: Political divisions in 1066

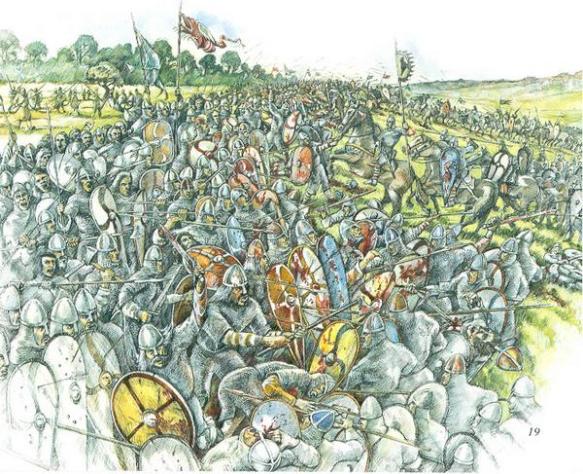

Some of the best evidence of the different military tactics employed by English and Norman armies in 1066 comes from the Bayeux Tapestry. At Hastings, central to the English army’s strategy, as it had been for centuries by then, was the shield wall. Designed to absorb the shock of enemy attacks, this defensive structure was made by men standing closely together in lines with their shields interlocked. The successful deployment of the shield wall and its maintenance in the heat of battle would have required discipline and confidence, and these could only result from training and practice. The Tapestry portrays almost all of the men in the English shield wall wearing mailshirts or hauberks and helmets and carrying kite-shaped shields and spears. They appear to be acting as a coherently organised unit, although perhaps the evidence of the Tapestry should not be interpreted too literally here. Less formally engaged in battle are those mailed and helmeted English infantrymen shown in the Tapestry wielding axes and swords and holding round shields. It has been argued that these weapons were suited to the needs of those fighting in open rather than close order, and that their role in battle was quite different from that of the men in the shield wall.

The Tapestry also shows other elements within the English army. Lightly armed infantry ferociously defend a hillock against a Norman onslaught at one particularly dramatic point in its depiction of the battle. They wear no mail and are bare-headed; most carry spears and small kite-shaped shields, whilst one, with his sword hanging at his side, stands at the foot of the hillock swinging his two-handed axe. There are even suggestions on the Tapestry that the English employed archers at Hastings; certainly, a single bowman stands in front of the shield wall, and, given his position, it can be assumed that he is supposed to be English. Whether he really could be seen as `representative of lines of missile troops who skirmished in front of the heavy infantry before retiring to the rear as the enemy approached’, is more debatable, however. It is equally likely that the single archer is meant to show how few of Harold’s troops had actually turned up by the time the battle began. Nevertheless, it is fair to suggest that large English armies by the late eleventh century were probably made up of several different types of fighting unit, all of which had their own responsibilities on the battlefield. The level of organisation and range of experience required to recruit, deploy and control these armies were formidable, and the speed and extent of the English response to the military demands of 1066 were all the more remarkable given that the kingdom had been largely at peace since 1016. Of course, English armies were not always successful, but the very narrowness of Duke William’s victory at Hastings, coming as it did for the English so soon after Fulford and Stamford Bridge, showed how tough and resilient they could be.

Whether the English ever fought willingly on horseback is another thorny question. In 1055, Earl Ralph of Hereford, Edward the Confessor’s nephew but also a Frenchman, was defeated in battle by Earl Aelfgar and his Welsh ally Gruffudd ap Llewelyn: `before any spear had been thrown’, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records, `the English army fled because they were on horseback’. John of Worcester adds that the English lost because they were ordered to fight on horseback `contrary to custom’. The conventional wisdom, indeed, holds that the English did not use cavalry in battle: they rode to the battlefield, fought on foot and remounted in order either to flee or to pursue a defeated enemy. This is what happened, according to William de Poitiers, when the English arrived at Hastings: `At once dismounting from their horses, they lined up all on foot in a dense formation.’ And there is certainly little to suggest that the horse was seen by the late Anglo-Saxon military élite as anything much more than a sign of status and a means of transport. In this regard the Normans and their French allies were quite different, for troops of heavily armed cavalry were central to their tactics and to their ultimate effectiveness as a fighting force. Together at speed, the specially-bred horse and its rider, mailed and helmeted with a shield in one hand and a spear in the other, constituted an awesomely powerful projectile against which an individual foot soldier would have little chance. On the Tapestry, Harold’s brothers Gyrth and Leofwine are killed by individual mounted warriors. And if groups of these mounted troops operated together (and it is thought that this is how they trained, in units of five or ten known as conrois), the weight of a charge was potentially devastating. One late eleventh-century contemporary, who witnessed French cavalry in operation during the early stages of the First Crusade, thought the charging Frankish knights capable of piercing the walls of Babylon; and it was the shock from this sort of attack which, as the Bayeux Tapestry shows, the English shield wall was intended to absorb. In the end, and with fateful consequences, it was unable to take the strain.

It would probably be wrong to think that the effectiveness of the French cavalry at Hastings was based simply on its weight and its speed, however. If William de Poitiers’s account of the feigned retreats employed by the cavalry during the battle is to be believed, these troops were capable of carrying out difficult and sophisticated manoeuvres which must have required intensive training and regular practice. Despite their obvious importance, though, and despite their prominence in the Tapestry, it would probably also be wrong to think that the heavy cavalry formed the overwhelming bulk of Duke William’s forces during the battle. William de Poitiers places them in the third line of battle, behind the archers and the infantry. There are few depictions of the latter on the Tapestry; but as Duke William lifts his helmet to show his troops that he is still alive, the lower margin of the Tapestry is filled with loosely-clothed, bareheaded bowmen getting into position for what proves to be the decisive phase of the battle. Like the English armies of the eleventh century, therefore, French ones were composed of different kinds of fighting men. Each army at Hastings had its strengths: the English were well-suited to a defensive battle, whilst Duke William’s cavalry allowed him to be more aggressive from the outset, as he needed to be. However, the closeness of the battle should always be borne in mind. Had Duke William rather than King Harold been killed at Hastings, as nearly happened more than once, the Norman invasion would have ended in disastrous failure; and had the English shield wall still stood as darkness gathered on 14 October 1066, William’s chances of becoming king would have been seriously if not completely undermined. However, whilst good fortune contributed to Duke William’s triumph at Hastings, his victory was ultimately attributable to the superiority of the Norman military machine. And if the duchy was not the equal of England in political, economic or cultural terms by 1066, a lucky, determined and superbly able Norman duke had resources at his disposal sufficient to present his English neighbour with an unstoppable military challenge. Indeed, it has been argued that, by the mid eleventh century, the Norman élite `formed the most disciplined, cooperative warrior society in Europe, capable of a communal effort – the conquest and subjugation of England – that was not, and could not have been, mounted by any other European political entity’.