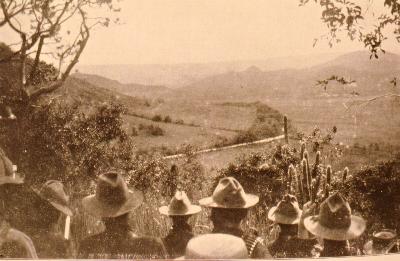

The 3rd Wisconsin awaits orders to charge the Spanish at Coamo.

Puerto Rican and Spanish troops in Guayama.

Puerto Rico was one of only two remaining Spanish possessions in the Western Hemisphere when it became the target of American efforts to rid the Caribbean of Spanish influence in the Spanish-American War. Though the main fighting of the war took place in Cuba, which was secured by 17 July 1898, Puerto Rico seemed a tempting target. The Spanish government here was more liberal than in Cuba, allowing the Puerto Ricans a modicum of self-rule, but the Americans were perceived as liberators who would give the island its independence rather than hold it as a colony.

General Nelson Miles commanded the 3,300 troops who landed on the island on 21 July 1898. Fearing a direct attack on the capital of San Juan would prove too costly, they first captured the port of Ponce. The landings went smoothly, against minimal opposition, and reinforcements were soon on hand. The soldiers began to believe the occupation would be bloodless; the only trouble they had was with street vendors and large numbers of welcoming politicians. After a week of easy duty, Miles ordered his force to move across the island along a number of routes, all heading for San Juan. Only the lack of initiative on the part of the Spanish army kept this from being a bloodbath, because the rugged terrain could easily have disguised any number of ambushes. The most difficult engagement turned out to be no more than a skirmish, resulting in six American wounded and six Spanish deaths.

The Americans methodically made their way across the island, capturing town after town against little or no resistance. There was no battle for San Juan, because word came on 13 August that an armistice had been signed. The capture of Puerto Rico seemed ridiculously easy, but Miles’s multipronged offensive was designed to outflank any large Spanish force, and the Spaniards rarely stood to fight. Though some writers dismissed the attack as a “picnic,” correspondent Richard Harding Davis gave the credit for success to Miles. “The reason the Spanish bull gored our men in Cuba and failed to touch them in Porto Rico [sic] was entirely due to the fact that Miles was an expert matador; so it was hardly fair to the commanding General and the gentlemen under him to send the Porto Rican campaign down into history as a picnic.”

The inhabitants of the island were angry that the United States would not grant them independence. Unlike the situation in Cuba, the United States had made no promise about freeing Puerto Rico. Instead, Congress voted to make the island an “unincorporated territory,” which meant that the Puerto Ricans became citizens of no nation. Wealthy Americans bought up the best lands for agricultural production, and the locals had to work for them. However, there were benefits for the Puerto Ricans. Prior to the U.S. invasion, only two or three improved roads existed on the island, there were no banks, and only about one-fifth of the land was being farmed. U.S. investment and interest improved sanitation, utilities, and roads, though mainly within or between cities, leaving the peasants in the countryside lagging behind. The education system improved until some 80 percent of the island was literate, much higher than most Caribbean countries. Despite this, most of the profits that accrued from the outside investment resulted in those profits leaving the country. By 1930, the United States controlled 50 percent of the sugar production, 80 percent of the tobacco, 60 percent of the banks, 60 percent of the public utilities, and all of the shipping.

In 1917 Congress finally agreed to grant Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship, and in 1947 gave them the right to elect their own governor. To this day, the inhabitants remain divided about the island’s future, roughly equal numbers wanting independence, statehood, or to keep things as they are.